Florida 2018

CLICK ON PICTURES TO ENLARGE

It was only 15 months since my last visit to the USA, but nine years since I was in southern Florida, that trip having been written up at length elsewhere on this site. It was also my first opportunity to experience a transatlantic flight with a low-cost airline (Norwegian) in a Boeing 787 Dreamliner, from Gatwick to Fort Lauderdale. American immigration procedures seem to change all the time, with some parts of the process now automated, but it appeared to have more stages than before and took just as long.

It was only 15 months since my last visit to the USA, but nine years since I was in southern Florida, that trip having been written up at length elsewhere on this site. It was also my first opportunity to experience a transatlantic flight with a low-cost airline (Norwegian) in a Boeing 787 Dreamliner, from Gatwick to Fort Lauderdale. American immigration procedures seem to change all the time, with some parts of the process now automated, but it appeared to have more stages than before and took just as long.

At the Alamo car rental depot I was sent through to the garage to choose “any car from the medium lot”, which consisted of a row of about 12 cars of various makes and colours. For Florida you need a white car, because however good the air-conditioning is, a darker colour will be unbearably hot inside after it has been parked for some time in the sun. There were only two white cars, and the end I chose a Hyundai Elantra, which is what I had actually asked for.

medium lot”, which consisted of a row of about 12 cars of various makes and colours. For Florida you need a white car, because however good the air-conditioning is, a darker colour will be unbearably hot inside after it has been parked for some time in the sun. There were only two white cars, and the end I chose a Hyundai Elantra, which is what I had actually asked for.

Getting from the airport to accommodation at night in a strange car after a long flight is probably the most hazardous part of the whole trip, but I managed to reach the rock-bottom Motel 6 Dania Beach without incident, in time for a full night’s sleep.

I had originally planned to take this holiday in November, but had to postpone it until March for various reasons. When I rebooked the accommodation I realised that prices were much higher and availability more limited, as early March is the peak season for Florida, and coincides with the students’ Spring Break. Fort Lauderdale was the traditional home for the Spring Break before they moved to Daytona, but it seems to have regained its popularity to some extent.

Florida weather is not totally predictable in March, and when I went out the next morning it was about 55⁰F, which is cooler than I would have liked, although characteristically it warmed up quite quickly into the lower 70s.

In bygone days I always went out for a full American breakfast consisting of a stack of pancakes and syrup together with eggs, bacon, other fried items, and possibly fruit all on the same plate. Sadly my insides will not stand this every morning nowadays, but I did indulge on the first day at Joe’s Café, a popular eating place at Harbordale, about 2 miles away.

In peak season it is difficult and extremely expensive (several dollars an hour) to park in many of the beach areas of southern Florida, and it occurred to me some time before I went that a folding bicycle that I could take in the car would be useful. I had recently seen one in a boot sale in England for £25, and something like that would be perfect. The place to find one would be one of my old haunts, the vast Fort Lauderdale Swap Shop a few miles away on the western side of the town, so that is where I made for after breakfast. The Swap Shop is a huge indoor and outdoor market and boot sale, which turns into a 14-screen drive-in movie theatre in the evening.

The whole establishment belongs to Mr.P.Henn who is a car enthusiast and collects cars mainly with a top speed of about 200mph. He has a museum at the site, and the collection has grown from about 12 on my previous visit to around 30 now.

There were a number of bicycles on offer, but no proper compact folding ones, and I think this is because cycling in America is mainly for people who are too young to drive a car or the lycra brigade, who ride around with the same expression of grim determination on their faces that Americans put into all their leisure activities.

On the way back to the motel I called at three bicycle shops, but all they had in folders were new German Dahon ones made in Taiwan, the same as the one I have at home, so I abandoned the idea. I also went into a Walgreen pharmacy (owner of Boots in the UK) for a couple of things, and was amazed at how expensive a lot of things were. The pound has actually gone up against the dollar since my California trip, and I am sure there has been inflation of the dollar prices in recent times.

The route back to Motel 6 took me along Fort Lauderdale Beach and Las Olas Beach, which were absolutely packed with people and no hope of parking.

The evening meal was something of a surprise. Shortly before going to the States I read a novel by a south Florida author and professor named James W. Hall, involving the creation of a new species of fish called red tilapia, which would be worth a fortune. I had never heard of tilapia, and thought it existed only in the realms of fiction until I looked at the menu in the International House of Pancakes and saw a meal called Tilapia Florentine with baked tilapia as the main ingredient. There are in fact many species of tilapia, though possibly not red ones, and certain aspects of tilapia farming and consumption are controversial. Anyway, it was delicious and there have been no after effects at the time of writing.

No Parking in Little Moscow

The plan now was to spend the next day looking at the east coast beaches down to North Miami, and then drive across to Naples on the west coast in the afternoon In the morning I started out early, but not as early as I thought, because I discovered that the clock had changed by one hour in the night. Motel 6 is actually on route A1A which runs close to the coast right down to Miami via Hollywood, Hallendale and North Miami Beach, this Hollywood being a very far cry from its namesake in California. The whole area is a heavily built-up coastal strip with limited and very expensive parking. I was hoping to get breakfast in a place called Sunny Isles where I spent some time in the late 1980s, and where there are several strip malls (precincts of small shops with time-limited parking). On one these I found a bakery/café with a very pleasant waitress who had worked for a while in London, and after chatting her up a bit she offered to let me leave the car on their private car park for a couple of hours while I went on the beach.

Between the road and the beach are three identical 45-storey skyscraper ‘condo’ blocks and three smaller ones, comprising the Trump International Beach Resort, all built in the last 10 years. At least a third of them are occupied by Russians and the area, including Hollywood, is known as Little Moscow. When I first went there 30 years ago a lot of the residents were elderly German-speaking Jews and, during the holiday season, French Canadian ‘snowbirds’, but most of the holiday accommodation has now gone and the Russians have taken over in a big way.

It was not perfect beach weather, slightly cool and with a strong swell, but ideal for walking down to the wooden fishing pier. In both directions there were enormous buildings as far the eye could see, with a few of the original shabby 2-storey motel blocks tucked in between. Sadly the art deco reception buildings facing the road have long since disappeared. I walked back along the road to the café for another apple pocket (turnover) and coffee before driving along to Hollywood. With some reluctance I put the car in a multi-storey car park at 4 dollars an hour and went through to

the beach. Hollywood has a classical American ‘boardwalk’ (actually tarmacked) on the beach lined with palm trees, a hive of activity, with walkers, skateboarders, cyclists and pedal-powered contraptions carrying up to four people. At the side was also an ingenious continuous wave on which people were practising surfing. This is where the bicycle that I didn’t have would have been perfect. Hollywood seemed to have been spared large-scale development, and most of the single storey motels that I remembered from 30 years ago were still there, albeit somewhat smarter.

Moving on West

Time to drive on to Naples, over 100 miles away on the west coast, via the Interstate I-75 toll road. The toll was $1.50, laughable by European standards, and with the light traffic it took well under two hours to reach the Spinnaker Inn motel. As flat as a pancake and mostly dead straight, the highway runs right through the Everglades. More about that later. The Spinnaker Inn is a traditional motel, where you can park in front of your room, which I like, although the British Foreign Office travel advice is to avoid such places because they are easily accessible to strangers. There were two or three restaurants adjacent to the site.

After surviving the night without getting mugged or shot I drove into central Naples which is a stylish upmarket area with mostly free parking. Presumably this Naples is a one-time descendant of the one in Italy where you would probably be far more likely to get mugged or shot. The open restaurants were very expensive so I went back to the main road and found Another Broken Egg Café for breakfast. As I was a new customer I got two items free!

