Cyprus 2019

CLICK ON PICTURES TO ENLARGE

CYPRUS 2019

Why Cyprus? Well, I was looking for somewhere to go in November that would be warm, not too far, be politically interesting and, of course, have some classic cars. In general I have never been very attracted by the Mediterranean, but this time Cyprus seemed to fill the bill.

Why Cyprus? Well, I was looking for somewhere to go in November that would be warm, not too far, be politically interesting and, of course, have some classic cars. In general I have never been very attracted by the Mediterranean, but this time Cyprus seemed to fill the bill.

Situated between Turkey and Greece, the population has long been made up mainly of people from those countries and for many decades up to 1878 the island was part of the Ottoman empire. In 1878 Turkey and Britain signed an agreement whereby Turkey would retain sovereignty but ceded the administration to Britain, who wanted a military presence in the area. In due course Britain took complete control until the 1950s, when the British came under attack from EOKA, a Greek nationalist group. This was followed by serious friction between the Greek and Turkish communities and in 1960 the independent Republic of Cyprus was created, with Britain retaining a few small areas for military purposes.

Political instability continued and in 1964 the UN sent a peacekeeping force led by a British general who drew a line with a green pen marking the division between the Greek and Turkish occupied areas of Nicosia which eventually spread across the whole country and became known as the ‘Green Line’.

The unrest continued with some American involvement until in 1974 Turkish forces invaded from the north and the Greek and Turkish populations became ever more divided. The UN has been in the area ever since, and a political settlement still seems to be a long way away. The Greek occupied area south of the Green Line is internationally recognised as the Republic of Cyprus, is a member of the EU and uses the euro as its currency. The Turkish area north of the line calls itself the Turkish Republic of North Cyprus and is only recognised as an independent state by Turkey. Its currency is the Turkish Lira. .Since 2003 it has been possible to go through the green line in both directions and many people do.

This is a very sketchy description of a complicated situation and more detailed accounts can be found in the Lonely Planet Guide to Cyprus and the Bradt Guide to North Cyprus.

I remember the partition of Cyprus very well. In England at the time I had a girl friend named Dinah whose parents had died and left her a house. She had enjoyed several holidays in Cyprus, and sold the house in England with a view to buying one in Cyprus. She asked my advice and I told her it was risky, but she never took my advice anyway. Her pen was practically paused in mid-air over the contract when the Turks invaded, and in a rare flash of common sense she changed her mind and decided not to sign away her inheritance.

Language

As might be expected, Greek is the main language south of the Green Line, and Turkish is generally used in the north, while English is widely spoken everywhere, although I did have some difficulty in the north (see later). When translated into Latin (English) characters many places have 2 or 3 names. For example the capital is known as Nicosia in English, Lefcosia in Greek and Lefcoșa in Turkish. If you drive over the mountains from Paphos to Nicosia most if not all of the road signs only refer to it as Lefcosia, so it is important to know these differences. Place names on road signs and maps will also be in Greek characters in the south and have some Turkish characters in the north, so the situation is quite complicated. It can be difficult to put place names into a British satnav.

Larnaca (Larnaka, ΛΑΡΝΑΚΑ)

There are direct flights with easyJet taking about five hours from Gatwick to Larnaca, on the south east coast of Cyprus. Everything went well and the Fiat Tipo was ready for me at Budget Car Rental. I had booked for two nights at the Elysso Hotel, which is on the north side of the town about five miles from the airport and the satnav led me in the dark straight to the hotel, which was in its database. This was fortunate, because none of the surrounding street names were. A relic of the British occupation is that traffic drives on the left.

The hotel did not have a restaurant other than for breakfast, but recommended one round the corner. The meal, although it was too big for me and not greatly to my taste, provided me with the necessary sustenance as I had not eaten since mid-day.

My second-floor room was overlooking an urban duel carriageway with traffic lights in one direction and a roundabout in the other, with a 50kph (31mph) speed limit. For two or three hours it seemed to serve as a sprint course for fast cars and motorcycles, some of which must have been doing 90mph (I am not joking) as they went past my room. The noise was tremendous and the police must be aware of what goes on, but I think they just let the boys have their fun for a couple of hours in the evening when there was not much traffic.

