Israel and Palestine 2013

Israel and Palestine 2013

Hardly a day goes by without Israel being in the news, and with its complex political and social issues, as well as its history, I thought it would be an interesting country to visit. There is a perception in Britain that it is a dangerous place, and parts of it are, but if you read up well in advance and keep an eye on developments while you are there the risk is low.

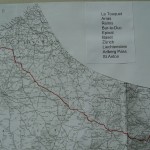

The Foreign Office advises strongly against visiting the Gaza Strip, some areas close to Lebanon, and parts of the West Bank unless you are accompanied by someone with local knowledge. For basic planning I used a large scale National Geographic map and a recent Lonely Planet Guide (LP), which was unusual in having sections on ‘What to do in a rocket attack’, ‘Minefields’ and ‘Gas Masks’. The internet also provided a lot of information, some of which proved to be of dubious accuracy.

There were stories about people having big problems in immigration, being held up for hours, strip searched and having their computers shot to pieces. To some extent this was supported by LP and as a result I did not take my netbook. In the event the immigration officer asked me if I had relatives or knew anyone in Israel, and when I answered “No” to both questions she just said “Welcome to Israel” and waved me through. Israelis I spoke to in the country dismissed the stories as anti-Israel propaganda. Anyway, I made sure I had clean underpants, just in case.

The plan was to stay one night in Tel Aviv, hire a car and work my way round the country for eight days, going to as many interesting places as possible. At the beginning of May the temperature in Tel Aviv was supposed to be in the range 15 to 25°C, which would be quite pleasant after the long cold winter in England. In the event, when the plane landed at 7.30pm it was 38°C (100°F), the normal figure for July and August.

possible. At the beginning of May the temperature in Tel Aviv was supposed to be in the range 15 to 25°C, which would be quite pleasant after the long cold winter in England. In the event, when the plane landed at 7.30pm it was 38°C (100°F), the normal figure for July and August.

Another shock came when the taxi pulled up outside the hotel I had booked on the internet. The address was 42 Allenby Street, one of the main thoroughfares in Tel Aviv, and as we stopped the taxi driver pointed at a boarded up building and said “That is number 42”. Sure enough, amongst the graffiti was a faded plate with 42 on it. For a moment I thought I had fallen for the scam of booking and paying for accommodation that did not exist, but then we saw a sign a few feet away with ‘Sun City Hotel – Entrance round the corner’. After booking in I went along the road to get something to eat (it was 9pm) and decided that it must be quite a safe area, because there were scantily-dressed young ladies on the nearby roundabout enjoying the warm evening.

Burning up in Tel Aviv

The next morning I went out for breakfast and a stroll through a street market before checking out of the hotel. At 10am it was already 36°, with the sun blazing down, and after a short time on the beach I began to feel unwell. The heat was just more than I could take after months of cold weather, and I retreated to a nearby McDonalds for coffee and an ice cream.

Once cooled down I felt better, but the car would not be available for collection until 3pm and I realised that I could not just wander about in the sun. From the map I saw that there was a large shopping mall not too far away, and decided to take refuge there. It was certainly not the way I would have chosen to spend my time in Tel Aviv, but it was a question of survival. At the entrance to the mall was an airport-style security check with a metal detector and a man searching bags. This is routine procedure at shopping malls, railway and bus stations, post offices and most public buildings.

At 2.30pm I arrived at the car hire office in a state of near-exhaustion after walking through the streets with my heavy wheelie case. The car was ready, a white Nissan Micra, which seemed appropriate for touring the Holy Land, as my local vicar has one. His is probably not air-conditioned, but fortunately mine was, and within a short time I was travelling comfortably northwards to my night stop at a tiny coastal resort called Mikhmoret.

Israeli drivers are reputed to be unpredictable and aggressive, but the people who think that have not driven in Albania, Poland or Russia, and I did not find the driving to be too bad.

Mikhmoret turned out to be a village in the sand dunes, and I drove around for miles on sandy tracks before eventually finding my accommodation, which was imaginatively called ‘The Resort’. It was a complex of two-apartment chalets and tents, and the whole atmosphere was very relaxed, with the staff sitting on an open verandah. The man in charge, a South African back-packer type named Mike, showed me to my en-suite room in a chalet and explained that I would be sharing the kitchen with the occupant of the other room. I could not complain about that, because I was not expecting to have a kitchen at all. Mike said I could eat at the Banana Beach Café or get some food from the supermarket not far away. The café was not very inspiring, so I chose the supermarket, and when I got back to the chalet the occupant of the other room was preparing her meal. She was a fairly mature Dutch lady who had once been married to an Israeli and came back to the country every year to work as a volunteer on an agricultural kibbutz. She had found out that Mike and his South African assistant were also volunteers working for the trust that owned ‘The Resort’.

Voluntary work has always been a big thing on kibbutzim (plural of kibbutz), and apparently still is, but to me it didn’t quite seem to fit in with the present day dynamic economy of Israel.

We sat outside to eat, and afterwards Clara made some green tea, consisting of tea bags in glasses of lukewarm water with no milk (or sugar in my case). This confirmed my longstanding view that the Dutch have no idea how to make tea. I have Dutch friends, or at least did have until the subject of tea was raised.

Haifa, Nazareth, Sea of Galilee.

Haifa is only about a 40 minute drive from Mikhmoret and the road enters the town with beaches on the left and modern buildings with the names of high tech companies on the right. Adjacent to the beach were massive free car parks, and as the weather was within the realms of sanity at last I went for a long walk. It was Tuesday, but a very large number of people seemed to have found the time to go to the beach.

Haifa is only about a 40 minute drive from Mikhmoret and the road enters the town with beaches on the left and modern buildings with the names of high tech companies on the right. Adjacent to the beach were massive free car parks, and as the weather was within the realms of sanity at last I went for a long walk. It was Tuesday, but a very large number of people seemed to have found the time to go to the beach.

Back to the car and into the town. The road started to climb. And climb, and climb, and climb, until I suddenly realised that I was climbing Mount Carmel. Near the top I managed to park and look at the view over the harbour and Mediterranean coast to the north. Finding the road out to Nazareth was not easy, but eventually someone told me to keep going downhill until I came to ‘the big road’. My 2012 map showed a squiggly main road to Nazareth, but such is the rate of development in Israel that most of it had been replaced by new super-highways, and it took only a short time to cover the 30 miles.

When I first examined the map it seemed very strange to see what looked like quite ordinary places bearing names such as Nazareth, Jerusalem, Bethlehem and Jerico. Direction signs and place names are usually in Hebrew, Arabic and English, but street names, if they exist, are often only in the local language. Hebrew and Arabic are entirely different but equally impossible to read for anyone with no basic knowledge of the characters. The situation is further confused by the fact that there are often different ways of spelling place names in Roman letters, for example Bethlehem can be Bayt Lahm, and Ashkelon can be Ashqelon.

Most towns are predominantly Jewish or Arab, and it is immediately possible to tell which from the shop signs and other notices. Nazareth is Israel’s largest Arab city and was said to have terrible traffic jams, which certainly turned out to be the case. As soon as I reached the first traffic queue I turned off into a side road and parked, opposite to a big district police station high up on a hill above the city. The LP guide had a tiny map of Nazareth and I set off to find the Old City. The weather had turned hot again and as I walked down the hill I wondered about getting back. A policeman sitting in front of a bar directed me down a steep narrow path which eventually led into a main street, but I could still not see the way to the Old City. I asked another man who insisted in going into a shop and getting me a bottle of water and refused payment for it, before leading me along the road to within sight of my target.