After surviving the night without getting mugged or shot I drove into central Naples which is a stylish upmarket area with mostly free parking. Presumably this Naples is a one-time descendant of the one in Italy where you would probably be far more likely to get mugged or shot. The open restaurants were very expensive so I went back to the main road and found Another Broken Egg Café for breakfast. As I was a new customer I got two items free!

On to the beach via the vast smart residential area that stretches for miles along the coast. No problem in finding free parking near the wooden fishing pier, which was barred off half way along due to damage from the recent hurricane Irma. Some of the big houses with enormous gardens set back from the beach were also being repaired. After a long walk on the wide sandy beach I went through to Old Naples for a coffee in the Bad Ass Café, the clientele of which did not seem at all appropriate for the name and more like the sort of people you would expect to find in the adjacent smart shops.

Naples to Venice and beyond

Next stop was Fort Myers Beach via Bonita beach. Development has been rife here, with limited beach access and expensive parking in places where it used to be free. As I walked along the beach I came across a bench facing the sea with a big sign stating Courtesy of THE FORT MYERS BEACH DIRECTOR OF SUNSETS Harry N Gottleib, over a picture of a gorgeous sunset. Back in the car it took an hour to drive the three miles to the centre of Fort Myers Beach due to the whole place being taken over by Spring Break students wandering all over the road.

Next stop was Fort Myers Beach via Bonita beach. Development has been rife here, with limited beach access and expensive parking in places where it used to be free. As I walked along the beach I came across a bench facing the sea with a big sign stating Courtesy of THE FORT MYERS BEACH DIRECTOR OF SUNSETS Harry N Gottleib, over a picture of a gorgeous sunset. Back in the car it took an hour to drive the three miles to the centre of Fort Myers Beach due to the whole place being taken over by Spring Break students wandering all over the road.

Probably the most famous thing about Fort Myers is that it was the winter home of Thomas Edison, Henry Ford and Harvey Firestone, among other wealthy northern industrialists. My route took me along the tree-lined MacGregor Boulevard past their homes and the Edison Museum, which I visited years ago. It was slow going all the way to the Tropical Palm Motel, which was considerably less exotic than it sounded.

In the motel I picked up a leaflet about Rick Treworgy’s Muscle Car City, which was on the main road at Punta Gorda, about 20 miles north, and resolved to visit it in the morning. When I got there the sign was in place in front of a large concrete building which was in the process of being

gutted for conversion to another use. I assumed that the museum had finished, and was annoyed to discover later that it had moved to another site about a mile away. A slight consolation was the discovery of a marvellous place called Destination Powersports with a range of fantastic recreational vehicles, the likes of some of which I had never seen before. Called UTVs, which apparently means Utility Task Vehicle, they have a skeletal frame, massive ribbed tyres and a high ground clearance.

From Punta Gorda I cut across to the weird town of Rotunda, a large “deed restricted” retirement community, consisting of bungalows built within a circle of narrow waterways, divided into eight segments, one of which has been left to nature. The circle is about 5 miles in diameter, and most of the shops and services are situated outside it to the north. The whole place was very quiet, almost like a ghost town, and maybe the residents were in the doctors’ surgeries or playing on some of the five golf courses.

From Rotonda I went to somewhere I had never been before, namely Placida, a tiny fishing village on the edge of the Gulf of Mexico. As the name suggests, it was an absolute haven of tranquility on the edge of the ocean, even quieter than Rotonda.

Next stop was Caspersen Beach, a relatively undeveloped place with plenty of free parking in a wooded area within a short distance of the shore just south of Venice fishing pier. Close to the pier is a park with a lake which according to the notices is home to alligators, although I didn’t see any. Certainly not the sort of thing you find in Bognor Regis.

Venice is another smart town, with an Esplanade, fairly similar in character to Naples. After a stretch on US41 again I turned off to Siesta Key and Siesta Village, pleasant not too over-developed places with good

beach access. A group of people on Siesta Key beach turned out to be a yoga class that was apparently open to anyone, although I did not take part. On to Sarasota, another city with a European-style main street, and across a long causeway to St Armands Circle and Lido Key. St.Armands Circle is a large roundabout with a little park in the centre and up-market shops and restaurants around the outside. From here you can walk to Lido Key Beach where there is plenty of free parking.

For 15 miles from St. Armonds Circle to Bradenton Beach the road runs along Gulf of Mexico Drive, a narrow strip of land between the Gulf and Sarasota Bay with spectacular views on both sides in places. Leaving the beach behind I drove on through Bradenton to my night’s stop at the Day’s Inn.

St Petersburg

The plan from here was to drive up to St.Petersburg via the Sunshine Skyway, an 11-mile long causeway with a 4-mile long bridge in the middle of it. It rises to a height of 430 feet and provides superb views across Tampa Bay. The toll for crossing this engineering masterpiece is a mere $1.50. Two long fishing piers beneath it are the remains of a previous bridge that collapsed after being hit by a ship in 1980, resulting in the deaths of a large number of people.

The first target in St.Petersburg was the Tampa Bay Automobile Museum, of which I had been aware for some time, but had imagined that it would not be particularly interesting. In fact, it was really excellent, with a lot of quite rare and technically unusual cars, mainly of European origin. It is always amazing that in America there are European cars that would be hard to find or may not even exist closer to home.

The first target in St.Petersburg was the Tampa Bay Automobile Museum, of which I had been aware for some time, but had imagined that it would not be particularly interesting. In fact, it was really excellent, with a lot of quite rare and technically unusual cars, mainly of European origin. It is always amazing that in America there are European cars that would be hard to find or may not even exist closer to home.

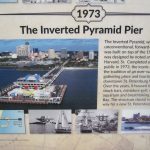

One of the top attractions in St.Petersberg for many years has been its pier, which extends from the centre of the city into Tampa Bay, and has been famous for the building at the far end, in the form of an inverted pyramid. I followed the signs from the freeway to ‘The Pier’, but was very puzzled when I got to the place where I remembered it to be, because the road was closed with barriers, and there was no sign of the unique and iconic building. At first I thought I must be in the wrong place, but eventually realised that the building had indeed gone, this being confirmed by signs showing pictures of the old one and artist’s  impressions of the new one that was being built. It seems that they just got bored with the inverted pyramid and decided to replace it with a new building of entirely different construction. It is impossible to imagine that happening in Europe, but Americans are much more ready to accept change than people this side of the Atlantic.

impressions of the new one that was being built. It seems that they just got bored with the inverted pyramid and decided to replace it with a new building of entirely different construction. It is impossible to imagine that happening in Europe, but Americans are much more ready to accept change than people this side of the Atlantic.

Anyway, somebody gave me his 3-hour parking ticket that still had 2 hours left on it, so I went for a look around the centre of the city, with its tidy streets lined with palm trees and generally upmarket atmosphere. It was then time to go back to the Days Inn Bradenton and spend the evening shopping.

Shopping blues

Not far away was the De Soto Square Mall, which was an example of the parlous state of the American retail scene, and perhaps a warning of the way we are heading in Britain. The shopping malls usually consist of two or more ‘anchors’, big stores such as Sears, Macy’s, Bloomingdales, etc, connected by covered arcades of smaller shops and a food hall. In this case the anchors were Sears and J.C.Penny, which were not exactly booming, and at least half of the other businesses were closed. In the food hall only two places out of about six were trading, and it was altogether a very sorry scene. Efforts are being made to revive it by bringing in entertainment centres and other attractions, but its future obviously very much hangs in the balance. The situation has been described as a ‘retail apocalypse’ which will result in a high proportion of American shopping malls closing in the next few years.