Although the hotel had an underground car park they suggested that it would be easier if I left the car on an area of waste ground opposite which already had several vehicles on it. They assured me that it would be safe and that proved to be the case. In fact, I came to realise that, as the guide books said, Cyprus is in most respects a very safe country. The highest risk is probably in driving, and although worse than Britain it is far better than in many countries I have been to.

The overall plan now was to have an easy day in Larnaca and then spend six days on a more or less circular route, driving along the coast to Paphos, over the mountains to Nicosia and back to Larnaca..

The next morning I drove most of the way along the sea front, parked near the Fishing Shelter and walked down to Mackenzie Beach at the far end of the built-up area. The weather was just perfect, clear blue sky, warm but not too hot. There were few people around and next to the road was a cycle track on which youths were tearing along on electric scooters and fat wheeled bicycles of the type that are not allowed in public places in England. I immediately decided that I wanted one, and asked the youths where I could hire one. They directed to me a place that I would pass as I walked into the town and when I found it the man in charge said there were no bikes available until 2pm because the youths had run the batteries down!

The next morning I drove most of the way along the sea front, parked near the Fishing Shelter and walked down to Mackenzie Beach at the far end of the built-up area. The weather was just perfect, clear blue sky, warm but not too hot. There were few people around and next to the road was a cycle track on which youths were tearing along on electric scooters and fat wheeled bicycles of the type that are not allowed in public places in England. I immediately decided that I wanted one, and asked the youths where I could hire one. They directed to me a place that I would pass as I walked into the town and when I found it the man in charge said there were no bikes available until 2pm because the youths had run the batteries down!

On the way into town I passed a small general store with a window full of English magazines and newspapers, so there must be a considerable British presence in the area. At 11.00am the newspapers had that day’s date, so they must be printed in that part of the world, something that is easily done with modern technology. The prices were about double those in England which made the Daily Telegraph £4, so I decided that I could make do with my tablet and the hotel wifi later on.

After some distance I came to the castle and the start of the main beach area. The town centre was set back some way from the beach and had a number of attractive stone buildings, including the dominant St. Lazarus Church and a mosque. This was basically the old town with a selection of small shops, the big stores and supermarkets being further out as is usual nowadays. Facing the next stretch of beach with palm trees was a long line of restaurants and takeaways including McDonald’s, Burger King and many more upmarket establishments. A wide strip of the beach was effectively private and covered with loungers and sunshades, but there was a public area between that the sea.

At the north end of the beach was a wooden fishing pier and marina. Beyond that is the commercial harbour and there is no further access to the beach for a considerable distance.

At the north end of the beach was a wooden fishing pier and marina. Beyond that is the commercial harbour and there is no further access to the beach for a considerable distance.

The town was not at all crowded and a high proportion of the people around were British. The weather was really beautiful, and I could understand why people retire to a place like that, although I think I would get bored fairly quickly. No doubt there is a thriving British community and I am sure it is great if you like playing card games. Of course, the weather is not always perfect, and from November onwards there is a lot of rain at times.

After a wander round the town I made my way back to the car. It was later than I expected, so I decided to leave the electric bike until the next week when I would have some more time in Larnaca.

Limassol (Lemesos, ΛΕΜΕΣΟΣ)

The next morning I followed the coast road to the airport, stopping to look at the Salt Lake, with its large population of birds. There are supposed to be flamingos, but I didn’t see any. It was my intention to take the coast road to Limassol but after messing around at the back of the airport I could not find it and took the motorway instead.

The main purpose of going to Limassol was to visit the Cyprus Historic and Classic Motor Museum, which was easily reached without going into the town. The museum is privately owned and contains about 150 vehicles, from the obligatory 1886 Benz replica through to 2004 and includes cars used by famous people such as President Makarios lll, Mrs.Thatcher and Mr.Bean. For the enthusiast it is a good varied collection and worth visiting.

Close to Limassol is the British Sovereign Base at Akrotiri which was frequently mentioned on the radio in the days of ‘Family Favourites’ and similar programmes for British forces overseas.

After leaving the museum I found myself in Episkopi, another name from the past which is like a little bit of England with housing estates and other facilities for the forces.