Israel’s largest Arab city and was said to have terrible traffic jams, which certainly turned out to be the case. As soon as I reached the first traffic queue I turned off into a side road and parked, opposite to a big district police station high up on a hill above the city. The LP guide had a tiny map of Nazareth and I set off to find the Old City. The weather had turned hot again and as I walked down the hill I wondered about getting back. A policeman sitting in front of a bar directed me down a steep narrow path which eventually led into a main street, but I could still not see the way to the Old City. I asked another man who insisted in going into a shop and getting me a bottle of water and refused payment for it, before leading me along the road to within sight of my target.

There is no doubt that Jesus and his family did live in Nazareth, but little remains of the fabric of the city of that period. Most of the present day buildings date from the Ottoman-era or later, but the locations of biblical places and events are known to a fair degree of accuracy, and can be explored by following the Jesus Trail and the Gospel Trail.

The Old City is an absolute labyrinth of narrow lanes and alleyways, lined with stalls and shops selling everything from food to souvenirs to electronic goods, in short, the things you find in markets everywhere. Many shops were closed, as I suppose it was not a peak time for tourists. There were passages leading off in all directions, and within a short time I had completely lost my bearings, which the LP says happens to everyone, and should be enjoyed. One stall looked as if it might have maps, and the man gave me a free tourist map of the city, and tried to explain the way to the big police station where I had left the car. He said “If you can’t find it, come back to me and I will take you there in my car”. Very kind, but unfortunately after another five minutes of twists and turns I realised that I had no hope of finding him or the police station.

The Old City is an absolute labyrinth of narrow lanes and alleyways, lined with stalls and shops selling everything from food to souvenirs to electronic goods, in short, the things you find in markets everywhere. Many shops were closed, as I suppose it was not a peak time for tourists. There were passages leading off in all directions, and within a short time I had completely lost my bearings, which the LP says happens to everyone, and should be enjoyed. One stall looked as if it might have maps, and the man gave me a free tourist map of the city, and tried to explain the way to the big police station where I had left the car. He said “If you can’t find it, come back to me and I will take you there in my car”. Very kind, but unfortunately after another five minutes of twists and turns I realised that I had no hope of finding him or the police station.

My boyhood reading included stories of people wandering in labyrinths until they died of starvation or being bitten by a poisonous spider. As I staggered on through passage after passage I was beginning to give up all hope, when I suddenly emerged into a narrow side street to find a police car standing in front of me. The two officers spoke some English and I explained that I could not find the way back to my car, which was parked by a district police station high on a hill. It was not their police station, but they knew where I meant and started to tell me how to get there. After a while I said “I don’t think I can walk that far”. They said “All right, we will take you there!”

On the way one of them asked “Are you Jewish?”, to which I replied “No”. “Are you a Christian?” “Yes”. Afterwards I wondered what would have happened if I had said I was Jewish. Then they asked where I was going, and I said “Tiberias”. One of them said “It will be hotter in Tiberias”. Just what I wanted to hear.

It was. Tiberias is on the Sea of Galilee and at the roadside high above the town was a sign indicating normal sea level, which is about 200m (650ft) above the Galilee shore. The temperature was 42°C (107.4°F) at about 3pm. The hotels were well signposted, and I quickly found one, booked in for two nights and set off to walk to the sea front, which was about one kilometre downhill. By half way I had had enough, and went back to the hotel, intending to try again in the evening, when it might be cooler.

above the Galilee shore. The temperature was 42°C (107.4°F) at about 3pm. The hotels were well signposted, and I quickly found one, booked in for two nights and set off to walk to the sea front, which was about one kilometre downhill. By half way I had had enough, and went back to the hotel, intending to try again in the evening, when it might be cooler.

A strange thought occurred to me. Everyone in Britain knows that you cannot make good tea on the top of a mountain, because the water boils at too low a temperature due to the reduced air pressure. Conversely, therefore, it should be possible to make exceptionally good tea in Tiberias. It would have to be made by a British person, because the locals probably use lukewarm water anyway, like Clara.

With this thought in mind I set off for the town again at 7pm, but gave up again half way and went into a very Jewish restaurant where I managed to eat half of the vast quantity of food put in front of me.

Lebanon, the Golan Heights and Syria

One of the aims of my trip was to visit a car museum at a place called Tel Hai Industrial Park near the Lebanese border, in the extreme north of the country. The Foreign Office warns against going to some areas close to the Lebanese border, because they are disputed territory. As I drove north on highway 90 I expected that the traffic would gradually fall off and there would be less general activity, but that was not the case. Very close to the border is a town called Kiryat Shmona, which seems to be quite a thriving place despite having been the target of rockets from Lebanon from time to time. The neighbouring part of Lebanon is run by Hezbollah, an anti-Israel Muslim group, and the unguided rockets take only 30 – 40 seconds to cross the border. At the very end of the road is a village called Metula, which is actually quite old, but has a lot of new building in progress right up to the border. It is possible to drive up to the border fence, and nearby is a half-buried tank, a memento of a battle in the area. Lebanon looked quite peaceful, without a rocket in sight.

One of the aims of my trip was to visit a car museum at a place called Tel Hai Industrial Park near the Lebanese border, in the extreme north of the country. The Foreign Office warns against going to some areas close to the Lebanese border, because they are disputed territory. As I drove north on highway 90 I expected that the traffic would gradually fall off and there would be less general activity, but that was not the case. Very close to the border is a town called Kiryat Shmona, which seems to be quite a thriving place despite having been the target of rockets from Lebanon from time to time. The neighbouring part of Lebanon is run by Hezbollah, an anti-Israel Muslim group, and the unguided rockets take only 30 – 40 seconds to cross the border. At the very end of the road is a village called Metula, which is actually quite old, but has a lot of new building in progress right up to the border. It is possible to drive up to the border fence, and nearby is a half-buried tank, a memento of a battle in the area. Lebanon looked quite peaceful, without a rocket in sight.

Tel Hai, once a kibbutz I believe, is a very modern industrial estate with massive buildings carrying the names of high tech companies, but the man in the gatehouse informed me that the car museum had been moved to another site a long way away about five years ago.

From here I took the road straight across the Golan Heights towards the border with Syria. Within a short time there were wire fences both sides of the road with notices in the usual three languages stating DANGER, MINES. Despite this, hiking in the Golan Heights is a very popular activity, and is said to be quite safe as long as you stay on the marked tracks. The Golan Heights were more mountainous than I expected, and the scenery was very good.

From here I took the road straight across the Golan Heights towards the border with Syria. Within a short time there were wire fences both sides of the road with notices in the usual three languages stating DANGER, MINES. Despite this, hiking in the Golan Heights is a very popular activity, and is said to be quite safe as long as you stay on the marked tracks. The Golan Heights were more mountainous than I expected, and the scenery was very good.

A few miles before the Syrian border I turned north towards Mount Hermon and Israel’s only ski resort. From a distance traces of snow were still visible near the summit, which is actually in Syria. On the way I came to a busy little town called Majdal Shams, which is the commercial and cultural centre of the Golan Druze community. The Druze are a minority Arabic language group who practice a version of Islam, and are mainly resident in Lebanon and Syria.

The ski resort is a few miles north of Majdal Shams, and in May is definitely out of season, with just a few people there servicing machinery, although it is a hiking base in the summer. As I walked back to the car after a wander round I noticed that one of the rear tyres appeared to have low pressure, and found a small tyre shop in the main street of Majdal Shams on the way through. No one in the business spoke English, but a man who did was fetched from somewhere nearby and the tyre problem was quickly resolved, with a refusal to accept payment. I must be one of the few British people who can boast of having been to a Druze tyre shop.

The ski resort is a few miles north of Majdal Shams, and in May is definitely out of season, with just a few people there servicing machinery, although it is a hiking base in the summer. As I walked back to the car after a wander round I noticed that one of the rear tyres appeared to have low pressure, and found a small tyre shop in the main street of Majdal Shams on the way through. No one in the business spoke English, but a man who did was fetched from somewhere nearby and the tyre problem was quickly resolved, with a refusal to accept payment. I must be one of the few British people who can boast of having been to a Druze tyre shop.