Back to Naples

The next morning I set off to retrace my steps back to the Spinnaker Inn in Naples, but calling at a couple of places on the way, namely Ideal Classic Cars, a museum in Venice, and Fisherman’s Village, a quaint but touristy shopping and entertainment centre on the bank of the Peace River in Punta Gorda.

The museum was really a classic car sales business, but had some interesting, mainly American vehicles on show. Entry was free by registering as a supporter, presumably as they hope to see you as a customer one day. Unlikely in my case.

Fisherman’s Village was very busy, and I had to walk some distance from the car, something Americans do not usually do. It consists of shops and restaurants in a large covered arcade between old wooden buildings. There are actually moorings for fishing boats and a walkway alongside the harbour with pelicans and other marine life around.

Naples is famed for its sunsets, and as it was a particularly fine, clear, evening I made straight for the beach to see it. Harry N.Gottlieb, the Fort Myers Director of Sunsets, does not have a monopoly, and I think the Naples ones are more famous. If it looks like being a good one a large number of people turn out to watch, including the residents of retirement homes on the beach. When I got through to the beach there were already a lot of people there, many sitting on chairs that they brought with them. I have seen Naples sunsets before and clouds often appear on the horizon at the last minute but this one really was exceptional with a clear sky right through to the end. When the sun finally disappeared the spectators clapped, a very American thing to do (they clap when planes touch down safely).

Naples is famed for its sunsets, and as it was a particularly fine, clear, evening I made straight for the beach to see it. Harry N.Gottlieb, the Fort Myers Director of Sunsets, does not have a monopoly, and I think the Naples ones are more famous. If it looks like being a good one a large number of people turn out to watch, including the residents of retirement homes on the beach. When I got through to the beach there were already a lot of people there, many sitting on chairs that they brought with them. I have seen Naples sunsets before and clouds often appear on the horizon at the last minute but this one really was exceptional with a clear sky right through to the end. When the sun finally disappeared the spectators clapped, a very American thing to do (they clap when planes touch down safely).

The next morning, before setting off for Miami I decided to have a look at the beach, but found that it was impossible to park anywhere near. There were many people and families dressed in green outfits flocking to the city centre, and I realised that it was March 15th, St.Patrick’s Day. I have encountered this before in the USA, and it is astonishing that are there so many people who claim to be of Irish descent. The streets around the city centre were all closed to cars with barriers, so I pushed on out of town on US41 towards Miami.

The Everglades

After a few miles I turned off right to Marco Island, which was new territory to me. It is a true island, joined to the mainland by two road bridges, and is mainly residential with limited access to beaches unless you are staying in beach front property. All quite upmarket and undoubtedly expensive.

Returning to US41, within a few miles the road enters the Everglades (though not the National Park) and comes to the turn-off south to Everglades City. I stopped here for a snack at Subway, and while I was in the car park I heard 50 Harley Davidsons approaching at full bore. In fact, there were no Harleys, just a very big airboat packed with people on the river behind the restaurant. Unfortunately I did not have my camera. These machines are considered to be environmentally unfriendly (even more so than Harleys) and are not liked by a lot of people. They are, however, an easy way of getting right into the Everglades and tours are available in various places all the way to Miami, often operated by members of the local Indian population.

Highway 29 leads south from here to Everglades City, which I had not visited for many years, but it was just as I remembered it, with the white City Hall and other buildings spaced out amid palm trees, presenting a very serene image. A few months ago it had been anything but serene, as it was right in the path of hurricane Irma and suffered a considerable amount of damage and floods.

Continuing on the road from Everglades City brought me to Chokoloskee Island via a bridge and causeway. This place is a bit of a shanty town, best known for the Smallwood Store, a wonderful general store dating from 1906 and preserved with all its contents as a museum including a life size figure of Ted Smallwood, its founder, relaxing in a chair.

Retracing my steps back to the junction with US41 (no alternative), I turned right for about 17 miles to Monroe Station, and then turned off again on to the unpaved Loop Road which goes south for several miles deep into the Everglades before turning east and eventually joining up again with US41. It is generally against the rules to take a rental car on unpaved roads but as the Loop Road has a number and is a recognised tourist route I think it is an exception. The surface could best be described as fine white shale, which billows up into a cloud of dust behind every vehicle that passes under dry conditions, but the traffic density is usually quite low so it is not too much of a problem. The large potholes that existed when I first drove it 30 years ago have now mostly disappeared.

The trees and vegetation extend right up to the edge of the road, but periodically there are clearings where the true nature of the Everglades can be seen close up. Essentially it is partially-flooded grassland which supports a unique range of flora and fauna much of which is not immediately apparent. It is quite flat, and while there are trees in abundance, mostly they do not grow very high, so it easy to drive through it and see it as just another forest. The water on which it depends is actually a slow-moving river 60 miles wide and 100 miles long, stretching from just below Orlando to where it enters the sea at Florida Bay.

It is an area of immense ecological importance, and despite its National Park status it is constantly under threat from surrounding human activity. To the average tourist it does not have the same stunning impact as, for example, Niagara Falls or the Grand Canyon, but it is no less important in the world of nature.

The human inhabitants of the Everglades are mainly native Americans in the form of Seminole and Miccosukee Indians whose forebears were driven south as the white settlers advanced from the north. In addition some war veterans and other people who wish to live away from the mainstream have property tucked away among the trees and swamps. It is considered very inadvisable to approach such premises. Back on the main road to the east I passed the Miccosukee Indian Village which is a major tourist attraction, but was too late to go in.

On the way back to the airport the next day I was planning to have a look at the fantastic art deco area of South Miami Beach which I had not seen for many years, but the hotels in any part of Miami are wildly expensive, and I decided to stay in Homestead, a rather ordinary town a few miles away. Homestead is in fact not rather ordinary, but very ordinary, its only saving grace

being a short stretch of main street with antique shops and cafés

Art Deco Saved

Parking in central Miami on a Sunday in peak season seemed to be from $20, so I went straight through to South Miami and quickly found Collins Avenue and Ocean Drive, the heart of the art deco district. When I first went there in the 1980s the movement to save these wonderful buildings from demolition was only just getting under way, and many were in a bad state. It was considered dangerous to walk off the main thoroughfares at night, or even during the day in some places. The restoration of the buildings combined with general smartening up and better street lighting has transformed the whole place. The area is thriving, with traffic on Ocean Drive proceeding at a snail’s pace, which suited me, as it afforded a better opportunity study the stunning architecture. Unfortunately my camera battery packed up and I am never very successful at getting pictures with my mobile phone.

It is also astonishing how the art deco buildings continue as you drive northwards on A1A, the coast road. Years ago I knew this stretch of road quite well, and the buildings must have been there all the time, but were so shabby that they were not really noticeable. Presumably heightened interest and increasing values have been a driving force for their renovation.

As mentioned earlier, this trip would have been better had it not been at the height of the tourist season, but at least the weather was perfect for walking about, mild with, unusually, no rain.

Albania, Macedonia, Greece 2017

CLICK ON PICTURES TO ENLARGE

Albania, Macedonia, Greece 2017

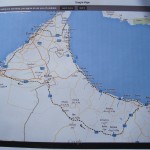

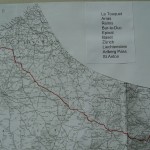

This would be my second visit to Albania, the first having been eight years earlier, when I went to the north of the country for a few days. An account of that trip can be found elsewhere on this site, and ideally should be read before reading this one. The plan now was to fly to Tirana, hire a car and drive to Thessaloniki in Greece via southern Macedonia, then across northern Greece to the Adriatic and up the west coast of Albania back to Tirana, basically a circular tour.