Paphos (Pafos, ΠΑΦΟΣ)

The motorway from there to Paphos was quite mountainous in places, with good scenery. I did not have a hotel reserved in Paphos and started looking for one when I arrived at 4.00pm. In November I thought it would be easy to find accommodation, but the first hotel I tried was full and the second was closed for the winter. I drove right through the town to the beach area and very quickly found the Pandream Hotel Apartments about 100 yards from the beach for £37 a night. It was quite a large Spanish-style place with only a handful of guests and I had a big second floor room with a sea view from the balcony.

The Tea for Two restaurant was separate on land adjacent to the beach, and as I walked down it inthe morning I saw a very smart 1950s Vauxhall go past. When I turned the corner I was surprised to see that the restaurant car park was full of classic cars, and it transpired that it was the monthly breakfast meeting of the Paphos Classic Vehicle Club. There were at least 30 people, mostly retired couples, and there is obviously a large ex-pat community in the area. After breakfast I set off along the beach and almost everyone around was British.

In the summer Paphos is a popular resort and am told that it is very hectic, but in November, even with the beautiful weather, it was not at all crowded.

A path called the Coastal Broadwalk runs along the sea front past the town centre, the marina and the archaeological site entrance, right to the castle at the end, a distance of about two miles from my apartment. In the marina was a strange vessel, obviously based on Jules Verne’s Nauilus submarine. Upon further investigation it proved to be an eight-seater 7D cinema, but unfortunately was closed. How the 7D works I cannot imagine.

A path called the Coastal Broadwalk runs along the sea front past the town centre, the marina and the archaeological site entrance, right to the castle at the end, a distance of about two miles from my apartment. In the marina was a strange vessel, obviously based on Jules Verne’s Nauilus submarine. Upon further investigation it proved to be an eight-seater 7D cinema, but unfortunately was closed. How the 7D works I cannot imagine.

Nearby was the entrance to the archaeological site, which caused me to have a rare and brief attack of culture. It covers a considerable area of ground and is still being explored.

It dates from the 4th century BC and houses the famous Pafos mosaics, which I had actually never heard of. The mosaics tell the stories based on ancient Greek myths, which are explained in Greek and English on information boards. Some of them are inside buildings and some out in the open. One thing I liked was that they had incorporated some odd small areas of mosaic into the concrete paths so that you could actually walk on them.

The day seemed to pass very quickly and finished with a meal at the Tea for Two restaurant.

Over the Troödos Massif to Nicosia

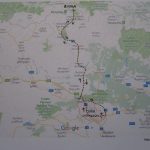

The next morning I set off to drive over the mountains to Nicosia. At 1952m (6404ft) the highest mountain in Cyprus is Mount Olympus, which is roughly half way between Paphos and Nicosia, and stands in the middle of a range called the Troödos Massif.

The roads in the area are very complicated, and looking at the map I decided to aim for a place called Pano Platres, which was recognised by my satnav. The route retraced my steps on the motorway towards Limassol for some distance before turning off onto the mountains. Then followed about 25 miles of beautiful scenery with a long climb up to Pano Platres, after which I got hopelessly lost, despite all my GPS equipment. I still don’t understand how it happened, but there were a vast number of small roads with tourist signs and nothing that I could recognise on the map or put into the satnav.

It was considerably cooler than on the coast, and there were signs to ski resorts, although it was nothing like cold enough for that. Eventually I got on to the main road B8 which goes close to the summit of Mount Olympus before dropping downhill (as the B9) in the direction of Nicosia. From Paphos to Nicosia is 148km (92miles) via the motorway, but my mountain route took far longer than that, and I finally got to the outskirts of Nicosia at about 3pm.

Nicosia (Greek side: Lefcosia, ΛΕΥΚΟΣΙΑ. Turkish side: Lefkoșa)

The hotel that I had booked was right in the old city, in the centre, and I did not realise how difficult it would be to get there on a Sunday afternoon. The narrow streets were packed with people and it was sheer driving hell getting to the hotel, reminiscent of Istanbul and towns in India. The hotel was supposed to have a car park, but when I got to it I could not even stop, let alone park, so I struggled on until I found a public car park some distance away. While I was looking at the map trying to work out how to walk back to the hotel a very refined-looking young lady came up to me speaking excellent English and offered to help. She suggested that we ask the car park attendant, and as we walked over she asked where I was from. I told her “England” and asked where she was from. She said “Moscow”. Moscow!! It was about the last place I expected. When I was in Moscow most people I met were pleasant enough but didn’t look very refined or speak English.

