Istanbul, Turkey 2016

CLICK ON PICTURES TO ENLARGE

Istanbul 2016

My trip was to be a long weekend with three complete days in the Istanbul area. For me Istanbul has always conjured up an image of a dramatic and exciting city at the junction of Europe and Asia, thronging with secret agents and spies. This was reinforced by Wikipedia, which lists 89 films and hundreds of books as having been at least partly set in the city. It has long been of great political and religious significance as a leading base of the Ottoman Empire, to say nothing of the improbable fact that there are four car museums in the area.

For the first night I reserved a room at the Hilton Garden Inn Atatürk hotel, which was about two miles from the airport, and I had hoped to arrive before dark. By the time I got to the car rental office it was dark, which makes it more difficult to check the car for defects. The booking was made through a broker highly recommended by Which? called Zest Car Rental, who offer a selection of providers at various prices. I have never believed in stinting in this respect because I think it is why so many people have trouble, but in this case I chose a Hyundai Accent from one of the cheaper local firms called Erboy. They always reserve the right to substitute what they consider to be an equivalent car and I finished up with an Opel Corsa (Vauxhall Corsa at home), a car that I particularly dislike. An immediate problem was that the driver's seat was too low and not adjustable for height, which I solved by making a cushion out of the spare clothes which were in a strong plastic bag in my case. Far from ideal, but I was not going to be driving any great distance and have never bothered much about ironing anyway.

After studying several maps of Istanbul I realised that the local road system is extremely complicated, with a vast number of one way streets and mini Spaghetti Junctions everywhere. The Turkish language is not at all easy, and street names are hard for a non-speaker to remember. As usual I had street level maps in my tablet and phone, which proved to be absolutely indispensable, as they can be expanded to show junction layouts in great detail. Even so I managed to get lost in the two miles from the airport to the Hilton Garden Inn Atatürk Hotel.

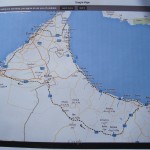

The next morning I could fully appreciate the magnificent view from my room, which was on the 14th floor. Somehow I had imagined that Istanbul would be flat, but in fact it was built on a range of hills, divided by two major waterways. One is a wide estuary called the Golden Horn leading into the Bosphorus Strait, which runs northwards from the Sea of Marmara through to the Black Sea, thereby separating Europe from Asia (see map). About two thirds of the city is in Europe and one third in Asia, the total population being over 14 million, which is greater than any other city in Europe. Despite its size, it is not the capital of Turkey, that honour going to Ankara, over 200 miles away.

My first port of call was to be the Mehmet Arsay Classic Car Collection, which after a great deal of research I had worked out was on an industrial estate in the north of the city, but I had serious doubts whether it still existed. It appeared to be at the end of a long narrow shopping street where I stopped at a café for breakfast because I could not afford the hotel’s prices. No one in the café spoke English and I finished up with a pastry filled with cold meat instead of the jam that I expected. Just like France.

The industrial estate was large and modern with no signs and the man in the gatehouse did not speak English. However, when I showed him the address of the museum there was a glimmer of understanding and after speaking to someone on the phone he directed me to the far end of the estate road, where I could just see a man waving his arms. He led me to the museum building, which only had a tiny nameplate on it and guess what – he spoke no English at all, but was clearly passionate about the exhibits in his charge. They were one man’s personal collection, about eighty cars, fifty per cent of them American and all in absolutely perfect condition. There was no charge for the visit, and despite the language problem the curator and I seemed to part as very good friends, typical of the camaraderie that exists in the classic car world.

My next stop was to be the Rahmi Koç Museum, a large transport museum about six miles away, close to the eastern bank of the

Golden Horn. Much of the route was on an elevated motorway, which afforded marvelous views of Istanbul’s astonishing skyline with mosques and other notable buildings in all directions. The bridge over the estuary consisted of several separate carriageways, and I shall never know how I managed to get into the correct one for the slip road the other side, but somehow it worked out. The traffic was fairly heavy and the general standard of driving fell well short of that in Britain, although I have seen much worse elsewhere.

Apart from a large number of motor vehicles, including some Turkish cars, the museum had trains, ships and aircraft. In the main car hall was a photographer taking pictures of a just married couple still in their wedding finery. The bride was draped in various poses across the cars and the absence of any other members of the wedding party suggested that it was a staged photographic session for some publicity purpose.

My night stop was to be in a small resort called Kilyos on the Black Sea, about 17 miles north of Istanbul. This might not sound very far, but the route was quite complicated and I expected it to be slow going. From the museum I planned to drive about 4 miles eastwards on the motorway and then turn northwards and take an ordinary road through a town called Maslak. Unfortunately I missed the turning on the motorway for Maslak, and found myself heading inextricably at 70mph for the famous Bosphorus Bridge, the main road link between Europe and Asia. The bridge has an electronic toll system, and the penalties for non-payment are said to be quite severe. I had asked the people in the car hire office about this, but due the language problem I was still not clear about the procedure, and whether the car had a transponder. Anyway, as I hurtled into Asia there was nothing I could do but take the first exit, which led me round in a circle and back on to the bridge in the opposite direction! This must have been one of the briefest stays in Asia that anyone has ever had, although there were some good views from the bridge. At the time of writing no one from Interpol has knocked on my door to demand payment.

As expected, the route through Maslak up to a town called Sariyer was slow going, but once clear of the built-up area the scenery was quite pleasant and I reached Kilyos late in the afternoon. The Yuva Hotel was not very good, and had few other guests. The whole resort was extremely quiet and I think there were more restaurants than visitors. The short promenade and beach area had a run down appearance with cracked concrete and dilapidated buildings, which suggested a long term decline rather than just the end of season effect.

The plan for the Saturday was to drive back to Istanbul along the west bank of the Bosphorus, calling in at a car museum just south of Sariyer, and reaching the Ramada Grand Bazaar Hotel in the middle of the city by early afternoon in time to go to the Bazaar, which is not open on Sundays. The museum was absolutely superb, in the form of a traditional American diner, with dozens of working neon signs, petrol pumps and a collection of iconic cars, all in perfect condition. Everything was spotlessly clean, and the only member of staff who spoke English told me that it was, again, all one man’s property. It was quite obscurely situated in the middle of a maze of narrow suburban streets and has limited opening hours, but there were a few other visitors.

The road alongside the Bosphorus passed through a number of busy resorts and under the Bosphorus Bridge, with a scenic backdrop the other side of the strait. Eventually and inevitably I hit the city centre traffic on the approach to the old bridge over the Golden Horn and it became very slow going. All the books advise against driving in central Istanbul but I got to within a short distance of the Ramada without too much trouble. Then the problems started. The hotel was in the middle of a network of mainly narrow one-way streets, some of which were blocked off with rising bollards. The streets that I could get into were obstructed by vehicles loading and unloading, with rampant double-parking everywhere. After about an hour I managed to park about 200 yards from the hotel and asked a taxi driver how I could get to it. He said “You can’t, the streets are blocked off from 10.00am to 8.00pm. We can’t even get through with taxis”. It was hard to believe such idiocy, but when I walked to the hotel they confirmed what he had said.

On the booking form the hotel claimed to have “private parking on a site nearby”, which is the reason why I chose it. It turned out that this parking was also within the closed off area, and they sent a man out with me to find another car park. After about a further hour of struggling around the congested streets we gave up and I had to leave the car in the street until 8pm. The hotel people were embarrassed about this situation and gave me an upgraded room, free breakfasts, and free parking (when I could get to it) as compensation.