This would be my second visit to Albania, the first having been eight years earlier, when I went to the north of the country for a few days. An account of that trip can be found elsewhere on this site, and ideally should be read before reading this one. The plan now was to fly to Tirana, hire a car and drive to Thessaloniki in Greece via southern Macedonia, then across northern Greece to the Adriatic and up the west coast of Albania back to Tirana, basically a circular tour.

The only flights to Albania were, as before, by BA from Gatwick, but as I stood in the queue for the plane I realized that the make up of the passengers was quite different. Instead of being predominantly male there were now a fair number of women and children. On arrival in Tirana there was still the mystery over the division into ALBANIAN CITIZENS and OTHER NATIONALITIES, most of the latter not being British, so what were they?

Because of the late evening arrival I had booked a room at the Jurgen Hotel directly opposite to the terminal, thereby avoiding the taxi touts. This was a smart hotel for £35, although I had to go to the Best Western next door for a meal. Breakfast at the Jurgen was slightly odd, consisting among other things of scrambled egg and prunes, but it was quite adequate.

Several of the well-known rental car companies operate in Albania, but at the planning stage I had to dig deeply to find one that would enable me to take the car into Macedonia and Greece. Bearing in mind that Albania used to be regarded as second only to India for bad driving one would have thought that most firms would have been pleased for someone to take the car out of the country, but the only one that provided that facility was Sixt, who had a desk at the airport.

The man from Sixt turned up at the desk more or less at on time and took me to their depot round the corner, where I was introduced to my Hyundai Accent Diesel. Considering that it was Albania there was remarkably little body damage to note down, and I was soon on the way to Tirana.

Within a short time I noticed two differences from my trip eight years earlier, namely that the traffic was much calmer and that there was far less rubbish around everywhere. It seemed that there were now properly organized refuse collections, with bins at the roadside in many places. The predominance of old Mercedes cars was less striking, with more people driving typical modern small cars as elsewhere in Europe.

My route took me right through the middle of Tirana, past Mr.Hoxha’s famous pyramid, which contrary to my expectation did not appear to have been renovated and was in much the same dilapidated condition as when I last saw it. My initial target was a town called Elbasan some distance the other side of Tirana, and I was struggling fairly successfully through the awful city centre traffic until I came to a massive roadworks with no direction signs of any sort. With the help of the map in my tablet I eventually got on the road to Elbasan after driving through barriers on a stretch of closed road which was a building site, and it was very slow going for about 30 miles with endless roadworks and diversions. This area has typical Albanian semi-urban landscape, with an inexplicably large number of filling stations and part-finished buildings.

expectation did not appear to have been renovated and was in much the same dilapidated condition as when I last saw it. My initial target was a town called Elbasan some distance the other side of Tirana, and I was struggling fairly successfully through the awful city centre traffic until I came to a massive roadworks with no direction signs of any sort. With the help of the map in my tablet I eventually got on the road to Elbasan after driving through barriers on a stretch of closed road which was a building site, and it was very slow going for about 30 miles with endless roadworks and diversions. This area has typical Albanian semi-urban landscape, with an inexplicably large number of filling stations and part-finished buildings.

Macedonia

The 40 miles from Elbasan to the Macedonian border was much more pleasant driving with less traffic and good scenery. I had no idea what to expect at the border, but was pleased to find only very few vehicles going my way. The people at Sixt told me that I must buy a car insurance green card for Macedonia and Greece from a kiosk at the customs post, and that proved to be extremely easy for a fee of 40 euros. Neither Albania nor Macedonia use the euro but they seem to expect foreigners to do so. My passport and the car papers were checked at the customs on both sides of the border, with a few questions on the Albanian side, but I was through quite quickly.

Such was my poor planning for this trip that it was not until I was in the country that I discovered that the Macedonian language uses the Cyrillic character set, like Russia and Bulgaria. The language is closely related to Bulgarian and entirely different from Albanian and Greek, the other two countries on my itinerary. The Cyrillic languages are actually quite easy to cope with if you do a bit of brushing up in advance (which I hadn’t this time), whereas Albanian is impossible and Greek, well, it’s all Greek to me.

There are complications concerning the name of the country, because the Republic of Macedonia, as it calls itself, covers about one third of the geographical region known as Macedonia which extends into neighboring countries including a large part of northern Greece. As a result the Republic of Macedonia is known by the UN, EU, and NATO as FYROM (Former Yugoslavian Republic Of Macedonia), and that name appears on some road signs.

From the border the road follows round the shore of Lake Ohrid, passing through a small town called Struga, with its pleasant lakeside promenade. The next town, Ohrid, was described in my guide book as a jewel in the crown of Macedonia and had a spa-like atmosphere in its lakefront region.

My night stop was to be in Bitola, the second city of Macedonia (the capital is Skopje), about 40 miles from Ohrid. By now I had the impression that the pace of life in Macedonia was considerably slower than in Albania, with an economy based more upon agriculture. Once clear of Ohrid I seemed to be making good progress on a smooth road through heavily wooded countryside, until encountering a diversion where the road in the direction I was going was being rebuilt. As well as slowing me down this took me back in time to something I had not seen since Belgium in the 1960s, namely the type of road surface called pavé, small rough stone blocks which would set the car vibrating from end to end and shake the fillings out of your teeth. This went on for several miles in the form of a narrow hilly lane with one-way traffic through a forest before rejoining the original route.

Perhaps the best description of Bitola is simply ‘old-fashioned’. It is a very old city, dating from about 4BC and has a chequered history but most of the buildings today are from the Ottoman era or later. At one time it was known as the ‘City of Consuls’ because many countries, including Britain, had consulates there, but it now seems to be of less political significance.

The Hotel Bastion lived up to its name, being a substantial three-storey detached building with one rather serious man in charge and apparently no other guests apart from myself. He said they sometimes had English guests in the summer, although I would imagine that they

were few and far between. The hotel did not do food, and the man recommended a restaurant in the main street which was only about 100 yards away. I had no Macedonian currency, but fortunately the restaurant took Euros. Looking round the town afterwards I got the impression that it was not one of the most prosperous places in Europe. At breakfast time I wandered back to the main street which was still largely asleep and eventually found a hotel that served non-residents.

Into Greece

The drive to the border crossing into Greece was quick and easy, again with just a few vehicles in front at the customs posts and brief document checks. At Niki, shortly after the frontier post the road turned into a superb newly-built motorway for about 12 miles, with not another vehicle going in my direction and few the other way. If more British people could see their money being spent in this way by the visionaries and dreamers of the EU they would have no reservations about our decision to leave. It will be very many years before there is sufficient traffic travelling from Greece through Macedonia and beyond to justify this expense, especially considering the economic state of Greece.

On the map the main road to Thessaloniki from near Florina via Edessa and Giannitsa looks interesting, with potential for good scenery, but in the event it was a disappointing drive. As mentioned above, the Greeks refer to this area as Macedonia (or Makedonia) and many place names are given in Cyrillic and Greek characters but not Latin (English) ones. On the approach to Giannitsa I saw the first signs of the Greek economic disaster. For some distance there were factories either closed or showing little sign of activity, with just a few cars outside and maybe one truck.

Thessaloniki

Approaching Thessaloniki, Greece’s second largest city it was the same story. My hotel, the Rotunda, was near the centre, facing the main railway terminus and at the start of a massive construction project to build a metro. After checking in I walked around the streets behind the hotel and the consequences of the recession were all too clear, with boarded up shops and dilapidated empty buildings. Just to bring home the misery I was chased by an angry dog and bitten in the back of the leg. Fortunately my jeans prevented any serious injury.