Anyway, I managed to find the way back to the hotel on foot, and the staff showed me how to get to their car park, which meant reliving the nightmare of driving in the tiny back streets. Once sorted I went for a walk along Ledra Street, which is the main artery of Greek Nicosia and leads to the checkpoint on the Green Line for pedestrians into Turkish North Nicosia. It was my plan to go through into the north the next day.

When I was planning the trip there were two places north of the Green Line in Nicosia that I particularly wanted to go to, namely the Turkish area of the city and a car museum in the Near East University about five miles north of the centre.

I could not take my car into the north, which meant I would have to get to the university either by taxi or bus. From experience I don’t like taking taxis in foreign cities, so the best option would probably be the bus.

On the Monday morning the area round the hotel was very quiet and the car parks were almost empty, a complete contrast to the previous afternoon. On the Greek side Ledra Street is quite modern with smart shops and restaurants, many with familiar names. At the checkpoint I had to show my passport both sides. There was no queue. On the north side everything changed, with old narrow streets and a vast bazaar-like market, some of it under cover. Walking more or less directly northwards on Girne Caddesi took me through a square with shops and banks to Kyrenia Gate, where there was an old building containing a tourist information centre. The man in the office gave me a map of north Nicosia and told me where to get the bus to the university.

Kyrenia Gate is a gate in the city wall, known as the Venetian Wall, which surrounds the whole of the old town and is remarkably intact. It dates from 1567 and has 11 fortifying bastions equally spaced around it giving it a shape something like a snowflake on a map. The wall was intended to keep out Otterman invaders, but failed miserably in 1570 when the Ottomans broke through and killed 50,000 of the city’s inhabitants. Around the outside of the wall is a wide strip of land like a dry moat.

Kyrenia Gate is a gate in the city wall, known as the Venetian Wall, which surrounds the whole of the old town and is remarkably intact. It dates from 1567 and has 11 fortifying bastions equally spaced around it giving it a shape something like a snowflake on a map. The wall was intended to keep out Otterman invaders, but failed miserably in 1570 when the Ottomans broke through and killed 50,000 of the city’s inhabitants. Around the outside of the wall is a wide strip of land like a dry moat.

The Gate is at a junction with a very wide road almost like a ring road where all the buses stop, but the set-up was a bit vague. There were some people who looked like students, and I asked them where the bus stop for the university was, and they said “Here, just wait and the bus will come”. I suddenly realised that I had no Turkish money and asked the students if I could pay with euros on the bus. They said if I was going to the university it was free.

Different buses kept coming, most of them quite small with destination boards in the front windows. Suddenly a big red bendy bus came and the students all surged forwards, so I assumed that this must be the one. It was standing room only, and was very uncomfortable, with a lot of jerking and jolting. As I was between 50 and 60 years older than everyone else on the bus I have to admit that when a student offered me his seat I accepted it. I suddenly noticed a sign on the door extolling the advantages of the Oyster card, and another one behind the driver saying that there was a £50 fine for travelling without a ticket, giving an Arriva phone number. The truth dawned – this was one of Ken Livingstone’s congestion-causing cyclist-killing ex-London Transport bendy buses, spending its retirement carrying students in Cyprus.

The Near East University (NEU)

The expression Near East is not used in Britain, but is used in some other European countries to describe what we call the Middle East. The Near East University in Nicosia is an extraordinary place. It was founded in 1988 by a Turkish Cypriot named Suat Günsel, who still owns it. It has over 25,000 students, including many from the Middle East and Africa, plus 1200 academic staff. There are 16 faculties, 4 graduate schools and 15 research centres. Also primary and secondary schools and a kindergarten. The campus covers 98 hectares with a Congress Hall, a huge library, a supercomputer, a hospital, a mosque, a Communications Museum, an Art Museum, and most importantly the Museum of Classical and Sports Cars.

describe what we call the Middle East. The Near East University in Nicosia is an extraordinary place. It was founded in 1988 by a Turkish Cypriot named Suat Günsel, who still owns it. It has over 25,000 students, including many from the Middle East and Africa, plus 1200 academic staff. There are 16 faculties, 4 graduate schools and 15 research centres. Also primary and secondary schools and a kindergarten. The campus covers 98 hectares with a Congress Hall, a huge library, a supercomputer, a hospital, a mosque, a Communications Museum, an Art Museum, and most importantly the Museum of Classical and Sports Cars.