After all that I still had time to walk to the Grand Bazaar, which was open until 7pm. The Grand Bazaar dates from 1455 and is one of the oldest and largest covered markets in the world, incorporating 61 streets and over 4000 shops. It receives between 250,000 and 400,000 visitors daily and in 2014 was listed as number one among the world’s most visited tourist attractions. As it is within the old walled city it can only be entered through massive gates that are closed outside trading hours.

The streets are narrow and pedestrianized with some hills actually inside the Bazaar. All the usual merchants are there, offering food, clothes, and household goods, with areas devoted to jewellery, silver and rugs etc. The famous quality brand names are in evidence, but at prices that are not on the same planet as those for similar articles in London or Paris, and it is only possible to draw one conclusion. Obviously there are a vast number of shops selling the same things, and competition is intense, with haggling being an essential part of the purchasing experience. Some distance away is a separate Spice Bazaar that I did not get to.

It was dark when I got back to the hotel and the bollards were down, so someone came with me to collect the car and put it in the proper underground car park nearby, where I left it for two nights.

I had reserved the next day, Sunday, for sightseeing on foot. Fortunately the weather was perfect as I walked along the main tram route to the district called Sultanamet which contains three of the most important sights including the Blue Mosque, which is not the largest in Istanbul, but is said to be the most photogenic. Everywhere you look there are mosques, and the skyline is dominated by them, but I was astonished to learn that there are actually over 3000 in the city, though not all are still active. Many mosques are not open to non-Muslims, and the Blue Mosque was the first one I had ever been into. Subject to certain rules regarding dress (e.g. no shorts or sleeveless tops, shoes must be taken off) it is open to everyone. It is one of the most popular tourist attractions, and I was surprised to find that at 10.00am on Sunday morning there was no queue, which might be a consequence of foreigners being deterred by the coup. Carrying my shoes in a polythene bag (provided, with no 5p charge!), I entered through a side door reserved for visitors.

The interior was beautiful without being extravagant or opulent in the way that many great buildings are, being decorated with a vast number of tiny tiles, predominantly having a bluish tint, hence the name. Stained glass windows were very much in evidence, reaching high up towards the dome, which was lined with the tiny tiles. As always in such buildings, one can only wonder at how people carried out such labour-intensive work in what must have been dangerous and difficult conditions.

The floor was carpeted and there was very little furniture, appropriate for the style of prayer in the Muslim faith. Photography was allowed and entry was free.

On a par with the Blue Mosque was the next building on my itinerary, the Aya Sofya. Originally built as a church by Emperor Justinian in 537 and converted to a mosque in 1453, it eventually became a museum in 1934. I did not go in, but externally I thought it was just as photogenic as the Blue Mosque.

On to the Basilica Cistern, a huge subterranean reservoir built in 532. It has 336 stone columns, all 9 metres high, many taken from ruined temples elsewhere and standing in shallow water which is home to carp and goldfish. The whole place is dark with discrete orange lighting and on entering from bright sunlight it is difficult to see anything for a while. The photographs, taken without flash, give a realistic representation of the light level when seen from the elevated walkways. Major items of interest are enormous stone Medusa heads at the foot of two of the columns. They were deliberately placed with one is on its side and the other upside down, although no one knows why.

As I walked through the streets towards the waterfront I was accosted several times by men who either asked me where I was from or just addressed me in German. They always started off very chatty, saying that they had friends in Liverpool or somewhere when they realized that I was English, but worked their round to asking me to go to their carpet shop. After a while this becomes very annoying, although it was nothing like as bad as in Morocco or Cuba.

The waterfront, in the area where the Golden Horn runs into the Bosphorus, was exactly the sort of exciting place that I had imagined Istanbul to be. The long quayside was thronging with people, against a backdrop of frantic activity by ferries and river cruisers, mainly connected to various ports on the Golden Horn and the Bosphorus, but some going as far as the coasts of the Black Sea and Sea of Marmara.

I walked over the Galata Bridge across the Golden Horn to Beyoğlu, the northern part of the city centre. The bridge was lined on both sides with fishermen who, despite the reputed pollution of the local waters, seemed to be doing quite well with their catches. The view from the bridge was superb in all directions, with hillsides covered with densely packed ancient buildings, including innumerable mosques and, of course, that unforgettable skyline.

Leading up the steep hill from the bridge is the main street of Beyoğlu, called İstiklal Caddesi, lined with imposing 19th century buildings, many of which are now shops and cafés. This street went on and on, which I simply could not, and eventually I turned back and returned to the waterfront.

My route back to the hotel took me, perhaps unwisely, through an area of deserted streets past the closed Grand Bazaar, where I could have been mugged with no hope of anyone coming to my defence. It is all too easy to wander into such situations, and I resolved, as I have done many times before, to be more careful in future.

On the way back to the airport the next morning I took the main road along the coast of the Sea of Marmara, with its hectic traffic and empty beaches. Returning the car was a chaotic procedure, with the car park barrier refusing to lift when I arrived, and no one in the Erboy office, but I eventually sorted it out.

A few points about Istanbul.

Far fewer people than I expected spoke English, but many spoke German, probably because a lot have worked there

Public toilets are fairly easy to find, although some are not exactly salubrious.

The city centre congestion is dreadful, largely as a result of bad driving and poor traffic management. Light controlled junctions are continually blocked by crossing traffic and double-parking is rife.

Accommodation and restaurant meals are not particularly cheap and overall I thought it was more expensive than some other southern European countries.

Not long after my visit thousands more government employees and many journalists were dismissed, indicating that the country might not be as stable as it appears on the surface.

India 2016

CLICK ON PICTURES TO ENLARGE

INDIA 2016

Chaotic, filthy, dangerous, everything I had hoped for.

Some people have been to over 100 countries. All I have managed is a mere 45 and I have always thought I could not call myself a proper traveller until I had been to India. In particular I wanted to experience driving in India first hand, and some people said it would not be possible to apply my usual holiday format to the country, i.e. booking flights and hotels and then travelling around alone by self-drive hire car. It is not uncommon for people to do motorcycle tours on their own, but self-drive car hire is very difficult to arrange and the people I knew who had been to India were aghast at the idea. The more usual procedure is to hire a car with driver, which did not appeal to me at all.

The guide books all have pages about potential health problems, and everybody I spoke to at home seemed to know somebody who had been to India, caught some ailment, and never been the same again. It was slight consolation that at the age of 77 the length of time for which I would never be the same again would probably not be all that long. At the very least I expected to have the famous 'Delhi Belly' which practically everyone from Britain gets, but on the advice of a friend I decided not to eat meat. The books also make a big issue of the need to avoid insect bites, especially with regard to mosquitoes, although the area I was going to is considered to be low risk for malaria. The best repellants are those containing DEET, which I find very unpleasant to use but I took an ample supply with me and also got my vaccinations updated. It is generally considered that it is not safe to drink the tap water unless you can boil it and if you buy branded bottled water it is important to check the seal, because it is not unknown for empty bottles to be refilled with tap water. I took some water purification tablets, just in case, but where possible made tea or coffee in my room with boiled water.

For my base I chose Cochin (Kochi), Kerala, in the south eastern corner of India because there were cheap convenient flights with Emirates from Gatwick, and it is a small city compared to Mumbai or Delhi. My flight arrived at Cochin at about 8.00am, and I was surprised to find how well organized the airport was. I was expecting to be besieged by taxi drivers and money exchange touts, as Indian currency is not convertible, which means that you have to change money on arrival. In fact there were several bureau- de-change and a counter for pre-booked taxis within the non-public part of the airport, which means that everything was sorted before I reached the exit. The pre-booked taxi voucher was for a particular car and an Indian bloke from Brighton helped me to find it in the crush outside. The 20 mile journey to the Grand Hotel was an opportunity to study the driving, which I felt that I would be able to cope with, and contrary to what I had expected the driver was actually quite good. Nevertheless, in the back of the car, with the bumpy roads, I was starting to feel sick by the time we got to the hotel which confirmed that the 'car with driver' option was not for me.