To see the sights of Thessaloniki I had only the next morning, so I left the car in a very expensive city centre car park and went on foot from there. A young man involved with the car park spoke exceptionally good English and when I complimented him he said he had lived in Uxbridge for some

time as a student at Brunel University. Brunel is a technical university and it seemed odd that he chose to return to the poor employment prospects in Thessaloniki unless, of course, he was the car park operator, in which case he was probably making more money than he could make as an engineer anywhere. Following his advice I quickly found the old town area with its ruins, which just went on and on as I climbed up the hill towards the back of the city.

The route took me up a long fairly steep path alongside the ancient walls, and I had another encounter with an angry dog whose owner apparently lived in a sort of hole in the wall. He made no attempt to control the dog as it ran round me growling and snarling. If the intention was to deter strangers from going close to his property it was successful, and I sought a different way back. I did not manage to get to the top of the hill, but was high enough to see across the whole city to the harbour and sea beyond.

The route took me up a long fairly steep path alongside the ancient walls, and I had another encounter with an angry dog whose owner apparently lived in a sort of hole in the wall. He made no attempt to control the dog as it ran round me growling and snarling. If the intention was to deter strangers from going close to his property it was successful, and I sought a different way back. I did not manage to get to the top of the hill, but was high enough to see across the whole city to the harbour and sea beyond.

Straight down the hill brought me back to the ferry terminal and smart promenade which is bisected by a beautiful paved square with classical buildings. At the far end of the promenade is the White Tower, a famous monument and museum which I unfortunately did not have time to visit.

paved square with classical buildings. At the far end of the promenade is the White Tower, a famous monument and museum which I unfortunately did not have time to visit.

Back to the car and on the way to my night stop, a town called Ioannina, about 160 miles south east of Thessaloniki via a motorway passing through beautiful mountainous countryside. The extraordinary thing about this road was the number of tunnels. I lost count en route, but checked on the map afterwards, and there were 38, ranging in length from 50 yards to about 2 miles. It was a toll road with 4 or 5 payment stages along the way, the charges actually being remarkably low, a fraction of those in France.

Ioanninia

Ioanninia is a town of 80,000 inhabitants with a fair amount of industry and an area of historic buildings alongside a large lake. It had the atmosphere of a Swiss lake resort, even down to a Hotel du Lac which was well outside my price range. There were a fair number of hotels, none of which seemed to have any vacancies, rather to my surprise considering that it was a Thursday evening in April. Eventually I found a room in a small old-fashioned hotel more or less fronting on to the lake, and set off for a look round the town, starting with the old part. The first thing I noticed was that all the eating and drinking places were crowded with young people, and later discovered that the town is home to 20,000 students. It gave the impression of being a thriving place, very different from Thessaloniki, with shops open until late in the evening, including many with windows full of expensive watches like those to be found in Interlaken.

Ioanninia is a town of 80,000 inhabitants with a fair amount of industry and an area of historic buildings alongside a large lake. It had the atmosphere of a Swiss lake resort, even down to a Hotel du Lac which was well outside my price range. There were a fair number of hotels, none of which seemed to have any vacancies, rather to my surprise considering that it was a Thursday evening in April. Eventually I found a room in a small old-fashioned hotel more or less fronting on to the lake, and set off for a look round the town, starting with the old part. The first thing I noticed was that all the eating and drinking places were crowded with young people, and later discovered that the town is home to 20,000 students. It gave the impression of being a thriving place, very different from Thessaloniki, with shops open until late in the evening, including many with windows full of expensive watches like those to be found in Interlaken.

Then came the big mistake. As I had eaten well earlier in the day I decided to have just a large ice cream in a restaurant specialising in such things, and before I got back to the hotel I realised that it was lying heavily upon my stomach. That was not to be for too long, because before going to bed it came up in five stages, with two more the following morning. I cannot remember what happened at breakfast time, but I don’t think it was very much. In fact, not much happened with regard to eating for the next three days.

The most direct route from Ioannina to Albania goes north west to Gjirokaster, some distance from the coast, but I wanted to follow the coast road from the border to Saranda, a resort facing the Greek island of Corfu. This meant rejoining the motorway for about 50 miles to the port of

Igoumenitsa and driving up to the border crossing at Konispol from there. The road network on the Greek side in this area is vague to say the least, and signposting almost completely absent. Albania did not seem to exist and the customs post was remotely situated on top of a mountain like something out of a film set. The man on the Albanian side studied my passport for about five minutes while I sat there with the engine running, presumably because he had nothing else to do.

Saranda is a well-developed resort built around a bay, and undoubtedly gets a considerable boost to its tourist trade through day-trippers on the ferry from Corfu. My maps showed a concentration of hotels at the northern end of the coastal strip, and I found a balcony room overlooking the beach in one called the Apollon. It gave the impression of being recently built, and when I asked the young lady in reception how old it was she said it was started in 1999 and finished in 2007. This rate of construction seems to be par for the course in Albania, and judging by the number of part-finished buildings everywhere I think many take much longer than that to complete.

Striking features of the hotel were a large mural in with a circular mosaic several yards in diameter in front of it in the entrance hall. The mural depicted a scene of debauchery and was presumably a copy of an established work of art, and the mosaic reminded me of the black magic circle in Dennis Wheatley’s “The Devil Rides Out”. At least the guests will have somewhere to stand if the Angel of Death turns up on his horse.

Striking features of the hotel were a large mural in with a circular mosaic several yards in diameter in front of it in the entrance hall. The mural depicted a scene of debauchery and was presumably a copy of an established work of art, and the mosaic reminded me of the black magic circle in Dennis Wheatley’s “The Devil Rides Out”. At least the guests will have somewhere to stand if the Angel of Death turns up on his horse.

The general standard of public safety is still lower in Albania than most of western Europe. The outside concrete staircase leading down to the hotel car park had a top step which was twice as high as all the others, and as I walked into town I encountered large unprotected holes in the pavement. For a stretch of about 20 yards there was a sheer drop of 10ft down to some waste land on the side of the pavement away

from the road. At one point a thin concrete ledge stuck out over the pavement at eye level, and wherever you are you have to pay attention to your immediate surroundings. Not ideal for those who walk along staring at their mobile phones.

Apart from this Saranda is a pleasant resort town, with a promenade around the centre of a horseshoe-shaped bay.

Adriatic coast road

The plan for the next day was to drive 77 miles north to Vlora, the next main town on the coast. From the map I was expecting it to be a spectacular drive, and it was, by any standards. For much of the time the road ran close to the shore with endless bends and a zig-zag climb to over 3000ft, leading to a viewpoint. The main road was well-surfaced, but a couple of times I turned on to side roads that appeared to lead to places of interest and as usual in Albania they just turned into rough tracks or fizzled out altogether.

The plan for the next day was to drive 77 miles north to Vlora, the next main town on the coast. From the map I was expecting it to be a spectacular drive, and it was, by any standards. For much of the time the road ran close to the shore with endless bends and a zig-zag climb to over 3000ft, leading to a viewpoint. The main road was well-surfaced, but a couple of times I turned on to side roads that appeared to lead to places of interest and as usual in Albania they just turned into rough tracks or fizzled out altogether.

The traffic was light and on one occasion I came round a bend in a village to a find the roadblocked by a lorry with crane unloading building materials. There was no alternative route, so I and the few vehicles that came up behind me just had to wait about 20 minutes until the job was done.

Vlora

For about 12 miles before Vlora the road ran through a number of attractive little beach resorts with hotels and restaurants before turning into a dual carriageway under construction, leading to the town centre. It was very much a case of work in progress and will undoubtedly be an impressive promenade once it is finished, but it was a mess and impossible to stop and look for a hotel until I reached the end of it. The only hotel that was easily accessible was Hotel Partner, a large modern building in the town centre, so that is where I finished up.