This last item was, of course, the purpose of my visit. For a change I had done my homework and knew whereabouts in the vast campus the museum was situated. From the map in my phone I could follow the movement of the bus as it crawled along the complicated road network, and got off at a point reasonably close to my target.

At 20 euros the entry fee to the car museum was a bit over the top, but I had come a long way and I could hardly change my mind about going in. There were 140 cars displayed in two sections, classic cars and modern high-performance sports cars. A considerable number of the classic cars were British, including a Rolls-Royce Silver Shadow, a Jowett Javelin and Riley RM. The sports cars included Ferraris, Mercedes, and other exotica from around the world. I suppose having a display of cars worth millions of pounds in their midst gives the students something to aspire to, but it does seem rather odd in some ways.

At 20 euros the entry fee to the car museum was a bit over the top, but I had come a long way and I could hardly change my mind about going in. There were 140 cars displayed in two sections, classic cars and modern high-performance sports cars. A considerable number of the classic cars were British, including a Rolls-Royce Silver Shadow, a Jowett Javelin and Riley RM. The sports cars included Ferraris, Mercedes, and other exotica from around the world. I suppose having a display of cars worth millions of pounds in their midst gives the students something to aspire to, but it does seem rather odd in some ways.

The next challenge was to find the bus back to the city. It was not too far to walk to the centre of the campus where there were students standing around in front of what appeared to be the headquarters, but it proved to be quite difficult to find anyone who spoke much English, or at any rate, was willing to. In the end I found the best people to ask about the bus were the black African students, who probably spoke English at home,. Buses were coming all the time, and apparently I needed number 2, which turned out to be the same as the one I had come on. It was crowded and I had to stand most of the way.

The impression I got was that the NEU works on a straightforward basis “You give me some money, I will give you an education.” The fees for most courses are about 5000eu. per annum, apart from medicine and dentistry, which are much higher. Looking at the students I got the feeling that they were mainly from fairly well-off families. The NEU is a Muslim institution as might be expected, but there was no sign of any radicalism. Some of the female students wore head-scarves, but I did not see any with veils. Despite the warm weather none of the male students wore shorts, whereas in Britain or the USA most would have done. The only shorts in view were mine, and that is not a particularly pretty sight.

Back at Kyrenia Gate I left the bus and walked through the back streets to the Ledra Street check point, passing some run down workshops in which people were patching up old cars. There was nothing greatly of interest apart from two or three damaged rotary-engined Mazda RX8s, which I suspect would eventually emerge as one vehicle.

After another brief passport check I was back on the Greek side, aiming for the Cyprus Classic Motorcycle Museum, which is also in the back streets not far from the check point. This museum is the property of Andreas Nicolaou

and has about 100 machines on display. Andreas told me his family lived in Famagusta when he was young and they had a collection of 15 motorcycles, mostly British. When the Turks invaded they had to leave in a hurry and could not take the bikes with them. He thinks some of them might have finished up in England years later, bought by dealers who went to Northern Cyprus. Anyway, his family were successful in their new life in the South and he now has a total collection of over 400 bikes.

In the museum I got talking to a man who was in the British army and retired to live in Cyprus. I mentioned that I had been through the border, and he said “What! You’ve been through? I’ve never been!”. It was as if I said I had just been to Syria or Afghanistan. He also said that the U.N. Peacekeeping force along the Green Line was currently made up of British and Argentine soldiers.

The next morning I checked out of the hotel but left the car in the car park. The plan was to have another look round Turkish North Nicosia before driving back to Larnaca. I passed through the Ledra Street checkpoint again and turned immediately left inside the Green Line border and followed it round until I came to the city wall, where there was an area of no-man’s land with an

unoccupied U.N. watchtower in it. This area was rather run down but undergoing a large scale renovation scheme by the local authority and the U.N. From here I followed the city wall round to Kyrenia Gate and crossed over the ‘Ring Road’ into a tidy area of houses and businesses. After a while I came back to the Gate and walked all along the inside of the eastern city wall until I came to the Green Line border with its notices forbidding photographs. Turning right eventually brought me into the enormous bazaar and ultimately to Girne Caddesi which was about 100 yards from the Ledra Street checkpoint.