In the past I have generally been good at estimating in advance the amount of ground I would be able cover during my stay in foreign parts, but India was too much of an unknown quantity to risk booking any accommodation apart from the first two nights and the last night.

The Grand Hotel Ernakulam, which I had chosen from Booking.com, was traditional and not very smart, but turned out to be used by some British tour operators. After 3 or 4 hours sleep I ventured out for a walk round and was immediately struck by the intense heat, which was to become an issue affecting my activities for the whole trip. I was expecting it to be tolerably hot, maybe around 30°C (86°F), but in fact excepting in the mountains it was well in excess of that. On the day I was in Calicut (Kozhikode) it was 38.5°C (100.7°F), the highest temperature ever recorded there, and we are talking about Southern India. Under such conditions I cannot walk very far and am stuck either in my air-conditioned accommodation or air-conditioned car.

Ernakulam is the commercial centre of Cochin, and the hotel is in MG Road, the main artery running through the town. I thought it was rather strange that an Indian town would have its main street named after an old English car company, but quickly discovered that MG stood for Mahatma Gandhi, and it seems that every town in the country has an MG road. It was all rather scruffy, with lots of rubbish around and difficult walking on the rough pavements, which is what I had expected. Just out of interest I wandered through to the main railway station to find the platforms crowded, although there were no people hanging on to the sides or roof of the carriages.

Fort Cochin

The next day was Sunday and I had planned to spend it looking round the area, with a ferry trip across the harbour to Fort Cochin, a former British army base. Luckily the ferry terminal was easy walking distance from the hotel and it was only a short wait before the next sailing, which, judging by the look of the vessel, might well be its last. I could see the Daily Telegraph headline 'India Ferry Sinks - 60 dead'. At least there were plenty of lifejackets, about five for each person on the ferry, so I was planning to tie some together to make a raft as the boat went down. Like the local buses, it had no glass in the windows, so it would be easy to get out.

At Wilmington Island, a naval base, the ferry stopped briefly at a jetty in front of a row of big colonial-style detached houses, before continuing to Fort Cochin. As soon as I set foot on land I was surrounded by tuk-tuk drivers wanting to show me the sights. I insisted that I wanted to walk but one of them followed me along the road until I turned off into an alley too narrow for his vehicle. Fort Cochin is a maze of narrow streets and alleys with a long main street lined with small shabby shops and cafes. In one place I came across a bowl of rice placed on the edge of the pavement, and as I approached a large rat came out of a hole at the side, nibbled at a few grains of rice, and ran back into the hole. I could only think that either the rice was poisoned or the idea was to attract the rats out into the open where cats could get them. In one

dingy cafe I asked for a cup of coffee which proved to be so strong and sweet as to be almost undrinkable, and this turned out to be the norm for coffee in Indian cafes.

The intention was to walk along the main street to the beach, and follow the shore back to the ferry terminal, but unfortunately I turned the wrong way when I left the café. By the time I discovered my mistake I did not have enough energy to walk the whole length of the street again, so I hailed a tuk-tuk and said to the driver “Straight to the beach, please”. Totally predictably he started to take me on a tour of the sights, which weren’t very interesting. Every time he started to deviate I said loudly “To the beach please”, and eventually we got there.

This was definitely not a Blue Flag beach, with quite lot of rubbish around and no one in the water, despite the heat. It is likely that the water was too polluted from the surrounding residential and industrial areas. A stretch of the beach was given over to fishing activity, including the Chinese fishing nets, for which Cochin is famous. These consist of nets up to 20m across suspended from wooden beams so that they can be lowered into the water, counterbalanced by heavy stones attached to ropes. It takes several men to operate each net, and although they are a major tourist attraction the long term viability of such a labour intensive process is in doubt.

After surviving the ferry trip back to Ernakulam I walked along the busy promenade on the way back to the hotel. All day I had seen only a handful of Westerners, which I found surprising considering that it is supposed to be a tourist area.

The first thing I did the next morning was to carry out a brief health check. Did I feel ill? No, I felt fine. Insect bites? A few small ones, and one big inflamed lump on my thigh with a red streak about two inches long running away from it. This would have to be watched, as I thought it was possibly a sign of infection or blood poisoning.

Preparing to face death on the road

My car was due to be brought to the hotel at 10.00am and I was looking forward to it with some trepidation. As previously mentioned, self-drive hire is very difficult to arrange in India, because most of the big international companies have given up doing it due to bad experience, and now only offer car with driver. Eventually I had found on the internet a firm called Kerala Self Drive Car Rentals who were prepared to do it and seemed quite good to deal with. They would not accept a credit card as security, and required a cash deposit equivalent to $1000 (£720 at the time), which needed a certain amount of trust.

At 9.30am Mr.Manu arrived in the hotel car park with a silver Hyundai I20 Sportz in quite reasonable condition. He insisted that I take photographs of all the minor defects, which took a while, but the car had good tyres and all the essentials seemed to be in working order. He required copies of my passport, Indian visa, driving licence, international driving permit and payment for the rental as well as the cash deposit. Nevertheless, I felt that he was risking more than I was.

Before going any further I should say a bit about the make up of traffic in India. Notionally Indians drive on the left, but notionally is as far as it gets. In reality they drive all over the road, and you meet people coming towards you on your side of the road much of the time.

Cyclists are in a minority, most having been killed I would imagine, and the remaining ones wobble around on basic upright bikes. Motorcycles and scooters are the staple form of private transport, in numbers that far exceeded anything that I expected or have seen anywhere else excepting Taiwan. Many of them travel quite slowly (20 – 25mph) carrying up to five people, though usually one or two. They are mainly of Indian manufacture and up to 250cc, larger bikes being the locally-made Royal Enfields or Japanese models. Some are ridden fast, but it is unusual to see really high speeds. It is common for motorcycles to be ridden along the side of the road against the main flow of the traffic.

What we call tuk-tuks (Indians call them auto-rickshaws) and their commercial variants are everywhere in towns and sometimes found on main roads out in the countryside. They have tiny engines which can push them along at about 25mph on the level, and as soon as they come to a hill their speed drops dramatically. They are driven very aggressively in towns.

India still has a relatively low level of car ownership and as in all developing countries ownership of an expensive car,

especially a German one, carries with it an automatic expectation of priority on the road. Taxis are driven the same as taxis everywhere. The Hindustan Ambassador, based on the 1955 Morris Oxford is still around but in rapidly diminishing numbers, production having ceased in 2014. Most cars are of Indian or far eastern manufacture, European makes being rare. The Tata Nano, the world’s cheapest proper car at about £1700, has not been the success that was hoped for but is around in significant numbers.

Trucks travel as fast as they can. When heavily laden this may mean 15 – 20mph, but at other times they go very fast, forcing their way past everything in sight, and it is best to keep out of their way. In my experience bus drivers are the most ruthless, indulging in crazy overtaking manoeuvres , in which I was almost pushed off the road several times.

In towns and on many country roads, although it seems very hectic, the actual speed of the traffic is quite low, because there are so many slow-moving vehicles. In towns a few junctions have traffic lights, or are controlled by a police officer, but a lot are completely unregulated. Watching the traffic negotiating an unregulated 4-way junction is an education, and even more so when you come to do it yourself. The trick is to just keep moving, and somehow you come out the other side without really knowing what happened. I quickly realized that Indian drivers work on the basis WHEN IN DOUBT – GO! Speed limits, where they exist, are completely ignored.