The central area was modern, with many quite impressive buildings, but an incongruous

feature was the number of large diesel generators everywhere. I did not remember seeing any in Saranda, although Albania is notorious for its inadequate power supplies and it seems that the situation had not improved in some areas in the 8 years since my last visit. There was not more mains electricity, just more generators, which are very inefficient and bad for the environment.

Driving in Albania is always full of surprises, and in the course of driving around Vlora I came across a stretch of road about 400 yards long surfaced with a layer of wet tar that had just been applied by a machine that was disappearing into the distance. There were no signs or barriers of any sort, causing chaos for the drivers who suddenly encountered it. Many of the other side roads in

the town were in a bad state, some completely impassable due to obstructions of one sort or another. Vlora is actually on the side of a large bay, with the beach front facing the heavily wooded hills of a nature park on a promentary, and one day, if and when the construction work is finished, it will be an attractive seaside resort.

Vlore to Durrës

During the 75-mile journey from Vlora to the next coastal town, Durrës, the whole character of the surroundings changed. The road was largely dual carriageway situated some distance from the coast, with roughly-surfaced stretches running through run down areas.. The standard of driving deteriorated, with cars swerving all over the road to avoid the pothole as in India, and the scenery became more industrial. Durrës is the seaside town for Tirana, the capital, and it was a return to the concentration of half-finished buildings and filling stations that dominated the start of my journey.

The main road into Durrës was in much the same state as the one into Vlora – just a massive construction site. It was Sunday afternoon and the place was heaving with people, including a couple of wedding parties driving through the town with much horn-blowing and general commotion as is customary in those parts. At the far end of the road I parked and went through to the beach, which was a wide stretch of heavy sand, quite clean but almost deserted.

There were a lot of hotels on the side of the road backing on to the beach but with the roadworks it was hard to get to any of them or park and after trying three or four which were full I decided to go back to the coastal strip at Shkallnur that I had passed on the way in.

After struggling through the narrow back streets of Shkallnur I found a hotel with the strange name of Ylli I Detit and

acquired a room with a balcony overlooking the beach. The hotel did meals but I was still a bit under the weather from the ice cream poisoning and all I could manage was soup. It was time for a long walk on the beach, which like the one in Durrës, was quite pleasant and almost deserted.

When I came down for breakfast in the morning I was somewhat surprised to find that there appeared to be no one else in the building. It was the hotel equivalent of the Marie Celeste – everything in place but just no people. Eventually I found a very young lady in staff uniform who spoke no English whatsoever. It was clear that breakfast was not likely to be forthcoming, so as I had already paid for the room I walked past the unmanned reception and departed.

A short distance along the main road to Durrës was a petrol station with an excellent café, after which I went through into Durrës centre, which was much larger than I expected and unlike a lot of places had properly surfaced streets. Some accounts describe Durrës as a dismal place, but it seemed to me to be bustling with activity, much more than I would have expected for a Monday morning. The afternoon was spent taking the car back (undamaged, amazingly) and dealing with the flight home.

Albania is a conundrum. It is supposed to be a poor country and yet everywhere you go there seems to be a lot of activity, with quite large public projects underway, especially in the cities. There is said to be corruption at high level and a general belief outside the country that there are many people engaged in criminal activity such as people-trafficking and money laundering, but Albanians will tell you that the bad people have left the country and are carrying on their evil deeds elsewhere. This may well be true.

Japan 2015

CLICK ON PICTURES TO ENLARGE

JAPAN 2015

This was to be essentially a holiday combined with a brief visit to a Japanese company with which I have had a business relationship for many years. It would be my second trip to the country, with a similar itinerary to the one I had made eight years previously, travelling around by self-drive hire car. When I originally suggested that idea the advice I was given by people who knew anything about Japan ranged from 'inadvisable' to 'impossible', but in the event it was very successful. Starting from Osaka the route covered about 1000 miles, taking in coastal areas, mountains, beautiful countryside and several major cities. Car museums as well, of course.

Despite my experience, in planning this new 11-day trip I made a major blunder. After booking the flights with Emirates I discovered that it was difficult to make any hotel reservations for the first five days that I was going to be in Japan because the three week days were public holidays. The Monday was Respect for the Elderly Day, which I rather liked, the Wednesday was Equinox Day, and Tuesday was a holiday because the other two were. The Japanese are inveterate travellers, and when they decide to move around they do so in a big way, putting a lot of pressure on accommodation and transport. There were still 8 weeks to go, and with great difficulty I managed to book hotels for the whole route, mainly using Booking.com, but it reduced my flexibility and would create big problems if I lost a day anywhere. Also I had to alter my business visit, and the roads were likely to be even more congested than usual.

Hello, Japan. Dancing chairs and bottled sweat.

About 25 hours after leaving home I went into the station at Kansai Airport to get the Haruka Limited Express train to Shin-Osaka, and was immediately left in no doubt that I was in Japan. The train pulled in exactly on time, and I was just entering the carriage to take my numbered seat when a man stopped me and told me to wait behind a line on the platform. He wheeled a trolley full of cleaning stuff into the carriage, and then something happened straight out of Alice in Wonderland. All the seats, which were in lines of 2 or 3, started spinning round on their bases individually. It was just like some sort of crazy Mad Hatter's dance, and appeared to be part of the cleaning procedure, but was actually a way of turning the seats round to face the direction of travel for the return journey as the train was at the end of the line.

It was too dark to see anything much outside, so I took the opportunity to check my navigation arrangements. Finding the way in Japan can be very difficult and locating specific addresses is a big problem even for the locals because in most places buildings are not numbered in sequence along a road or street, but are identified by three numbers referring to the district, block and the number within the block. This last number may be determined by the order in which the buildings were erected, which is not very obvious to a foreigner. If a street has a name it will almost always only be in Japanese unless it is a major route.

To find a particular building you really have to know exactly where it is on a map, and there is something rather peculiar about the Japanese and maps. The maps you find in leaflets and public places are strangely presented and usually do not have north at the top. If you buy a local map it will be entirely in Japanese. Of course, you can always ask somebody, but almost nobody speaks English, which means that they will go off in search of someone who does. As a point of honour they will not let you go until they are satisfied that they have met your needs, which can take a very long time. Businesses often have outline maps on which they will mark the place you are looking for, but they usually get it wrong. It is no good showing someone an address in English because they won't be able to read it, and if you have the address in Japanese you won't be able to read it!

Rental cars usually come with satnav, but it will be all Japanese apart from the road numbers. This means that you need GPS in a phone or tablet, and there is still a problem, because for some strange reason to do with copyright the usual map providers (Google, Bing, HERE) do not have offline maps of Japan. However, after much research I found a modified version of Bing Maps for my Windows phone, and MapsMe for my Android tablet.

Back to the train, and this was the opportunity to see whether the GPS worked with the maps, because I couldn't do it England. To my great relief the little arrows moved along the maps and showed the position of the train, so that I could judge exactly when it was going to get to Shin-Osaka station, although there were clear indicators in the carriages anyway. I chose Shin-Osaka as my base because I knew the area from my previous visit. It has lots of hotels, was convenient for car rental and not too far from my business associates’ headquarters.

Shin-Osaka might have lots of hotels, but I had only been able to find one with a vacancy for the day of my arrival, and in my estimation it was at least twice the price that it should have been. It was very close to the station in a road alongside the railway lines, and I must admit that I did wonder whether it offered services over and above those required for a normal night’s sleep, but there was nothing untoward in the reviews. The name LiveMax also seemed a bit strange, but in fact it is part of a large Japanese hotel and real estate group, and was perfectly respectable.