From Majdal Shams the road runs south roughly parallel to the Syrian border, and I knew that at one point it was very close. A layby with a snack bar suddenly appeared at the roadside and when I stopped for coffee I realised that this was a viewpoint for Syria. The border fence could be seen running through the valley below, with watchtowers and a cluster of white buildings. A coach pulled into the layby and disgorged its passengers, who sat in front of their guide as she explained the features of the view in a language that I could not understand. Another coach came, full of Americans, who started asking their guide questions, some of which I think he did not want to hear.

Further along the layby was a pillar with buttons marked HE and EN. Pressing the EN button produced a commentary from a lady with an American voice, describing the view and extolling the performance of the Israeli forces in capturing the Golan Heights from Syria in 1967 and defending them in 1973. The white buildings are the permanent base of the UN Disengagement Observer Force (Undof), and alongside them through my binoculars I could see the ruins of the Syrian town of Quneitra, totally destroyed in 1973 and deliberately not rebuilt by Syria. As I stood on the layby two Israeli military convoys went past, as well as a few UN vehicles.

American voice, describing the view and extolling the performance of the Israeli forces in capturing the Golan Heights from Syria in 1967 and defending them in 1973. The white buildings are the permanent base of the UN Disengagement Observer Force (Undof), and alongside them through my binoculars I could see the ruins of the Syrian town of Quneitra, totally destroyed in 1973 and deliberately not rebuilt by Syria. As I stood on the layby two Israeli military convoys went past, as well as a few UN vehicles.

It seemed slightly surprising, but the viewpoint is actually on an extinct volcano, one of two in the area, and just along the road a local kibbutz has produced an educational display in a disused quarry showing the structure and working of the volcanos.

On the way back to Tiberias I drove round the eastern and southern sides of Gallilee before stopping in the town to have a proper look at it, as I had failed to do the previous day. LP described it as tacky, but I have been to worse places. One item of interest was the Water Level Indicator on the promenade with a digital display built into a frame shaped like the lake. A great deal of importance is attached to the water level, because the lake provides a quarter of Israel’s water supply, and if the level is too low the quality is compromised, and if it is too high there is a danger of flooding.

The next morning I set off for Jerusalem, and the most direct route was via highways 90 and 1, which run partly through the West Bank. My car was not insured for general use in the West Bank, but there is an exception for these two roads, because they are under control of the Israeli military police.

Some distance south of Galilee highway 90 runs past Beit She’an, which has the dubious distinction of holding the record for the highest temperature ever recorded in the whole of Asia, at 53.9°C (129°F). Luckily I hit it on a cool day – it was only about 38°C. The road enters the West Bank a few miles past Beit She’an with a military checkpoint and runs for a long way quite close to the Jordan river, with the hills of Jordan clearly visible the other side.

Some distance south of Galilee highway 90 runs past Beit She’an, which has the dubious distinction of holding the record for the highest temperature ever recorded in the whole of Asia, at 53.9°C (129°F). Luckily I hit it on a cool day – it was only about 38°C. The road enters the West Bank a few miles past Beit She’an with a military checkpoint and runs for a long way quite close to the Jordan river, with the hills of Jordan clearly visible the other side.

Jerusalem, Bethlehem, Jerico

Shortly before turning westwards towards Jerusalem the road passes within three miles of Jerico, which I particularly wanted to visit, but I had been told not to take any ‘small roads’, so that would have to wait until later.

My hotel was in the centre of the modern part of Jerusalem, the other side of the Old City, and I was expecting to have a nightmare drive, especially as I did not have a decent map. On highway 1 at the entrance to Jerusalem was a toll-booth style military checkpoint but after that I seemed to have an easy run and found a free parking space near the central bus station, where I hoped to get a good map to enable me to find the hotel.

Within a short time of entering the bus station I was caught by a taxi driver, who insisted that he had the map I needed, and to cut a long and miserable story short, I finished up paying the equivalent of £6 for a tatty old map to get rid of him. However, the map did enable me to get to the hotel without too much trouble.

The modern Jerusalem Gardens Hotel had free undercover parking and a panoramic view from the balcony of my 11th floor room. The Old City was about two miles away, with a direct tram service from close to the hotel. Like all the non-locals, I had difficulty in getting a ticket from the machine, until a young American and his Canadian girlfriend came to my aid. My ten shekel coin would not work, so he bought a ticket with his money and refused to accept payment. He was wearing a T-shirt and shorts and a mini-kippa, a tiny skull cap about three inches in diameter favoured by many young Jewish men, and by the time we had gone six stops I knew his whole life story. His parents had moved to Israel some time ago and he had been studying at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem but was now engaged in religious studies elsewhere. He was a real all-American boy from Boston and it somehow seemed difficult to imagine where he would fit into the serious religious community in Israel, but I am far from an expert on such matters.

about two miles away, with a direct tram service from close to the hotel. Like all the non-locals, I had difficulty in getting a ticket from the machine, until a young American and his Canadian girlfriend came to my aid. My ten shekel coin would not work, so he bought a ticket with his money and refused to accept payment. He was wearing a T-shirt and shorts and a mini-kippa, a tiny skull cap about three inches in diameter favoured by many young Jewish men, and by the time we had gone six stops I knew his whole life story. His parents had moved to Israel some time ago and he had been studying at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem but was now engaged in religious studies elsewhere. He was a real all-American boy from Boston and it somehow seemed difficult to imagine where he would fit into the serious religious community in Israel, but I am far from an expert on such matters.

As mentioned earlier, my car was not insured for use in the West Bank (Palestine), which meant that I could not go to Bethlehem or Jerico in it. Getting there by public transport is not easy unless you have a lot of time and most guide books suggest going by taxi, which would be very expensive. The young American had advised me against getting involved with Jerusalem taxi drivers, backing up my own experience, and I decided that it would be cheaper and more convenient to hire a car for a day from an Arab company for use in the West Bank. A company recommended in the guide books was Green Peace (nothing to do with Greenpeace) in East Jerusalem, just north of the Old City, and I thought I would call in to their office while I was in the area. The tram stopped on the edge of East Jerusalem and I asked some people in a travel agency for the way to the Green Peace office. They rang Green Peace, who said they would have a car available for me at 8am the next morning.

The temperature here was tolerable and I set off to explore the old city, starting at Damascus Gate. In many respects it was similar to the old city in Nazareth, but larger and with much more activity. It had the same maze of lanes and alleys, but the main ones were longer and straighter, mostly with names so that I could locate them on my map. There are many churches, synagogues and other notable buildings but it is difficult to see them from ground level because they are so densely packed in with little space between them. I particularly wanted to see the Western Wall and the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, but it was getting late in the day so I decided to come back when I had more time.

The temperature here was tolerable and I set off to explore the old city, starting at Damascus Gate. In many respects it was similar to the old city in Nazareth, but larger and with much more activity. It had the same maze of lanes and alleys, but the main ones were longer and straighter, mostly with names so that I could locate them on my map. There are many churches, synagogues and other notable buildings but it is difficult to see them from ground level because they are so densely packed in with little space between them. I particularly wanted to see the Western Wall and the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, but it was getting late in the day so I decided to come back when I had more time.

In central Jerusalem soldiers, male and female, were everywhere, many of them carrying automatic rifles. At one point, near the bus station, there were so many that I was practically swept along by them and thought for a moment that I had been conscripted into the Israeli Defence Force.