In towns and on many country roads, although it seems very hectic, the actual speed of the traffic is quite low, because there are so many slow-moving vehicles. In towns a few junctions have traffic lights, or are controlled by a police officer, but a lot are completely unregulated. Watching the traffic negotiating an unregulated 4-way junction is an education, and even more so when you come to do it yourself. The trick is to just keep moving, and somehow you come out the other side without really knowing what happened. I quickly realized that Indian drivers work on the basis WHEN IN DOUBT – GO! Speed limits, where they exist, are completely ignored.

Horn blowing is incessant, especially by truck drivers. Many slow-moving vehicles have a sign stating SOUND HORN on the back, which seems to have no effect whatsoever.

The people who come out worst in all this are pedestrians, who are, at best, poorly catered for. In towns pedestrian crossings do exist, consisting of a faded sign on a post and some barely visible stripes on the road, but no one actually stops to allow people to cross. If you wish to cross you have to wait for a small gap between vehicles, stride boldly into the road holding up your hand, and any vehicles aiming directly for you will usually slow down enough to avoid hitting you. You then just have to hope that the next vehicle aiming for you will do likewise. The ideal situation is to find two or three big blokes waiting to cross, and go level with them, using them as a sort of human shield.

Into the fray

Starting off in an unfamiliar car in the main street of a busy foreign town is never an ideal situation, and I must admit that as I emerged from the car park on to MG Road I was not brimming with confidence. My original itinerary was to drive westwards to Munnar, a former British hill station and tea growing area, but I was not sure what the road conditions were or how long it would take, so for the first day I decided to take a more straightforward route to the north, which would give me a wider choice of places to stop for the night.

For route planning I had an A4 colour photocopy of a map at about 22 miles to the inch (1:1,400,000) and for navigation I used offline HERE and BING maps in my Windows phone and offline NAVMii in my Android tablet. These did not tell me which way to go but ensured that I could always find out where I was.

The driving on National Highway 17 was far more difficult than I expected, with lots of slow-moving vehicles all over the road in both directions. I made a note at the time “heavy traffic and lunacy”. After a couple of hours I stopped for another awful coffee and decided to aim for a town called Thrissur which according to my guide book was a reasonably pleasant place.

Thrissur

By the time I got to the centre of Thrissur I was shattered, partly from the driving and partly due to jet-lag from the 6½ hour time difference between home and India. The first hotel I saw was a big place called the Ashoka Inn and the car park attendant guided me into a space. He had a big moustache and gave the impression of being an ex-military man, which I later discovered seemed to apply to all the hotel car park attendants that I came across. He did not appear to speak much English, but said “First floor” and took me up to a room where a conference was in progress. This might have been an opportunity to learn something useful, but I chose to give it a miss, booked a room and went out for a walk.

Opposite to the hotel was an area of rough land with some market stalls and a bus station incorporating a shopping parade with a dense mass of motorcycles parked in front of it. Piles of rubbish everywhere and muddy puddles which I thought were probably an ideal breeding ground for mosquitoes and other undesirable creatures, an assessment that later proved to be correct.

The hotel car park attendant had told me to go to the Mall of Joy, which turned out to be an air-conditioned upmarket clothing centre, a world away from street outside where the temperature was 38⁰C (99⁰F) which I could not tolerate for long. It was hardly my scene, but the shops in the Mall offered a vast range of beautiful silks and fabrics in the traditional Indian style as well as modern clothing.

Back to the hotel and after a meal in the vast restaurant I went out for another walk around. By now it was dark, but I will walk anywhere in the dark unless it is obviously dangerous, as in much of the USA. The street lighting in Thrissur is poor as was the condition of the pavements, but I did not feel that there was any great threat of being mugged. In the unlikely event that the people in the Foreign Office Travel Advice section read this they will probably take my passport away. Anyway, I did not have the energy to walk very far.

Back to the hotel and after a meal in the vast restaurant I went out for another walk around. By now it was dark, but I will walk anywhere in the dark unless it is obviously dangerous, as in much of the USA. The street lighting in Thrissur is poor as was the condition of the pavements, but I did not feel that there was any great threat of being mugged. In the unlikely event that the people in the Foreign Office Travel Advice section read this they will probably take my passport away. Anyway, I did not have the energy to walk very far.

Moving on

With the day’s experience behind me I could now plan ahead, and decided to aim for Ooty, an old hill station in the state of Tamil Nadu, at one time under British occupation. Like many places in India, Ooty has several different names, the most formal one being Udhagamandalam, and its elevation of 2,240m (7350ft) meant that it would certainly be cooler than the areas I had been to so far. The most direct route was via Coimbatore, a thriving city of 1.6 million people, and I did not realise what I was letting myself in for.

The morning health check was good and the bite with the red streak showed signs of receding. My notes at the time say “crazy drive out of town” (Thrissur) and it was slow going to Shoranur. The road then became much less busy and quite scenic to Palakkad, where it joined National Highway 47, a modern dual carriageway toll road, though with its share of intersections and some slow traffic. The road was still under development and eventually on the approach to Coimbatore dwindled down to a narrow strip of tarmac wending its way for about a mile through a building site.

Coimbatore

At 4.00pm I reached Coimbatore. My notes say “Madhouse. Worst ever traffic nightmare”, this coming from someone who has driven into Moscow and through the centre of Seoul. My phone map showed some hotels near the end of a bridge leading to the town centre, and through the chaos I glimpsed one called the Kooloth Lake View Residency, much less smart looking than its name suggested, but by then I would have gone for sleeping over a rope in a dosshouse just to escape from the traffic. In the end I had to park and walk to the hotel to find the entrance and the underground parking set up.

A steep ramp led down into the car park and the obligatory man with the big moustache also had an ear-piercing whistle which he blew repeatedly while I was trying to make an eight-point turn so that I could drive out going forwards, making the task considerably more difficult than it should have been.

For the sum of 1400r (approx. £16.50) I was given an en-suite room on the corner of the Kooloth Lake View Residency with large windows facing along the main street one way and down on to it the other. Coimbatore is the sixteenth largest city in India, its main industries being engineering, textiles and electronics, and certainly gave the impression of being a hive of activity.

The road in front was a dual carriageway, actually part of NH47, and when I went out to look round the town I was surprised to see three large cows lying in the road up against the central reservation. I had passed a few cows on the road on the way from Thrissur, but these were in an exceptionally noisy and exposed position, and it is hard to understand why they didn’t settle down in one of the quieter side roads instead of the main traffic stream.

The hotel didn’t do food at all, but I found a vegetarian restaurant in the main street for my evening meal, after which I looked at the shops. The range was enormous, including an up market clothing centre like the Mall of Joy. Running parallel to the main street was a pedestrianized lane full of shops, and off that a souk (market). The prices were by our standards very cheap and as far as I could see all this was aimed at local people, because there were no obvious tourists in the place apart from me. The quantity of beautiful silks and fabrics, especially for women, was mind-boggling.

When I got back to my hotel room the first thing that struck me was the noise. It must have been the noisiest hotel room in the world. As always, I was very tired and with great reluctance I put in the ear plugs that I take to wear in cheap American motels. They are quite uncomfortable, but I eventually fell asleep until I was woken by a truck sounding its horn under the window at 3.00am. In fact the noise was incessant, especially the horns and brakes of the trucks as they approached the adjacent junction, and I must have somehow slept through it for a long time, but once awake there was no prospect of getting back to sleep.