In the last thirty hours I had had a succession of airline meals, so I was still a bit hungry, and after checking in I went along the street to get something from a convenience store. On the way I passed several of the refrigerated drinks dispensing machines found everywhere in Japanese towns, and containing among many other things bottles of Pocari Sweat and Calpis energy drinks, always a source of amusement to native English speakers. They taste as bad as their names suggest, although Pocari is not actually bottled sweat, but just intended for sweat replacement.

These are just two examples of the very widespread use of English names for products and businesses, which seems very odd in a country in which so few people speak the language. Most hotels have English names, and the two most popular convenience stores are Lawson and Family Mart. Almost every door for public use in Japan has PUSH and PULL on it, a point that I raised with my business associates in a general discussion until I realized that it was dangerous ground and changed the subject.

Mountains and mad motorcyclists.

The next morning I checked out and went to pick up my car from Times Car Rental, a short walk from the hotel. Shin-Osaka, like most urban areas in Japan, is totally safe but visually unattractive, a consequence of the headlong rush for development in the 1960s and 70s. The main street, if you could call it that, is literally overshadowed by a multi-lane elevated highway running for its entire length (and far beyond), with two high level railway stations.

The staff in the car rental office did not speak much English, but after examining my credit card and International Driving Permit they handed me some forms in English to read and sign where indicated. A man took me outside to introduce me to my silver Mazda Demio (Mazda 2 in England) and then left me to get sorted out. Driving in Japan is on the left hand side of the road, with the steering wheel on the right, as at home, but there was one confusing thing, in that Japanese cars in Japan have the lever for the indicators on the right and one for the windscreen wipers on the left. It took me several days to get used to that, and for a time I kept switching the wipers on when I wanted to turn.

Seventy-two percent of the area of Japan is mountainous, which means that a large proportion of the remaining land is built up, with vast, seemingly endless, conurbations along the coasts. My next overnight stay was to be in a small town called Obama on a relatively undeveloped stretch of coast about 50 miles north of Shin-Osaka. It was the other side of a range of mountains, and there were basically three ways of getting there, one being made up of comparatively minor roads across the mountains, and the other two being expressways (expensive toll motorways) on lower lying land to the east or west of the mountains. These last two were each about 100 miles long, and the more direct route was actually about 90 miles, because it squiggled about so much.

There was an element of risk in the last route, as Japanese mountain roads are subject to closures during periods of bad weather, including heavy rain, of which there had been plenty prior to my visit. On the other hand at holiday time there could be problems on the expressways, as on British motorways, and my inclination was to take the mountain route. The traffic north of Osaka on the Sunday morning was horrific and I spent about two hours going nowhere, mainly because of people queuing to get into shopping malls. However, once I got out of that area the traffic cleared and I made quite good progress.

The road ran mainly between tree-covered hills, with villages and a couple of small towns along the way. For some distance it was close to an expressway on which signs at the intersections warned of queueing traffic, so I think I made the right decision to avoid using the supposed high-speed route. For the last forty miles to Obama there were few other vehicles apart from lunatic motorcyclists flying round the endless hairpin bends with their knees scraping the road. The scenery was not as spectacular as might be expected from the map, because of several tunnels through the highest mountains, including one about a mile long.

Obama festival chaos

At 4.30 I arrived in Obama, to find the streets leading to my hotel closed off by people with batons standing in the road. In Japan there are lots of people with batons controlling the traffic, some obviously police, but others employed by businesses or for special events. Nowadays they have batons with lights in them like the light sabres in Star Wars, but shorter and the lights are red. In the distance I could see people marching in traditional costume and there was obviously a festival of some sort in progress.

Eventually I managed to get to the hotel, which was at the centre of the action, and once sorted I went for a walk around. It seemed that there were several groups marching about, two or three of them with marvelous tall medieval carriages packed with people, pulled by strong men with ropes. The carriages were made of wood, including the wheels, and were draped with elaborately-patterned cloths.

The main street was lined with stalls selling the usual tourist fare and all sorts of unrecognizable items of food, none of which appealed to me. At one end of the street was a large shrine, with a kind of altar in front of it and brightly coloured ropes hanging down with enormous tassles. People would come and bow for a while before shaking the tassles, causing bells to ring, presumably as a form of prayer. After a good and cheap rice meal in a restaurant I walked around the town and through to the promenade which overlooked a bay on the Sea of Japan. Obama was an attractive place and I felt pleased with my choice of night stop.

Breakfast in the hotel the next morning was not available to me because I had not booked it in advance. The streets of the town, with colonnades, were deserted, and the shops mostly closed but I resorted to breakfast in a convenience store before exploring the town a bit more. Eventually I found a fair part of the population in a food and fish market near the harbour, where a vast variety of freshly-caught fish were beautifully displayed on slabs.

Heavenly views, tunnels and eating with the locals

The plan for day was to follow the coast northwards for about 80 miles and then turn inland to a city called Fukui. Soon after leaving Obama I followed

a sign to the Angel Scenic Drive which led me on to a cul-de-sac mountain road to the top of Mount Kusuyagadake, on a peninsular. It lived very well up to its name with superb views across the bay and ocean on both sides. At the top was a massive car park with about three cars in it, although the inevitable group of motorcyclists turned up after a few minutes. A very nice well-travelled couple from Kobe came over and talked to me for a while. They were astonished that I was driving around on my own, because few Japanese people have ever driven in a foreign country and they find it hard to imagine doing it.

By now I was completely used to the ridiculously low speed limits on Japanese roads. For almost the entire distance since I left Shin-Osaka the speed limit had been 40kph (25mph) or 50kph (31mph), even on open country roads. These limits are normally exceeded by a margin of about 50%, i.e. people do 60kph in the 40 limit and 75kph in the 50 limit. Motorcycles go as fast as they can. Police cars are few and far between as are cameras, and little effort is put into enforcement.

The main road wended its way along the coast past tiny fishing ports, from time to time passing through tunnels where the mountains came down to the sea. I counted nine tunnels in about thirty miles to the town of Tsuruga. Continuing to follow the coast line I stopped for a walk in a couple of small places right alongside the ocean and was surprised to find that there was lots of free parking and not many people about. It is always said that you cannot find anywhere to park in Japanese towns and cities, which is not actually true. It is usually easy to find somewhere, but just very expensive, although no more so now than in cities like London, Brighton or Oxford. In some places the main road (Rt.305) was uncomfortably narrow, which might explain the lack of buses, and therefore people.

Eventually I turned inland to Fukui, an industrial city which has a population of 267,000, and managed to find the Route-Inn Court Hotel, in the middle of a big commercial development. For my main meal of the day I went into a nearby restaurant, sat down and waited to be served, without realizing that it used a system that is widespread in the sort of cheap Japanese places that I frequent but had forgotten about. A member of staff came over and indicated that I should follow him into the lobby, where there was a big cabinet with dozens of tiny pictures of meals. Below each picture was a brief description of the meal in Japanese, the price, a button, and a small slot. The procedure is to decide on a meal that does not look too revolting or poisonous, put an appropriate amount of money into a big slot on one side, and press the relevant button. A little ticket then pops out through the small slot for you to give to someone in the restaurant and after a few minutes the meal will be put in front of you. At that point it is no good saying “Oh no, I pressed the wrong button”. You just have to knuckle down and get on with it, chopsticks and all.

Old cars, old houses and scenery

For most people the highlight of a trip to Japan would be a visit to a historical monument or cultural event of some sort.