The next morning (Friday) I got up at 6.30am and caught a tram to East Jerusalem, arriving at Green Peace just after 8.00. As promised a car was ready, a silver Kia Rio with Israeli yellow number plates as opposed to the green number plates (actually white at the front and green at the back) for cars registered in the West Bank. The whole issue of driving in the West Bank is very confusing, because if you are in the wrong place with the wrong car at the wrong time you can find yourself being stoned by angry locals. When I told the Green Peace man what I was proposing to do he said “You can go anywhere in this car”. It had a big label on each side with Jerusalem Car Rental and a picture of a white dove, but whether that carried any weight I do not know. It just made me feel like somebody from the UN.

ready, a silver Kia Rio with Israeli yellow number plates as opposed to the green number plates (actually white at the front and green at the back) for cars registered in the West Bank. The whole issue of driving in the West Bank is very confusing, because if you are in the wrong place with the wrong car at the wrong time you can find yourself being stoned by angry locals. When I told the Green Peace man what I was proposing to do he said “You can go anywhere in this car”. It had a big label on each side with Jerusalem Car Rental and a picture of a white dove, but whether that carried any weight I do not know. It just made me feel like somebody from the UN.

So I set off for Bethlehem. It is a very short distance, about 6 miles, and well-signposted, but I got confused about the entrance through the Separation Wall, and when I turned round I was accosted by a taxi driver who wanted to be my guide. After shaking him off I joined the queue for the check point. The Separation Wall, which has been built along much of the boundary of the West Bank, is enormous and hideous. It is about 8 metres high (26ft) and brought back memories of the Berlin Wall, but rather than preventing people from going through it is intended to prevent them from bringing weapons into Israel.

After a brief check I emerged into Bethlehem, to find a man standing in the road in front of me. He said “I am a guide. You are not in Israel now, you are in Palestine. It is different here. You need a guide.” I insisted that I did not need a guide and drove away. Unfortunately the street in front was no entry, so I had to make a loop through side roads and came back on to the original street about a hundred yards further along, where my friendly guide was standing in front of me again. I drove past him and found myself facing one of the most uninviting streetscapes I have ever seen anywhere. Welcome to Bethlehem. My first reaction was to turn round and go straight back, but I persevered and the scene improved to the point where it was only grim.

Closer to the city centre it was better and I quickly found a place to park near a police station within about fifty yards of Manger Square, which presented a much more appealing image. The square is in between the Church of the Nativity and the entrance to the Old City, and is lined with cafés and shops.

Closer to the city centre it was better and I quickly found a place to park near a police station within about fifty yards of Manger Square, which presented a much more appealing image. The square is in between the Church of the Nativity and the entrance to the Old City, and is lined with cafés and shops.

It was still early in the day and the queue for the Church of the Nativity was short, so I joined it and went through the security check and the Door of Humility, an arch so low that even I had to crouch down to get through. Once a much higher opening, it was reduced by the Crusaders to prevent attackers from riding in on horseback. A service was in progress and I found myself at the back of a large crowd, ushered into an area on one side of the nave. The area in which the service was being held was extremely beautiful.

As far as I could tell it was going to be a very long time before there was an opportunity to venture any further into the church, and I was not religious enough to wait, so I crawled back through the door and went across the square into the Old City.

religious enough to wait, so I crawled back through the door and went across the square into the Old City.

Bethlehem Old City is smaller and more open than those in Nazareth and Jerusalem, with wider cobbled or paved streets used by vehicles, although there are alleyways branching off. On the way back to the car I passed the police station, where some tourists were photographing a policeman standing in the doorway with a rifle. This was what I regard as a proper rifle, not the stubby automatic weapons that the army and police seemed to have everywhere else. Normally it is unwise to photograph police or army personnel, but I asked if I could take a photograph and he said I could.

Bethlehem Old City is smaller and more open than those in Nazareth and Jerusalem, with wider cobbled or paved streets used by vehicles, although there are alleyways branching off. On the way back to the car I passed the police station, where some tourists were photographing a policeman standing in the doorway with a rifle. This was what I regard as a proper rifle, not the stubby automatic weapons that the army and police seemed to have everywhere else. Normally it is unwise to photograph police or army personnel, but I asked if I could take a photograph and he said I could.

The route back to the checkpoint was more presentable than the way in, but approached from this direction the Separation Wall was even more forbidding. Shortly before the gate was a section of the wall covered with graffiti, some of it by well-known people, including Banksy, expressing support for the Palestinian cause. There were only two or three vehicles in front of me at the checkpoint, but it took several minutes to get through. I was asked if there was anything in the boot of the car, to which I said I didn’t think so (I hadn’t looked), but was then just waved through.

forbidding. Shortly before the gate was a section of the wall covered with graffiti, some of it by well-known people, including Banksy, expressing support for the Palestinian cause. There were only two or three vehicles in front of me at the checkpoint, but it took several minutes to get through. I was asked if there was anything in the boot of the car, to which I said I didn’t think so (I hadn’t looked), but was then just waved through.

On to Jerico via Jerusalem. Jerico is about 25 miles from Jerusalem, via highway 1, and shortly after entering the West Bank I turned off the main road, through another checkpoint and up the hill to get some fuel at a filling station on the outskirts of Ma’ale Adumim, the largest of the notorious settler towns. Many countries, but not Israel, consider that these towns on captured territory are illegal under international law, but more houses are being built in the West Bank all the time. They are often occupied by ultra-orthodox Jews and the whole subject is extremely contentious.

Because of time pressure I went straight back to Highway 1 and on to Jerico, which is very much a desert town. My map showed all the roads into Jerico as unpaved tracks, and I am sure some still are, but the route signposted was a well surfaced but dusty single carriageway road. After a short distance was a check point with a big sign at the side of the road in English stating that this was the point of entry to Palestine Area A, and it was illegal and dangerous for Israeli citizens to proceed any further. I was waved through without stopping.

Because of time pressure I went straight back to Highway 1 and on to Jerico, which is very much a desert town. My map showed all the roads into Jerico as unpaved tracks, and I am sure some still are, but the route signposted was a well surfaced but dusty single carriageway road. After a short distance was a check point with a big sign at the side of the road in English stating that this was the point of entry to Palestine Area A, and it was illegal and dangerous for Israeli citizens to proceed any further. I was waved through without stopping.

Another complicated political issue. The West Bank is divided up into three areas, A, B and C, defining the amount of civil and military power Israelis and Palestinians have in each. These are not single large areas, but types of area. Area A is under full Palestine Authority civil and military control, and covers most cities in the West Bank, including Bethlehem and Jerico. Area B is under Palestinian civil control but Israeli military control, and Area C (including highways 1 and 90 in the West Bank) is under full Israeli control. As it said on the sign, Israeli citizens are forbidden to enter any part of Area A, but with a British passport I could. Strange, but true.

At the boundary of Jerico was a Palestinian military check point, and behind it another big notice stating that the development taking place on the area of land ahead was a gift from the American people to the Palestinian people. It was a vast site, partly built up, including a new chain hotel.

At first I seemed to have the only car with Israeli yellow numbers, which made me slightly uncomfortable, but then I did see a few others. It was easy to park and when I went for a walk around no one took any notice of me, and I was not hassled in any way. It struck me as quite a pleasant town, with mainly mid-twentieth century buildings rather than the ancient ones that might be expected. Maybe it was slightly less prosperous than Israeli Arab towns like Nazareth, but I did not see any great signs of poverty.

easy to park and when I went for a walk around no one took any notice of me, and I was not hassled in any way. It struck me as quite a pleasant town, with mainly mid-twentieth century buildings rather than the ancient ones that might be expected. Maybe it was slightly less prosperous than Israeli Arab towns like Nazareth, but I did not see any great signs of poverty.

Joshua and his trumpet did a good job, as there was no trace of the old city walls, but in any case they would have fallen down by now due to the incessant horn-blowing by local drivers.