To the mountains

By 7.00am what was left of my nerves after a few days in India could take no more so I packed and left the hotel. The prospect of emerging into the Coimbatore rush hour traffic was not enchanting but anything was better than that room. The main route out of this industrial city entailed driving through a mass of motorcycles going in all directions, and I don’t know how I did it, but by the time I got to Mettupalayam things had calmed down a bit. From Mettupalayam to Ooty, via Coonoor , was a continuous climb for 30 miles, a single carriageway road consisting entirely of sharp or hairpin bends joined together with no straight bits excepting through Coonoor itself.

Ooty is a much favoured place for people to escape from the high summer temperatures, and has been developing quite fast for a long time, which means that there are lots of trucks slogging up the mountain carrying building materials. Their speed is such that it is unrealistic for vehicles operating to a time schedule, such as taxis and buses, to wait behind them, so if there is the slightest chance of getting past they go. Europeans see this as highly reckless, dangerous, driving, but it is just how things are done, and time and time again you see vehicles coming face to face on bends. Somehow some space miraculously appears and a collision is avoided. People who have ‘car with driver’ often plead in vain with the driver to stop indulging in such practice but he or she just carries on because it is the norm. I overtook when I could, but I could not bring myself to launch into a blind bend on the wrong side of the road, which sometimes made me unpopular with the people behind.

The scenery was excellent but there were few places where it was possible to stop for photos and it was rather misty. Other impediments to progress were roadworks, landslides, breakdowns, cows and little grey monkeys running around on the road.

The scenery was excellent but there were few places where it was possible to stop for photos and it was rather misty. Other impediments to progress were roadworks, landslides, breakdowns, cows and little grey monkeys running around on the road.

Ooty

Ooty is spread over a large area of high ground, with tea plantations and vast developments of bungalows, many of them fairly recent. The road from Coonoor drops down towards the centre with a string of hotels on both sides, and I chose a modern one called the Hornbill Residency which had a sign outside listing a range of facilities including Doctor on Call and WiFi. So far I had not been able to make the latter work with my phone or tablet anywhere in India, and I concluded, rightly as it turned out, that there must be something wrong with my set up at home.

The temperature in Ooty was much cooler than everywhere else I had been so far, making it really comfortable for walking about. Most of the shops were straight out of the 1920s and 30s, a few having traditional English family names such as Higginbothams book shop, and I spent quite a bit of time poking about in the back alleys. Ooty is an attractive place and I should have stayed longer there, although it was quite cold in the night.

Another health check the next morning and surprisingly all seemed to be well. A few minor bites, but the one with the red streak had almost disappeared. So far I had seen very little of the inefficiency for which India is noted. In fact, on the whole most dealings I had with people had been easy and straightforward by any standards. It is true that I had difficulty in understanding some people and they had difficulty in understanding me, but that was purely a linguistic matter. However, the only way to get breakfast in the hotel was to have it brought to my room, which proved to be a logistical challenge. From ordering it at reception to actually getting it took about an hour, during which staff came to my room several times to confirm what I wanted, each time with slight variations on what was actually available. By the time it came I was on the point of giving up.

To the coast

Most of the traffic to Ooty goes out the way it came in, via Mettupalayam, but as I was essentially on a circular tour I left the town in the other direction, towards Gudalur. This is a mountain road similar in character to the one the other side, still with the endless bends but with much less traffic and, of course, I was going downhill. Within a short time I came round a bend to find the road completely blocked by two buses coming towards me side by side. Exactly as I described earlier, some road space mysteriously appeared and there was no crash. However, the bully-boy buses going in my direction were a problem for a long way, and my notes say “lot of near goes”. The scenery was brilliant, when I could look at it.

Somehow at one point I got lost, and although I quickly discovered where I was, I was about 15 miles from where I was supposed to be. There were some police or military check points, and I was just about to be stopped when the officer realized that I was a foreigner and waved me on. In most countries the foreigners are questioned and the locals waved through, but it seems that India is different. The checkpoints may have had something to do with the state border between Tamil Nadu and Kerala.

My target for the day was Calicut (Kozhikode), a major city on the coast of Kerala, and I found quite a smart hotel without too much trouble. Just as I got to the reception the lights went out and within a short time the hotel’s own generator kicked in. I asked if this was a common occurrence and was told that it was rare, which was belied by the number of businesses around with their own big expensive generators. The central area of Calicut is quite Western in character, clean and tidy with modern shops, including an unbelievable number selling phones and associated products. Also plenty of decent restaurants, but I stuck to my usual vegetarian fare which had served me well so far on the health front.

The next morning the heat was intense, and I had to abandon an attempt to walk the half mile to the beach after breakfast. Later in the day the temperature was to reach the highest figure ever recorded in Calicut, at 38.1⁰C (100.58⁰F). I drove through to the beach, and was rather surprised to find it almost completely deserted. It was just too hot to sit around, so I carried on down the coast road towards what appeared to be a resort called Ponnani where I thought I might stay the night if I could find a hotel. It turned out to be a very poor run down area with a couple of ‘hotels’ that fell far short even of my undemanding standards. After messing about for a long time I finished up driving down to Guruvayur, a spa-like town with lots of decent-looking hotels.

The first one I came to had no vacancies, and in the second one about ten young men walked up to the reception in front of me. The man at the desk asked what I wanted, and when I asked if there were any rooms this was greeted with considerable merriment by the other group. The man said they were fully booked, and then I suddenly remembered reading about Guruvayur.

The town is centred around one of the most famous Krishna temples in India, to which people come to worship from all over the country. In particular it sees up to around 200 weddings every day, and the hotels are fully booked for months in advance. The young men I encountered probably thought I had come to the town in search of a bride!

Thrissur again

It was too late in the afternoon to for there to be any hope of finding a hotel or a bride, so I decided to push on to Thrissur, where I could be sure of finding good accommodation. I suddenly discovered that I had finally come to terms with Indian driving and made really good progress over the thirty mile journey, arriving well before dark. At the Ashoka Inn I was greeted like James Bond returning to one of his old haunts. “Good Evening, Mr.Bond. How nice to see you. Your usual room?” Well, not quite, but the staff ran around as if I was going to buy the place and I concluded that maybe I was tipping too generously.

During my previous brief stay in Thrissur I had completely failed to find the city centre or anything very interesting but this time I was better organised. On the way to the centre the street was lined with market stalls, apparently for the locals because as elsewhere I was the only tourist. And what about the beggars for which India is noted? They were there, though not in the numbers that I expected. Most of them were very old, many crippled and emaciated, looking as if they had just been released from Belsen. Most developed countries have beggars but these people were in a different order of wretchedness from those on the streets of London or Brighton. India is not sub-Saharan Africa. It has nuclear energy, space rockets and thriving industry which is investing all over the world, so perhaps it is time for this problem to be faced.

The town centre was quite lively with plenty of shops and restaurants, with a big choice of vegetable dishes, but strangely I ran into a serious language problem in the first place I tried. I don’t think they were being difficult, I think there really was no one who spoke English and ultimately a satisfactory meal was produced. It just seems that Thrissur is not well set up for foreigners.

By now I had come close to using my 700km distance allowance with the car, after which a high kilometre charge would become payable, so I decided to take some photographs in Thrissur the next morning and then go back to Guruvayur to look at the temple. On the way back to the hotel at about 11.00am after the photo session I was walking across the waste ground near the bus station when a large rat ran in front of me and hid under a bus. About 50 yards further on were piles of rubbish each side of the path and I looked down to see about six rats on one side and three on the other.

As I drove into Guruvayur I passed the only elephant that I saw in India. It was highly-decorated, with two young men riding on it and appeared to be accompanying a band with about a dozen members. The main street in Guruvayur was also highly decorated with a permanent roof supported by steel columns. This led to an area in front of the temple where a large number of people were waiting for a ceremony of some sort to begin. Non-Hindus are not allowed into the temple and people were looking quite hard at me, so I decided to move on.