For me it was the Motorcar Museum of Japan at Komatsu, a name that will be familiar to anyone in the building industry as it is the home of one of the world’s largest construction machinery manufacturers. The museum is an extraordinary place with an extraordinary history.

An extremely imposing European-style red brick building, it was put up by the man who introduced such bricks to Japan during the massive building boom of the 1960s and ‘70s. He had a fleet of lorries that delivered the bricks to sites all over the country, and one of his customers asked him to take some old cars away on the empty lorries after the delivery. He offered this service to other customers, and eventually finished up with 500 cars in a field, leading to the establishment of the museum . In front of the building stand two classic British red telephone boxes and a matching red postbox, with a notice in Japanese that presumably states “Do Not Post Letters in This Box”. Apart from the display of cars there is another rather unusual collection ‘Urinals From Around the World’, twenty seven in total, all in working order and labelled with their country of origin. Even I couldn’t test all of them during my visit.

At mid-day I left the museum with a long cross-country drive in front of me, to the ancient town of Takayama, which is remotely situated in a mountainous area of Central Honshu. From Komatsu it is possible to cover a large part of the journey on expressways, including an eight-mile long tunnel, but I preferred to use the old roads because it would be more interesting and I am too mean to pay the tolls.

Before leaving Komatsu I stopped to fill up with petrol, which was an unforgettable example of the application of Japanese culture to what would normally be a mundane experience. Like most filling stations, this one had attended service, with two young men who smiled and bowed as they waved me into position by one of the pumps. With a slight hint of anxiety one of them looked at me and said “Casha?” when he realized that I was a Westerner, because he was worried that I would offer him a credit card that he could not accept, which would be very embarrassing. I assured him that it was “casha” and he put the petrol in while the other man ran round the car washing all the windows. No tip was expected for this service, and my departure was accompanied by a session of bowing and waving to an almost absurd extent.

Once clear of the coastal town of Kanazawa it was back into the mountains, with miles of hairpin bends and a few tunnels, until I suddenly found myself looking down on a group of ancient thatched houses. This was the Historic Village of Gokayama, a world heritage site and major tourist attraction. It was not short of visitors, but I was guided into a parking space and set off to look round.

The houses were built of wood with steeply pitched thatched roofs in a chalet style, usually with one or two upper stories and were well spaced out between roads and small rice fields. The village was essentially traffic-free, although a few cars were tucked in here and there. Alongside a river and surrounded by wooded hills, it was an idyllic setting but gave the impression of being somewhat over-preserved.

About 15 miles further along the road was another larger and possibly more authentic place called Ogimachi, where I had stayed on my previous trip. Still with wooden buildings, many thatched, the main street is normally open to traffic, and it has a few shops, traditional guest houses and a petrol station. When I arrived the street was closed, with traffic being instructed to take the clogged-up bypass which runs through a tunnel. Vehicles were queueing to get into the other end of the village, apparently for an evening event of some sort, so I had to give it a miss, an unfortunate consequence of the holiday period.

It was still about fifty miles to Takayama through tunnels, past lakes and mountains which meant that it was dark some time before I reached the town. One thing I do not like about Japan is that they will not have daylight-saving time, so in late September it was dark soon after 6pm, very much earlier than at home. I had resolved to avoid driving in the dark, because the road markings and street lighting are poor compared with England, but fortunately the road into the town led straight to the station, which was opposite to the inappropriately-named Country Hotel where I was staying. Even in Japan everybody knows the way to the station.

Takayama is famed for its Old Town with traditional single-storey wooden buildings lining the streets, and the plan for the next day was to have a look round before driving over yet more mountains to Matsumoto. In a street not far from the hotel was the Hida Kokubunji Temple with its three-level pagoda. It seems strange to find a building like that in the middle of a densely built-up area, but it is really only the same as coming across a church or chapel in an English town.

Alongside a river running through the old town I found a morning market, extremely well attended not only by Japanese people, but also Westerners who were presumably on organized tours. It was a few days since I had seen a Westerner, and as I have found before, it came as quite a surprise. After spending only quite a short time among people of oriental appearance I felt as if I was one of them and the Westerners struck me as being different!

The old town appears to be quite authentic, with people living and working in the wooden buildings as they always did, although nowadays geared largely to tourism. Many of them are traditional Japanese guest houses in which ancient customs are upheld, such as sleeping on the floor and communal bathing. Had it not been for the pressures of the holiday period I am sure I could have stayed in one, as I did in Ogimachi on my previous trip, but I doubt whether I could have got in this time without pre-booking, which was virtually impossible from England.

More tunnels, a mountain pass, and a castle challenge

It was the last day of the five day holiday period, and I expected that people would be setting off home to the heavily-populated area in the south. My destination for the day

was Matsumoto, about 70 miles to the east, the other side of some sizeable mountains, and as predicted the road (route 158) was busy but the traffic kept moving quite smartly for about 30 miles. Some distance after a long tunnel it came to a right turn with a toll booth into another tunnel, and all the traffic in front and behind went that way, leaving me driving straight ahead on my own. The road dwindled down into something like a country lane and started climbing, ultimately turning into the Abo Toge pass, one of the best drives I have ever done. When I got to the top it was some time before another car appeared and I began to wonder if the road was actually closed. The descent had a succession of tight hairpin bends that were beautifully depicted on the car satnav, about the only time it had shown anything useful, and eventually the road rejoined route 158 to go through at least another 12 tunnels before reaching the outskirts of Matsumoto.

An essential part of any trip to Japan is a visit to a castle. The ultimate Japanese castle is usually considered to be Himeji, which I had been to previously, but was not on my present itinerary. The best opportunity this time was Matsumoto and as I entered the town I decided to go straight to the castle and to the hotel afterwards, because of the time. Although it is not as 'good' as Himeji, its appearance fulfils most people's expectation of a Japanese castle in every respect.

An essential part of any trip to Japan is a visit to a castle. The ultimate Japanese castle is usually considered to be Himeji, which I had been to previously, but was not on my present itinerary. The best opportunity this time was Matsumoto and as I entered the town I decided to go straight to the castle and to the hotel afterwards, because of the time. Although it is not as 'good' as Himeji, its appearance fulfils most people's expectation of a Japanese castle in every respect.

Just inside the entrance was a notice stating that the waiting time for entry was 20 minutes, and beyond that was a covered area with about 200 people sitting on wooden benches. This was obviously the holiday factor in action, but we were actually taken in in batches of about 100 at a time at 10 minute intervals, so the proverbial Japanese punctuality was upheld. As soon as we got through the door we were required to remove our shoes and given a plastic bag to carry them in. At Himeji visitors were provided with slippers which were a source of some amusement because none of the Western men could get into them. The largest were about English size 7, and I take 9 (EUR 43), so I was left with my socks. At Matsumoto no slippers were provided, so it was socks or bare feet anyway. This might not have seemed too bad, had the floors and particularly the stairways not been so highly polished.

Progress was painfully slow, as the vast crowd was forced onto a single line that snaked its way up five flights of steep slippery stairs to the top of the building and down again. According to a notice the steepest flight was at an angle of 61 degrees from horizontal with a rise of 41cm between the treads. In Britain I am sure this would have been banned by the Health and Safety Executive, and I was astonished by the way the Japanese people, many of them elderly, tackled it with great determination. Going down was more difficult than going up, and surely they can't all have been in the navy?

Various historical items, mainly weapons, were on display as we went round, but the most memorable parts of the tour were the views from the upper floors, which were superb. From the castle it was only a short distance to the centre of the city, which comes across as quite European in character. The one major difference from most Japanese city centres is the absence of the incredibly ugly overhead cables that ruin almost every photograph that you try to take anywhere else.