Back in Jerusalem I handed the car to Green Peace unscathed and walked down to the Old City. It was impossible to get in against the vast tide of people coming out of Damascus Gate, so I went round to New Gate and right through to the Western Wall (Wailing Wall) in the far corner of the City. At one time, when the City was in Arab hands, the Wall was alongside a narrow alley behind a line of houses, but when the Israelis gained control they demolished the houses and created a large open space in front of it. Access to this area is via a security check where my backpack was X-rayed.

Back in Jerusalem I handed the car to Green Peace unscathed and walked down to the Old City. It was impossible to get in against the vast tide of people coming out of Damascus Gate, so I went round to New Gate and right through to the Western Wall (Wailing Wall) in the far corner of the City. At one time, when the City was in Arab hands, the Wall was alongside a narrow alley behind a line of houses, but when the Israelis gained control they demolished the houses and created a large open space in front of it. Access to this area is via a security check where my backpack was X-rayed.

Until quite recently only men were allowed to go up to the Wall, but part of it, probably about one third, is now reserved for women. There is great resentment about this on the part of some ultra-orthodox Jews, and a few days after my visit hard liners started throwing things at the women worshippers, leading to a clash with the police. There are other examples of segregation, such as the bookshop on one side of the square which has separate entrances for men and women. Adjacent to the men’s area of the wall is a door into a building where large numbers of men, many in orthodox dress, were engaged in prayer, study or earnest discussion. Male tourists are allowed in, but are expected to be modestly attired and have some form of head covering. A baseball cap is quite acceptable for non-Jews, but a benevolent-looking man who appeared to be in charge was raising his eyebrows at some people who did not quite meet the expected standards.

It did not mean a great deal to me, but I was aware that to some of the people present touching the Western Wall was the greatest moment of their lives.

The Dome of the Rock and Temple Mount were clearly visible from the walkway above the Western Wall plaza, but unfortunately there is no access to them on Fridays, which happened to be the day I was there.

to them on Fridays, which happened to be the day I was there.

Next stop was the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, which is one of the many buildings hidden within the streets of the Old City and only properly visible from above. It was actually quite difficult to find the entrance, but once inside and through the security check it was obvious that a great many people had found the way in. The church is believed to be the site of Calvary, where Jesus was crucified and rose from the dead. Inside it are several chapels and the Holy Sepulchre itself, which was at the centre of a large mass of people queuing to get a glimpse of Jesus’s tomb. As might be expected there were many clerics around, but the scene was not enhanced by the considerable number of police officers and soldiers with guns. In the street outside were people selling nicely made wooden crosses about five feet high, and they were finding plenty of customers.

As mentioned above, it was Friday, and approaching the start of the Jewish Sabbeth, or Shabbat, which officially runs from sundown on Friday to sundown on Saturday. Almost everything in the Jewish parts of Jerusalem shuts down completely , starting from about 4pm, and I was lucky to get the last tram but one back to the city centre. The alternative would have been a dreaded taxi, if I could find one, or walking two miles along Jaffa Road, which connects the old and new cities.

By the time the tram reached the city centre the bus station mall and most other shops were closed. People were rushing to get home, many of them quite excited, and the atmosphere was rather like 6pm on a working Christmas Eve in England, but here it happens every Friday. A man in Orthodox dress pushing a pram with a baby in it turned to me as he passed and said “Are you Jewish?” I replied “No”, and he said “Well, Happy Shabbat anyway!”.

Happy Shabbat? For me it looked more like Hungry Shabbat, because all the restaurants were closed, and I was not sure whether the hotel would be doing meals. There were still a couple of small shops open selling comfort foods, and I bought a survival pack of biscuits, crisps and nuts, etc., just in case. In fact, the hotel restaurant was in operation so I finished up with a really good meal and a lot of stuff to put in the car.

The view from my balcony on Saturday was unbelievable. In place of the frantic activity on Friday morning there was almost nothing moving. No trams, few cars, few people, no buses running but dozens lined up in neat rows in the car parks below. It was time for me to check out and set off for the Dead Sea, the Negev Desert, and Eilat on the Red Sea.

The view from my balcony on Saturday was unbelievable. In place of the frantic activity on Friday morning there was almost nothing moving. No trams, few cars, few people, no buses running but dozens lined up in neat rows in the car parks below. It was time for me to check out and set off for the Dead Sea, the Negev Desert, and Eilat on the Red Sea.

The Dead Sea, the Red Sea and Eilat

The way out of Jerusalem was the way I had come in, which I had memorized carefully, and with the minimal traffic on Shabbat I expected it to be easy. But as I found on my travels many times before, nothing is easy. The route from the city centre ran along a main road called Bar Ilan Street, which was easy to find, but closed with barriers on Shabbat because it was an Orthodox Jewish neighbourhood. There is strong feeling about people driving through such areas on Shabbat, so I had to find an alternative route that would take me well clear of the closed road, which took some time.

Eventually I passed through the checkpoint on to Highway 1, the route I had taken the previous day to Jerico. This time I turned south on to

highway 90, through another checkpoint and within a short time the Dead Sea appeared on the left with the hills of Jordan on the opposite bank a few miles away. After about twenty miles the West Bank finished (yet another checkpoint) and the Dead Sea resort of Ein Gedi came into view. Ein Gedi has a public beach with free parking, a lifeguard station, toilets and few other facilities. At the entrance was a big notice telling people what they should and should not do on the sea shore.

highway 90, through another checkpoint and within a short time the Dead Sea appeared on the left with the hills of Jordan on the opposite bank a few miles away. After about twenty miles the West Bank finished (yet another checkpoint) and the Dead Sea resort of Ein Gedi came into view. Ein Gedi has a public beach with free parking, a lifeguard station, toilets and few other facilities. At the entrance was a big notice telling people what they should and should not do on the sea shore.

Amongst the things you should not do are jump into the water, swim, swallow the water, get it on your face or in your eyes. The procedure for entering the water is to do so by gently lowering yourself backwards into it, until you are floating on your back, as many people were doing. If you do swallow the water or get it in your eyes you have to seek immediate medical attention from the lifeguard station. I put my hand in the water and tasted it, and it was incredibly saline. It actually has a mineral content of about 33%, mainly salt, but also magnesium, iodine and bromine. Within a short time my lips began to sting and I had to wash them with fresh water that I had in the car.

Some people were covering themselves with black mud, which is supposed to be good for the skin. I would have thought that this would intensify the effect of the sun’s radiation, leading to burning, but in fact the sun’s strength is reduced due to the dense atmosphere. The Dead Sea shore is the lowest point on earth, at about 425m (1380ft) below normal sea level, so the tea there should be fantastic if properly made. According to the digital indicator on the lifeguard station the temperature was 40°C (104°F).

Just off the main road few miles south of Ein Gedi is a string of expensive spa hotels right on the beach, designed to enable people to get the maximum health benefit from the water. More beaches and hotels are to be found on the separate, smaller part of the Dead Sea to the south, and at the very end is the Dead Sea Works, a massive, rusting industrial complex built in1930 to extract minerals, particularly potash, salt and magnesium.

From this point to Eilat and the Red Sea was a straight, boring drive of about 100 miles along the edge of the Negev desert, with the hills of Jordan still clearly in sight on the left. All the books said petrol stations were few and far between in the desert, but on highway 90 they were every 30 – 40 miles.

At 3.00pm I arrived in Eilat and quickly found a hotel, the Aviv B + B. Eilat is a popular holiday destination for Europeans, and most visitors arrive by air. The airport is unusual in that the runway extends right into the middle of the town and the main entrance is directly off the pavement near a roundabout in the town centre. By standing on a grass bank on the roundabout it is possible to get a pilot’s view of the runway.

by air. The airport is unusual in that the runway extends right into the middle of the town and the main entrance is directly off the pavement near a roundabout in the town centre. By standing on a grass bank on the roundabout it is possible to get a pilot’s view of the runway.