As I drove into Guruvayur I passed the only elephant that I saw in India. It was highly-decorated, with two young men riding on it and appeared to be accompanying a band with about a dozen members. The main street in Guruvayur was also highly decorated with a permanent roof supported by steel columns. This led to an area in front of the temple where a large number of people were waiting for a ceremony of some sort to begin. Non-Hindus are not allowed into the temple and people were looking quite hard at me, so I decided to move on.

Back in Thrissur in the evening I walked in the dark across the waste land opposite to the hotel where I had seen the rats. They were not visible, but I was mindful of their presence. From time to time I also had to step round heaps of old rags on the pavement, and it was a while before I realised that they were people.

I had arranged with Mr.Manu to meet him with the car at the airport the next day, before my flight home. His first words were “Are there any scratches?”. By some absolute miracle there were no more than when I collected it, and I am surprised that after seven days driving in India it had not been reduced to a heap of scrap metal. Anyway, he was quite happy with it, and handed over my £720 deposit. Kerala Self-Drive Car Rentals are good people, and I would recommend them to anyone else who is foolish enough to consider driving in India.

Other people who go to India come back with wonderful stories of the Taj Mahal, fantastic scenery and wildlife. All I seemed to do was face death twenty times a day and struggle against the intense heat. I wonder which of these scenarios is closer to reality.

Japan 2015

CLICK ON PICTURES TO ENLARGE

JAPAN 2015

This was to be essentially a holiday combined with a brief visit to a Japanese company with which I have had a business relationship for many years. It would be my second trip to the country, with a similar itinerary to the one I had made eight years previously, travelling around by self-drive hire car. When I originally suggested that idea the advice I was given by people who knew anything about Japan ranged from 'inadvisable' to 'impossible', but in the event it was very successful. Starting from Osaka the route covered about 1000 miles, taking in coastal areas, mountains, beautiful countryside and several major cities. Car museums as well, of course.

Despite my experience, in planning this new 11-day trip I made a major blunder. After booking the flights with Emirates I discovered that it was difficult to make any hotel reservations for the first five days that I was going to be in Japan because the three week days were public holidays. The Monday was Respect for the Elderly Day, which I rather liked, the Wednesday was Equinox Day, and Tuesday was a holiday because the other two were. The Japanese are inveterate travellers, and when they decide to move around they do so in a big way, putting a lot of pressure on accommodation and transport. There were still 8 weeks to go, and with great difficulty I managed to book hotels for the whole route, mainly using Booking.com, but it reduced my flexibility and would create big problems if I lost a day anywhere. Also I had to alter my business visit, and the roads were likely to be even more congested than usual.

Hello, Japan. Dancing chairs and bottled sweat.

About 25 hours after leaving home I went into the station at Kansai Airport to get the Haruka Limited Express train to Shin-Osaka, and was immediately left in no doubt that I was in Japan. The train pulled in exactly on time, and I was just entering the carriage to take my numbered seat when a man stopped me and told me to wait behind a line on the platform. He wheeled a trolley full of cleaning stuff into the carriage, and then something happened straight out of Alice in Wonderland. All the seats, which were in lines of 2 or 3, started spinning round on their bases individually. It was just like some sort of crazy Mad Hatter's dance, and appeared to be part of the cleaning procedure, but was actually a way of turning the seats round to face the direction of travel for the return journey as the train was at the end of the line.

It was too dark to see anything much outside, so I took the opportunity to check my navigation arrangements. Finding the way in Japan can be very difficult and locating specific addresses is a big problem even for the locals because in most places buildings are not numbered in sequence along a road or street, but are identified by three numbers referring to the district, block and the number within the block. This last number may be determined by the order in which the buildings were erected, which is not very obvious to a foreigner. If a street has a name it will almost always only be in Japanese unless it is a major route.

To find a particular building you really have to know exactly where it is on a map, and there is something rather peculiar about the Japanese and maps. The maps you find in leaflets and public places are strangely presented and usually do not have north at the top. If you buy a local map it will be entirely in Japanese. Of course, you can always ask somebody, but almost nobody speaks English, which means that they will go off in search of someone who does. As a point of honour they will not let you go until they are satisfied that they have met your needs, which can take a very long time. Businesses often have outline maps on which they will mark the place you are looking for, but they usually get it wrong. It is no good showing someone an address in English because they won't be able to read it, and if you have the address in Japanese you won't be able to read it!

Rental cars usually come with satnav, but it will be all Japanese apart from the road numbers. This means that you need GPS in a phone or tablet, and there is still a problem, because for some strange reason to do with copyright the usual map providers (Google, Bing, HERE) do not have offline maps of Japan. However, after much research I found a modified version of Bing Maps for my Windows phone, and MapsMe for my Android tablet.

Back to the train, and this was the opportunity to see whether the GPS worked with the maps, because I couldn't do it England. To my great relief the little arrows moved along the maps and showed the position of the train, so that I could judge exactly when it was going to get to Shin-Osaka station, although there were clear indicators in the carriages anyway. I chose Shin-Osaka as my base because I knew the area from my previous visit. It has lots of hotels, was convenient for car rental and not too far from my business associates’ headquarters.

Shin-Osaka might have lots of hotels, but I had only been able to find one with a vacancy for the day of my arrival, and in my estimation it was at least twice the price that it should have been. It was very close to the station in a road alongside the railway lines, and I must admit that I did wonder whether it offered services over and above those required for a normal night’s sleep, but there was nothing untoward in the reviews. The name LiveMax also seemed a bit strange, but in fact it is part of a large Japanese hotel and real estate group, and was perfectly respectable.

In the last thirty hours I had had a succession of airline meals, so I was still a bit hungry, and after checking in I went along the street to get something from a convenience store. On the way I passed several of the refrigerated drinks dispensing machines found everywhere in Japanese towns, and containing among many other things bottles of Pocari Sweat and Calpis energy drinks, always a source of amusement to native English speakers. They taste as bad as their names suggest, although Pocari is not actually bottled sweat, but just intended for sweat replacement.

These are just two examples of the very widespread use of English names for products and businesses, which seems very odd in a country in which so few people speak the language. Most hotels have English names, and the two most popular convenience stores are Lawson and Family Mart. Almost every door for public use in Japan has PUSH and PULL on it, a point that I raised with my business associates in a general discussion until I realized that it was dangerous ground and changed the subject.

Mountains and mad motorcyclists.

The next morning I checked out and went to pick up my car from Times Car Rental, a short walk from the hotel. Shin-Osaka, like most urban areas in Japan, is totally safe but visually unattractive, a consequence of the headlong rush for development in the 1960s and 70s. The main street, if you could call it that, is literally overshadowed by a multi-lane elevated highway running for its entire length (and far beyond), with two high level railway stations.

The staff in the car rental office did not speak much English, but after examining my credit card and International Driving Permit they handed me some forms in English to read and sign where indicated. A man took me outside to introduce me to my silver Mazda Demio (Mazda 2 in England) and then left me to get sorted out. Driving in Japan is on the left hand side of the road, with the steering wheel on the right, as at home, but there was one confusing thing, in that Japanese cars in Japan have the lever for the indicators on the right and one for the windscreen wipers on the left. It took me several days to get used to that, and for a time I kept switching the wipers on when I wanted to turn.

Seventy-two percent of the area of Japan is mountainous, which means that a large proportion of the remaining land is built up, with vast, seemingly endless, conurbations along the coasts. My next overnight stay was to be in a small town called Obama on a relatively undeveloped stretch of coast about 50 miles north of Shin-Osaka. It was the other side of a range of mountains, and there were basically three ways of getting there, one being made up of comparatively minor roads across the mountains, and the other two being expressways (expensive toll motorways) on lower lying land to the east or west of the mountains. These last two were each about 100 miles long, and the more direct route was actually about 90 miles, because it squiggled about so much.