It was still Shabbat and I was still hungry. The restaurants in the town were closed, but I thought perhaps there would be some places open on the beach, and there were. The temperature was in the upper 30s, but I was beginning to get used to it, and after the meal I managed to walk the whole length of the promenade by the Red Sea. The sea is not actually red, but is noted for its clear water and the luxuriant plant life on the sea bed. Glass-bottomed boat trips are a big attraction, and the area is popular with scuba divers.

The main item on the BBC World Service the next morning was that Israel had bombed Damascus in a fairly big way. I went down to the reception and asked the way to the breakfast room, only to be told “There isn’t one. We only do breakfast in the winter”. So although the sign with Aviv B + B could be read from almost all over the town it was really just the Aviv B. They recommended a nearby bakery for breakfast, where I paid a small fortune for coffee and a bagel. Some idea of the usual clientele of Eilat can be obtained from the fact that round the corner from the Aviv B was a place called the Fawlty Towers Hostel, with pictures of Basil, Sybil, Polly and Manuel on the sign.

and asked the way to the breakfast room, only to be told “There isn’t one. We only do breakfast in the winter”. So although the sign with Aviv B + B could be read from almost all over the town it was really just the Aviv B. They recommended a nearby bakery for breakfast, where I paid a small fortune for coffee and a bagel. Some idea of the usual clientele of Eilat can be obtained from the fact that round the corner from the Aviv B was a place called the Fawlty Towers Hostel, with pictures of Basil, Sybil, Polly and Manuel on the sign.

Unless you go through into Jordan or Egypt the choice of roads from Eilat is limited to two, as the town is, in effect, on a land-locked peninsular. This meant either retracing my route for some distance or driving along the Egyptian border, a road that was closed at the time of publication of my LP guide (July 2012) due to terrorist incursions leading to the deaths of a number of civilians. The English lady who owned the Aviv B said the road was open again, but it squiggled about in the mountains and was “even more boring than the other one”.

The Egyptian Border, Negev Desert, and Be’er Sheva

The Egyptian border road, Route 12, was far more scenic and interesting than the “other one”, and I realised that the lady’s measure of boring was related to the number of places where food and drink were available (none the way I was going). The only other vehicles on the road were taxis going the other way, although I don’t know where they were coming from, because it was a long way from anywhere.

The Egyptian border road, Route 12, was far more scenic and interesting than the “other one”, and I realised that the lady’s measure of boring was related to the number of places where food and drink were available (none the way I was going). The only other vehicles on the road were taxis going the other way, although I don’t know where they were coming from, because it was a long way from anywhere.

After a few miles the road came to the border fence with Egypt and a proper Israeli army checkpoint, with camouflage and a big gun on the road pointing towards Egypt. There seemed to be two young men and two young women soldiers, and when I held up my passport one of the men asked me where I was from. I said “England” and he replied “Have a good day”.

The border fence was new and quite impressive, consisting of a double wire fence with a gap in between, and was slightly reminiscent of the pictures of the Great Wall of China as it stretched away into the distance, following the contours of the land.

pictures of the Great Wall of China as it stretched away into the distance, following the contours of the land.

Eventually another check point came into view, near the point where Highway 12 branched away from the border, to leave Highway 10 continuing about 120 miles to the coast and Gaza Strip. The soldier in charge just waved me through with a broad grin, and I had a feeling that he knew I was coming. If you broke down on that road I don’t think there would be any need to fetch Green Flag, the Israeli Defence Force would coming looking for you.

At the junction with Highway 40, the route used by normal people travelling north from Eilat, is a proper oasis, with a small shop and restaurant surrounded by trees. In the middle the actual spring had been made into a small water feature. About a dozen cars  were parked there, most if not all, travelling on Highway 40.

were parked there, most if not all, travelling on Highway 40.

My night stop was to be Be’er Sheva (Beersheba), a drive of about another 100 miles across the desert, which was very barren but with some good mountain backdrops and occasional signs warning of camels on the road, although I did not see any. Army exercises were taking place here and there on both sides of the road.

Shortly before a small town called Mitspe Ramon the scenery became quite spectacular as the road crossed a vast crater called Makhtesh Ramon, which the LP likens to the Grand Canyon, although I would say that is a bit of an exaggeration. It is nevertheless an extraordinary landscape, with multi-coloured rock formations, and could be on another planet. The crater is 8km wide and 40km long, Mitspe Ramon being perched high on a cliff above it with a lookout built out over a sheer drop to enable visitors to make the most of the view.

40km long, Mitspe Ramon being perched high on a cliff above it with a lookout built out over a sheer drop to enable visitors to make the most of the view.

At the roadside on the approach to Be’er Sheva were a number of Bedouin encampments in which people appeared to be living in appalling conditions, in what looked like makeshift tents, huts and old vehicles. Some Israelis told me that what  can be seen from main road is just a drop in the ocean compared with the amount that is out of sight. Some Bedouin still live the nomadic lifestyle in tents, moving around in the desert and others have become fully urbanised.

can be seen from main road is just a drop in the ocean compared with the amount that is out of sight. Some Bedouin still live the nomadic lifestyle in tents, moving around in the desert and others have become fully urbanised.

Not far from Be’er Sheva is a Bedouin city called Rabat with a population of 40,000 and a reputation for being crippled by poverty and crime. LP said a visit was not to be recommended.

According to LP accommodation in Be’er Sheva was limited to a choice between an expensive hotel and rooms in a college residential building used mainly by students and visiting professors. As well as being cheaper I thought the college would be more interesting. It proved to be very Jewish, with absolutely everything in Hebrew, although most of the staff spoke English. The accommodation was basic, but far better than the hall of residence I lived in as a student in London in the late1950s, and the room was more comfortable for reading or studying than any hotel room I have experienced.

Be’er Sheva is quite a pleasant town, actually very old, but without much ancient fabric as far as I could see. The so-called Old City does not have a lot of character and is supplemented by a fair-sized modern shopping mall, but one thing I wanted to see was the Bedouin Market, which I thought might provide an insight into their lifestyle and culture.

Be’er Sheva is quite a pleasant town, actually very old, but without much ancient fabric as far as I could see. The so-called Old City does not have a lot of character and is supplemented by a fair-sized modern shopping mall, but one thing I wanted to see was the Bedouin Market, which I thought might provide an insight into their lifestyle and culture.

At breakfast the next morning I was told off for sitting in the wrong place in the vast and almost empty restaurant, and the lady in charge treated the ‘guests’ as if they were 19-year-old students who were clearly up to no good and needed to be put in their place. I quite enjoyed the experience.

The Bedouin Market was a great disappointment. After stretching my walking ability to its limit it turned out that the people and the things they were selling were just like those in my local market at home. Most of the stall holders were shouting in the usual manner, but a couple had small loudspeakers playing a recorded message listing the items on offer. So much for tradition.

Ashkelon and Ashdod

From Be’er Sheva I was aiming for the Mediterranean coast for the last night before returning home. On the coast just north of the Gaza Strip are two towns called Ashkelon and Ashdod, both of which escaped a mention in the LP guide, although Ashdod is the fifth largest city in Israel. Looking at the map I somehow got the impression that they were run down places, but in Be’er Sheva I asked a lady who by chance came from that area and she said they were both nice towns.

two towns called Ashkelon and Ashdod, both of which escaped a mention in the LP guide, although Ashdod is the fifth largest city in Israel. Looking at the map I somehow got the impression that they were run down places, but in Be’er Sheva I asked a lady who by chance came from that area and she said they were both nice towns.

The road from Be’er Sheva to Ashkelon runs within a mile of the Gaza Strip and about five miles from Gaza City itself. The Foreign Office warns against getting too close to the Gaza Strip because of rocket attacks, but it was not until I got home that I discovered that in 2012 over 2000 rockets were fired from Gaza into Israel, resulting in some deaths. Due to negotiations with Hamas, the group that controls Gaza, the number so far in 2013 was greatly reduced. Ashkelon and Ashdod were both well within range of the rockets.

At the point nearest to Gaza it appeared that a new educational establishment had been built, and on the bright, clear day that I was there it was hard to believe that there were hostile forces so close. Approaching Ashkelon from the south I came to a massive industrial estate, with enormous trucks running around loaded with materials rather than the ladies-underpants-from-China sort of industry that we have in England nowadays.

Ashkelon itself was a hive of activity with new building going on everywhere, reminding me of a typical fast-growing Florida coastal town. If the people firing the rockets think they are going to intimidate the Israelis they are very much mistaken.

Ashkelon might have a beach and a marina, but as far as I could see the only hotel was the expensive Holiday Inn, so I pushed on to neighbouring Ashdod, a considerably bigger town. At the far end of the long promenade was a large new and very smart hotel, with a couple of older ones nearby. The Hotel Orly had the character of a late 19th century French establish-ment and was the kind of place I was looking for.

After getting sorted I went into the town, which appeared to be quite European as I strolled along a wide boulevard lined with shops and restaurants, but, as in Ashkelon, virtually everything seemed to be in Hebrew At a junction I turned down a side turning, went into a shop at the back of a small precinct, and was surprised to find the shopkeeper talking to a customer in Russian. I did not think much about it then, but a few minutes later as I was sitting in front of a snack bar enjoying a glass of freshly squeezed orange juice I looked around and realised. This was Russia! It was all there, the austere blocks of flats, concrete buildings with the aerials on top, and shabby little precincts. You could have picked the whole lot up and dumped it down in the suburbs of Moscow and no one there would have noticed. In general, however, the lady in Be’er Sheva was right, Ashkelon and Ashdod are nice seaside towns, but they are not likely to be in the European package holiday brochures while there is still the occasional rocket attack.

After getting sorted I went into the town, which appeared to be quite European as I strolled along a wide boulevard lined with shops and restaurants, but, as in Ashkelon, virtually everything seemed to be in Hebrew At a junction I turned down a side turning, went into a shop at the back of a small precinct, and was surprised to find the shopkeeper talking to a customer in Russian. I did not think much about it then, but a few minutes later as I was sitting in front of a snack bar enjoying a glass of freshly squeezed orange juice I looked around and realised. This was Russia! It was all there, the austere blocks of flats, concrete buildings with the aerials on top, and shabby little precincts. You could have picked the whole lot up and dumped it down in the suburbs of Moscow and no one there would have noticed. In general, however, the lady in Be’er Sheva was right, Ashkelon and Ashdod are nice seaside towns, but they are not likely to be in the European package holiday brochures while there is still the occasional rocket attack.

Although I had seen a lot during my visit to Israel, there was still much that I had not seen, especially in the West Bank. It is generally considered inadvisable to go to towns such as Nablus, Jenin, and Hebron, where there is serious poverty and massive refugee camps unless you are accompanied by someone who knows the ropes and has local contacts. I only saw a little bit of the separation wall, in Bethlehem, and afterwards I felt that I could have been more adventurous while I had the Green Peace car.

Israel is a country of enormous contrasts. It is impossible not to be impressed by the rate of development in terms of building and infrastructure, at a level far beyond the imagination of the British government, and many people must be working very hard to make it happen.

At the same time, the country is on a semi-war footing, with a huge military presence and in some areas machine guns are a common sight. The political and religious differences inside and outside the borders are immense, with, as far as I could see, no resolution in sight.

Chile & Argentina 2012

Chile and Argentina 2012

For years I had wanted to go to South America, but was deterred by the supposed danger in travelling around independently as I do. Several countries, including Colombia, Paraguay and Brazil are still a bit dicey, but in recent times the situation has improved and a number of countries are now considered to be reasonably safe. Peru is quite attractive, but half the people I know have been there on guided tours, so I looked for somewhere less popular

After some research on the internet I discovered that it was possible to hire in car in Santiago, Chile and drive over the highest part of the Andes to Mendoza in Argentina, which seemed quite a sensible thing to do. Chile is generally safe, and despite comparatively recent history Argentina was said to be ok for British people as long as discussion about the Falklands is avoided.

On a recent trip to Germany I had picked up a 3-year old edition of Ivanowski’s Guide to Chile, in German, for €2. It is unlikely that many British people have travelled around Chile or anywhere else using an Ivanowski guide, and it was nothing like as good as a Rough Guide or Lonely Planet, but it did have a large road map at the back. Subsequently I lashed out on a new Rough Guide (RG) which provided most of the information for my trip.

To be any good a map of Chile has to be large, because at 2700 miles from north to south it is the longest country in the world, although at its widest point it is only about 150 miles across. To put it in perspective, if you were to cut Chile out of a globe atlas and place the top end on Norway, the bottom would be on Nigeria. The capital, Santiago, is about half way down and is at the same latitude as Johannesburg in South Africa and Perth in Australia. As a consequence of the strange shape of South America the longitude of Santiago is east of that of Boston, although it is only about 70 miles from the Pacific ocean.

Despite its shape, Chile has clear cut natural boundaries, with a vast desert to the north, frozen wastes to the south, the Pacific ocean on the west and the Andes mountains on the east. This makes it impossible to generalise about the weather, but in the Santiago area I expected it to be warm in November.

There are no direct flights from England to Santiago and really it was a choice between going via Madrid, with a short flight and a very long one, or the USA with two fairly long flights. Because of the complications of immigration in the USA I decided on the Spanish route, although I was a bit concerned about the collapsing economy there. The flights were operated by Iberia in conjunction with British Airways and LAN Chile.

In the event everything went quite smoothly, although being crammed into a seat on an A340-600 for 14 hours was no great pleasure, especially as the space and in-flight services were little better than with Ryanair. Owing to a problem which my doctor describes as “common in men of your age” I had an aisle seat at the back near the toilet and had to get up at least 6 times.

Santiago

At Santiago Airport there was an excellent shared minibus system for taking people to their accommodation in the city, and it cost about £7 for 12 miles, although the traffic jams in the city centre were dreadful, practically the worst I have seen anywhere. By the time I got to my hotel I been travelling for about 30 hours.

On the way through the city we used the main thoroughfare, which has the name Avenida Libertador Bernado O’Higgins. Mr O’Higgins, who was presumably of Irish extraction, figures very prominently in Chilean history as the liberator of the country in the 18th century. Many British names crop up in a similar way, examples being Walker, MacIver, Mackenna, and Cox. (Click on picture to enlarge). Av O’Higgins is very long and parts of it were lined with shabby buildings exactly as I expected South America to be. Some of the buildings had big pictures of girls all over them. It was not clear what they were but I think they might be art galleries of some sort and I resolved to go back and have a proper look at the area before leaving Chile.

presumably of Irish extraction, figures very prominently in Chilean history as the liberator of the country in the 18th century. Many British names crop up in a similar way, examples being Walker, MacIver, Mackenna, and Cox. (Click on picture to enlarge). Av O’Higgins is very long and parts of it were lined with shabby buildings exactly as I expected South America to be. Some of the buildings had big pictures of girls all over them. It was not clear what they were but I think they might be art galleries of some sort and I resolved to go back and have a proper look at the area before leaving Chile.

As usual I had booked a cheap hotel on the internet and the room was very small but clean and the people were nice. After getting sorted and resting for an hour or so I walked to Plaza des Armes, a small park which is the centre of life in the city. The hotel was in Providencia, a reasonably smart neighbourhood, and I felt quite comfortable about walking through the streets with my  backpack. On the way I called in at the car rental office, as there had been some last minute problems with the documentation for taking the car to Argentina. Over the previous few weeks I had had considerable email correspondence with a chap named Raphael, and it seemed strange to be meeting him face to face, but he said everything was ok.

backpack. On the way I called in at the car rental office, as there had been some last minute problems with the documentation for taking the car to Argentina. Over the previous few weeks I had had considerable email correspondence with a chap named Raphael, and it seemed strange to be meeting him face to face, but he said everything was ok.