There was an element of risk in the last route, as Japanese mountain roads are subject to closures during periods of bad weather, including heavy rain, of which there had been plenty prior to my visit. On the other hand at holiday time there could be problems on the expressways, as on British motorways, and my inclination was to take the mountain route. The traffic north of Osaka on the Sunday morning was horrific and I spent about two hours going nowhere, mainly because of people queuing to get into shopping malls. However, once I got out of that area the traffic cleared and I made quite good progress.

The road ran mainly between tree-covered hills, with villages and a couple of small towns along the way. For some distance it was close to an expressway on which signs at the intersections warned of queueing traffic, so I think I made the right decision to avoid using the supposed high-speed route. For the last forty miles to Obama there were few other vehicles apart from lunatic motorcyclists flying round the endless hairpin bends with their knees scraping the road. The scenery was not as spectacular as might be expected from the map, because of several tunnels through the highest mountains, including one about a mile long.

Obama festival chaos

At 4.30 I arrived in Obama, to find the streets leading to my hotel closed off by people with batons standing in the road. In Japan there are lots of people with batons controlling the traffic, some obviously police, but others employed by businesses or for special events. Nowadays they have batons with lights in them like the light sabres in Star Wars, but shorter and the lights are red. In the distance I could see people marching in traditional costume and there was obviously a festival of some sort in progress.

Eventually I managed to get to the hotel, which was at the centre of the action, and once sorted I went for a walk around. It seemed that there were several groups marching about, two or three of them with marvelous tall medieval carriages packed with people, pulled by strong men with ropes. The carriages were made of wood, including the wheels, and were draped with elaborately-patterned cloths.

The main street was lined with stalls selling the usual tourist fare and all sorts of unrecognizable items of food, none of which appealed to me. At one end of the street was a large shrine, with a kind of altar in front of it and brightly coloured ropes hanging down with enormous tassles. People would come and bow for a while before shaking the tassles, causing bells to ring, presumably as a form of prayer. After a good and cheap rice meal in a restaurant I walked around the town and through to the promenade which overlooked a bay on the Sea of Japan. Obama was an attractive place and I felt pleased with my choice of night stop.

Breakfast in the hotel the next morning was not available to me because I had not booked it in advance. The streets of the town, with colonnades, were deserted, and the shops mostly closed but I resorted to breakfast in a convenience store before exploring the town a bit more. Eventually I found a fair part of the population in a food and fish market near the harbour, where a vast variety of freshly-caught fish were beautifully displayed on slabs.

Heavenly views, tunnels and eating with the locals

The plan for day was to follow the coast northwards for about 80 miles and then turn inland to a city called Fukui. Soon after leaving Obama I followed

a sign to the Angel Scenic Drive which led me on to a cul-de-sac mountain road to the top of Mount Kusuyagadake, on a peninsular. It lived very well up to its name with superb views across the bay and ocean on both sides. At the top was a massive car park with about three cars in it, although the inevitable group of motorcyclists turned up after a few minutes. A very nice well-travelled couple from Kobe came over and talked to me for a while. They were astonished that I was driving around on my own, because few Japanese people have ever driven in a foreign country and they find it hard to imagine doing it.

By now I was completely used to the ridiculously low speed limits on Japanese roads. For almost the entire distance since I left Shin-Osaka the speed limit had been 40kph (25mph) or 50kph (31mph), even on open country roads. These limits are normally exceeded by a margin of about 50%, i.e. people do 60kph in the 40 limit and 75kph in the 50 limit. Motorcycles go as fast as they can. Police cars are few and far between as are cameras, and little effort is put into enforcement.

The main road wended its way along the coast past tiny fishing ports, from time to time passing through tunnels where the mountains came down to the sea. I counted nine tunnels in about thirty miles to the town of Tsuruga. Continuing to follow the coast line I stopped for a walk in a couple of small places right alongside the ocean and was surprised to find that there was lots of free parking and not many people about. It is always said that you cannot find anywhere to park in Japanese towns and cities, which is not actually true. It is usually easy to find somewhere, but just very expensive, although no more so now than in cities like London, Brighton or Oxford. In some places the main road (Rt.305) was uncomfortably narrow, which might explain the lack of buses, and therefore people.

Eventually I turned inland to Fukui, an industrial city which has a population of 267,000, and managed to find the Route-Inn Court Hotel, in the middle of a big commercial development. For my main meal of the day I went into a nearby restaurant, sat down and waited to be served, without realizing that it used a system that is widespread in the sort of cheap Japanese places that I frequent but had forgotten about. A member of staff came over and indicated that I should follow him into the lobby, where there was a big cabinet with dozens of tiny pictures of meals. Below each picture was a brief description of the meal in Japanese, the price, a button, and a small slot. The procedure is to decide on a meal that does not look too revolting or poisonous, put an appropriate amount of money into a big slot on one side, and press the relevant button. A little ticket then pops out through the small slot for you to give to someone in the restaurant and after a few minutes the meal will be put in front of you. At that point it is no good saying “Oh no, I pressed the wrong button”. You just have to knuckle down and get on with it, chopsticks and all.

Old cars, old houses and scenery

For most people the highlight of a trip to Japan would be a visit to a historical monument or cultural event of some sort.

For me it was the Motorcar Museum of Japan at Komatsu, a name that will be familiar to anyone in the building industry as it is the home of one of the world’s largest construction machinery manufacturers. The museum is an extraordinary place with an extraordinary history.

An extremely imposing European-style red brick building, it was put up by the man who introduced such bricks to Japan during the massive building boom of the 1960s and ‘70s. He had a fleet of lorries that delivered the bricks to sites all over the country, and one of his customers asked him to take some old cars away on the empty lorries after the delivery. He offered this service to other customers, and eventually finished up with 500 cars in a field, leading to the establishment of the museum . In front of the building stand two classic British red telephone boxes and a matching red postbox, with a notice in Japanese that presumably states “Do Not Post Letters in This Box”. Apart from the display of cars there is another rather unusual collection ‘Urinals From Around the World’, twenty seven in total, all in working order and labelled with their country of origin. Even I couldn’t test all of them during my visit.

At mid-day I left the museum with a long cross-country drive in front of me, to the ancient town of Takayama, which is remotely situated in a mountainous area of Central Honshu. From Komatsu it is possible to cover a large part of the journey on expressways, including an eight-mile long tunnel, but I preferred to use the old roads because it would be more interesting and I am too mean to pay the tolls.

Before leaving Komatsu I stopped to fill up with petrol, which was an unforgettable example of the application of Japanese culture to what would normally be a mundane experience. Like most filling stations, this one had attended service, with two young men who smiled and bowed as they waved me into position by one of the pumps. With a slight hint of anxiety one of them looked at me and said “Casha?” when he realized that I was a Westerner, because he was worried that I would offer him a credit card that he could not accept, which would be very embarrassing. I assured him that it was “casha” and he put the petrol in while the other man ran round the car washing all the windows. No tip was expected for this service, and my departure was accompanied by a session of bowing and waving to an almost absurd extent.

Once clear of the coastal town of Kanazawa it was back into the mountains, with miles of hairpin bends and a few tunnels, until I suddenly found myself looking down on a group of ancient thatched houses. This was the Historic Village of Gokayama, a world heritage site and major tourist attraction. It was not short of visitors, but I was guided into a parking space and set off to look round.

The houses were built of wood with steeply pitched thatched roofs in a chalet style, usually with one or two upper stories and were well spaced out between roads and small rice fields. The village was essentially traffic-free, although a few cars were tucked in here and there. Alongside a river and surrounded by wooded hills, it was an idyllic setting but gave the impression of being somewhat over-preserved.

About 15 miles further along the road was another larger and possibly more authentic place called Ogimachi, where I had stayed on my previous trip. Still with wooden buildings, many thatched, the main street is normally open to traffic, and it has a few shops, traditional guest houses and a petrol station. When I arrived the street was closed, with traffic being instructed to take the clogged-up bypass which runs through a tunnel. Vehicles were queueing to get into the other end of the village, apparently for an evening event of some sort, so I had to give it a miss, an unfortunate consequence of the holiday period.

It was still about fifty miles to Takayama through tunnels, past lakes and mountains which meant that it was dark some time before I reached the town. One thing I do not like about Japan is that they will not have daylight-saving time, so in late September it was dark soon after 6pm, very much earlier than at home. I had resolved to avoid driving in the dark, because the road markings and street lighting are poor compared with England, but fortunately the road into the town led straight to the station, which was opposite to the inappropriately-named Country Hotel where I was staying. Even in Japan everybody knows the way to the station.

Takayama is famed for its Old Town with traditional single-storey wooden buildings lining the streets, and the plan for the next day was to have a look round before driving over yet more mountains to Matsumoto. In a street not far from the hotel was the Hida Kokubunji Temple with its three-level pagoda. It seems strange to find a building like that in the middle of a densely built-up area, but it is really only the same as coming across a church or chapel in an English town.

Alongside a river running through the old town I found a morning market, extremely well attended not only by Japanese people, but also Westerners who were presumably on organized tours. It was a few days since I had seen a Westerner, and as I have found before, it came as quite a surprise. After spending only quite a short time among people of oriental appearance I felt as if I was one of them and the Westerners struck me as being different!

The old town appears to be quite authentic, with people living and working in the wooden buildings as they always did, although nowadays geared largely to tourism. Many of them are traditional Japanese guest houses in which ancient customs are upheld, such as sleeping on the floor and communal bathing. Had it not been for the pressures of the holiday period I am sure I could have stayed in one, as I did in Ogimachi on my previous trip, but I doubt whether I could have got in this time without pre-booking, which was virtually impossible from England.

More tunnels, a mountain pass, and a castle challenge

It was the last day of the five day holiday period, and I expected that people would be setting off home to the heavily-populated area in the south. My destination for the day

was Matsumoto, about 70 miles to the east, the other side of some sizeable mountains, and as predicted the road (route 158) was busy but the traffic kept moving quite smartly for about 30 miles. Some distance after a long tunnel it came to a right turn with a toll booth into another tunnel, and all the traffic in front and behind went that way, leaving me driving straight ahead on my own. The road dwindled down into something like a country lane and started climbing, ultimately turning into the Abo Toge pass, one of the best drives I have ever done. When I got to the top it was some time before another car appeared and I began to wonder if the road was actually closed. The descent had a succession of tight hairpin bends that were beautifully depicted on the car satnav, about the only time it had shown anything useful, and eventually the road rejoined route 158 to go through at least another 12 tunnels before reaching the outskirts of Matsumoto.

An essential part of any trip to Japan is a visit to a castle. The ultimate Japanese castle is usually considered to be Himeji, which I had been to previously, but was not on my present itinerary. The best opportunity this time was Matsumoto and as I entered the town I decided to go straight to the castle and to the hotel afterwards, because of the time. Although it is not as 'good' as Himeji, its appearance fulfils most people's expectation of a Japanese castle in every respect.

An essential part of any trip to Japan is a visit to a castle. The ultimate Japanese castle is usually considered to be Himeji, which I had been to previously, but was not on my present itinerary. The best opportunity this time was Matsumoto and as I entered the town I decided to go straight to the castle and to the hotel afterwards, because of the time. Although it is not as 'good' as Himeji, its appearance fulfils most people's expectation of a Japanese castle in every respect.

Just inside the entrance was a notice stating that the waiting time for entry was 20 minutes, and beyond that was a covered area with about 200 people sitting on wooden benches. This was obviously the holiday factor in action, but we were actually taken in in batches of about 100 at a time at 10 minute intervals, so the proverbial Japanese punctuality was upheld. As soon as we got through the door we were required to remove our shoes and given a plastic bag to carry them in. At Himeji visitors were provided with slippers which were a source of some amusement because none of the Western men could get into them. The largest were about English size 7, and I take 9 (EUR 43), so I was left with my socks. At Matsumoto no slippers were provided, so it was socks or bare feet anyway. This might not have seemed too bad, had the floors and particularly the stairways not been so highly polished.

Progress was painfully slow, as the vast crowd was forced onto a single line that snaked its way up five flights of steep slippery stairs to the top of the building and down again. According to a notice the steepest flight was at an angle of 61 degrees from horizontal with a rise of 41cm between the treads. In Britain I am sure this would have been banned by the Health and Safety Executive, and I was astonished by the way the Japanese people, many of them elderly, tackled it with great determination. Going down was more difficult than going up, and surely they can't all have been in the navy?

Various historical items, mainly weapons, were on display as we went round, but the most memorable parts of the tour were the views from the upper floors, which were superb. From the castle it was only a short distance to the centre of the city, which comes across as quite European in character. The one major difference from most Japanese city centres is the absence of the incredibly ugly overhead cables that ruin almost every photograph that you try to take anywhere else.

It was time to find the Route-Inn Court Hotel, and I was pleased to discover that it was actually shown on the map in my phone. In the reception I gave the booking form to the young lady, who took it into the office, emerging shortly afterwards to explain with some difficulty that I was in the wrong hotel. I pointed out that the hotel pictured on the booking form was the one we were in, and she agreed in a vague sort of way, but still insisted that it was the wrong one. She started to draw a sketch, explaining that the hotel I wanted was another Route-Inn Court just off route 19 about three kilometers away. By now it was dark and I realized that I was going to have a monumental task in finding this other hotel from the information she had given, when I suddenly thought that if one Route-Inn Court was shown on my phone the other one probably would be. It was, and when I got there it turned out to be a building absolutely identical to the first one, so it seems that Route-Inn buy their hotels from a catalogue.

The hotels I had stayed in so far were ‘business’ hotels’, which, as the term suggests, cater for the vast number of Japanese business travellers, but are not very well set up for foreigners, often having no one who can speak more than a few words of English. The breakfasts, where they were provided, offered a fair selection of items, some hard to identify and labelled only in Japanese, so it was a bit hit and miss for me but I managed to find enough to fend off starvation. As a last resort there were always the Lawson and Family Mart stores, which had coffee and Western style food at cheap prices.

A feature found in most en-suite rooms in Japanese hotels is the high tech lavatory. When I first heard about such things some years ago I thought it was a joke, but they are deadly serious about it. Alongside the seat is an arm with a selection of controls to enable the toilet to perform a range of washing and flushing actions, including a bidet function and sometimes music to drown out any unwanted sounds. The lengthy instructions are provided in Japanese and in some cases also English, the more upmarket versions having a detachable panel to facilitate remote operation from anywhere in the room, although it is hard to see why anyone would want to do that.

some years ago I thought it was a joke, but they are deadly serious about it. Alongside the seat is an arm with a selection of controls to enable the toilet to perform a range of washing and flushing actions, including a bidet function and sometimes music to drown out any unwanted sounds. The lengthy instructions are provided in Japanese and in some cases also English, the more upmarket versions having a detachable panel to facilitate remote operation from anywhere in the room, although it is hard to see why anyone would want to do that.

A weird museum, bad weather and a Fuji non-event