The next morning I collected the car, a Nissen March (known in many countries as the Micra), and was pleased to find that it was in good condition apart from a few minor scratches. Raphael was out and the car was handed over by a pleasant Brazilian chap who said his English was not very good, and when I asked for directions to Los Andes he said “take Hooter Sink Nortay”. He repeated this several times, and it was like Basil Fawlty trying to make Manuel understand something in English, but the other way round, although this man was rather less aggressive than Basil. “Hooter Sink Nortay” was going round and round in my head, when I suddenly exclaimed “Ah! Route Five North!”. My recent attempts to learn Spanish have actually been a dismal failure but the signs to Ruta 5 Norte were easy to find and I was soon on the way to Los Andes. Once clear of Santiago there was little traffic and the road ran for a long way across an arid desert-like plain with rows of small trees as far as the eye could see. After a while I came to a toll booth, the first of many that I was to encounter in Chile. The road then climbed into the mountains via a tunnel for which another payment was demanded.

Los Andes

Eventually I arrived in Los Andes, a small town, and managed to scrounge a free map from the ‘tourist office’, a cabin at the side of the road. From the internet at home I had obtained a list of four hotels and set off in search of them with the map. The first street I tried to drive down had a man at the end in a yellow jacket taking to someone in a car, and thinking he wanted some money I squeezed past and entered the street. It was very narrow with cars both sides and I had to squiggle about to get through. After about 100 yards it was apparent that the road was blocked by a market. With great embarrassment, touching mirrors on both sides and following shouted instructions from the population of Los Andes, including the man in the yellow jacket, I reversed the unfamiliar car through the obstacle course back to the main road. The man in the yellow jacket required payment for his assistance, and I put the incident down to the SHHMS (Should Have Had More Sense) factor, which rears its ugly head somewhere on every trip.

As in many towns in Chile, the streets of Los Andes are laid out in a grid and most are one-way, which is no problem once you get used to it.

Eventually I found a decent, cheap hotel with a secure car park, which is said to be vital anywhere in South America. There certainly seems to be an obsession with security, with the iron railings and big locked gates that you see in pictures of that part of the world, but whether the crime rate is really so dreadful I don’t know. The locals warn you about walking through the streets with anything of value and the guide books tell you to keep the car doors locked and windows closed when driving around, but on the face of it it didn’t seem to me to be any worse than Portsmouth (England) and nothing like as bad as many cities in the USA.

Over the mountains

The next morning I was woken by a loud siren that I thought might be warning of an earthquake but turned out to be the way of rousing the part-time fire brigade. After breakfast I set off for Argentina, over the Andes, passing the highest mountains in the world outside the Himalayas. The road  rises to an elevation of about 3500m. (11,500ft), much higher than any European pass, via a series of over 20 hairpin bends before entering a toll tunnel which cuts off the top of the original pass. The actual border between Chile and Argentina is marked by a sign inside the tunnel and a short distance after the tunnel there was a kiosk in the middle of the road with a man who shouted something in Spanish and gave me three forms. These were an immigration form for me, a form all in Spanish for the car, and a little piece of blue paper with a stamp on it. He said something about another place in “treize kilometre”, but I didn’t know whether this was 3 km or 13km. It turned out to be the main customs post, at 13km, and this was a real old style frontier checkpoint, with several lines of kiosks inside a building. There were 5 kiosks in each line, some Chilean and some Argentine, and no one spoke English.

rises to an elevation of about 3500m. (11,500ft), much higher than any European pass, via a series of over 20 hairpin bends before entering a toll tunnel which cuts off the top of the original pass. The actual border between Chile and Argentina is marked by a sign inside the tunnel and a short distance after the tunnel there was a kiosk in the middle of the road with a man who shouted something in Spanish and gave me three forms. These were an immigration form for me, a form all in Spanish for the car, and a little piece of blue paper with a stamp on it. He said something about another place in “treize kilometre”, but I didn’t know whether this was 3 km or 13km. It turned out to be the main customs post, at 13km, and this was a real old style frontier checkpoint, with several lines of kiosks inside a building. There were 5 kiosks in each line, some Chilean and some Argentine, and no one spoke English.

When I collected the car the rental people emphasised that it was vitally important to follow the correct procedure in the customs. As the temporary importer of the vehicle into Argentina it was my responsibility to ensure that the correct papers were stamped and I must be with the car on its return to Chile, otherwise I would be liable for duty in excess of its value. If it got smashed up in Argentina I had to come through the frontier with the wreckage on a breakdown truck. They omitted to say what would happen if I got smashed up.

In the customs shed my passport, the wad of papers I had for the car and the ones that I had been given by the man a few miles back were all taken and stamped, stamped, and stamped again. A young chap appeared who spoke a little bit of English and asked me for ” the paper with the blue light”, by which I assumed that he meant the little bit of blue paper, which had fallen down between the seats. This seemed to be the most important of the lot, and by the time I finally escaped it was completely covered with stamps.

A few miles further on I was stopped yet again by a man standing in the middle of the road who took the little piece of blue paper, folded it, and put it in a slot in the top of a box. It is impossible to understand the purpose of this arrangement, but I drove away feeling that I might somehow have voted for the next President of Argentina.

Argentina

The mountains on the Chilean side were plain and not very attractive, but on the Argentine side they were altogether more colourful. Although the road on the descent from the pass was comparatively straight the scenery was superb with little traffic. There were several places of interest that I resolved to look at on the way back, and I pushed on to a small town called Uspalatta, where I stopped for a look round. It was immediately obvious that Argentina was less prosperous than Chile, the place having a general run down appearance with many tatty old cars driving about. Only the few main streets were tarmacked, the rest being compacted soil.

road on the descent from the pass was comparatively straight the scenery was superb with little traffic. There were several places of interest that I resolved to look at on the way back, and I pushed on to a small town called Uspalatta, where I stopped for a look round. It was immediately obvious that Argentina was less prosperous than Chile, the place having a general run down appearance with many tatty old cars driving about. Only the few main streets were tarmacked, the rest being compacted soil.

On to Mendoza, which is the second largest city in Argentina. If you are a wine lover you will definitely have heard of it, but it was unknown to me until I planned this trip. It is quite large, population over 110,000, but I quickly found a reasonable hotel within walking distance of the centre, booked for two nights and went to explore.

Mendoza is a totally planned city, after being completely destroyed by an earthquake in 1861. It was rebuilt with wide tree-lined streets, but those I walked through into town were quite shabby with a lot of closed business premises. The pavements were in very poor condition, with large holes and open drainage channels everywhere, and you have to keep an eye on the ground at every step you take. The streets appear to be designed to cope with vast quantities of water, and I can only assume that when it rains it must do so in a big way.

tree-lined streets, but those I walked through into town were quite shabby with a lot of closed business premises. The pavements were in very poor condition, with large holes and open drainage channels everywhere, and you have to keep an eye on the ground at every step you take. The streets appear to be designed to cope with vast quantities of water, and I can only assume that when it rains it must do so in a big way.

The centre is smarter, with shopping streets based around a beautiful large park with four smaller parks nearby, and in contrast to the suburbs there was plenty going on. The main streets were very European in character, with lots of old French and Italian cars, plus a few British ones from the 1960s through to the 80s. Mr.O’Higgins was apparently also in  action here, his name having been given to a park. Like Santiago, Mendoza has a good road system, but again, without local knowledge you can easily get into a mess, as I did when drove down to a big modern shopping mall in the evening.