Before going through the checkpoint I had a cup of gourmet coffee at a street stall run by a man who had lived in Islington for several years. He was not particularly friendly, but his young assistant was, and started chatting to me in excellent English which he said he had taught himself. He said he was Kurdish, with a Turkish passport, and was studying psychology at the NEU. It was clear that he was very intelligent, but seemed to have little idea what the future held for him. I mentioned that I had difficulty in finding anyone who spoke English in the university, and he said “They can’t be bothered to learn”.

Back to Larnaca

After collecting the car from the hotel I set off on the motorway to Larnaca, turning off on the way to look at a place called Aradippou. The Elysso Hotel found a room for me, and I spent the evening walking down to the beach restaurants for a meal.

My return flight to England to England was not until the next evening, so I had most of a day to have another look at Larnaca. It was still my intention to try the electric scooters, so I parked near the Fishing Shelter again and walked down to the ebike hire place, only to find no one there and the bikes chained up. However, as I walked towards the town I came across some ordinary bikes for hire at the kerbside and got one of those for the rest of the day for 5 euros, a good rate for quite a good bike.

It enabled me to have another look at the old town and then go to some of the big shops further out on the main road towards Nicosia. There were a couple of hypermarkets with everything from stuffed toys to generators and workshop machinery, mostly with Chinese brand names unknown to me. Also an enormous HINO, DAF, SSang Yong, Suzuki dealership with vehicles that you would never find in one place in England.

After seven days of almost perfect sunshine in Cyprus it was a bit of an anti-climax as I trudged at midnight through the pouring rain in the near-flooded Long Stay North car park at Gatwick. I could not help feeling slightly envious of those people who would be having breakfast in the Tea for Two in Pathos in a few hours’ time.

Finland 2019

Finland 2019

CLICK ON PICTURES TO ENLARGE

The Finns are mad about cars and mad about museums, so it might be expected that they would be mad about car museums. And they are. During my research for this trip I found records of at least 20 transport museums in Finland, and that is for a population of 5.5 million, less than one tenth of that of Britain. The total time I would be in Finland was five days, which would limit the distance I could travel from Helsinki, and at the beginning of September some places were only open weekends or closed altogether for the winter. Eventually I whittled it down to a list of six good museums that I would be able to get to, and even then it would mean quite a bit of travelling. .

The Finns are mad about cars and mad about museums, so it might be expected that they would be mad about car museums. And they are. During my research for this trip I found records of at least 20 transport museums in Finland, and that is for a population of 5.5 million, less than one tenth of that of Britain. The total time I would be in Finland was five days, which would limit the distance I could travel from Helsinki, and at the beginning of September some places were only open weekends or closed altogether for the winter. Eventually I whittled it down to a list of six good museums that I would be able to get to, and even then it would mean quite a bit of travelling. .

It would be my second visit to Finland, the first being a day trip to Helsinki from Tallinn in Estonia in 2008, reported elsewhere on this site. This time I flew directly from Gatwick with Norwegian, and everything went well until we got off the plane in Helsinki. After walking a very long way we came into the arrivals hall to find a considerable queue which appeared not to be moving at all. Apparently the automatic passport-reading machines had broken down and the few officials present were standing around hoping that they would start working again. After about 15 minutes with an ever-lengthening queue they resorted to good old-fashioned manual processing, and even then they did not exactly rush their backsides off to get people through. Welcome to state-of the art super-efficient Finland.

After a well-organised handover of my Opel Astra from Alamo (the car hire firm, not Texas) I drove to the Hotel AVA in the suburbs of Helsinki. The Finnish capital is considerably further north than my home in England, and I thought it might be colder, but it was more or less the same and remained mild throughout my stay. The area around the hotel might be described as a leafy suburb that could be found in most big cities in Europe, with the exception of one side street which was distinctly Scandinavian in character.

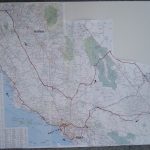

The next morning I set off for Espoo Car Museum. Espoo is a town about 12 miles from Helsinki and the museum is north of the centre near a lake. It could hardly not be near a lake because everywhere in Finland is near a lake, the country is totally peppered with them. By one standard of measurement there are 187,888 of them. Southern Finland has few hills of any height because there isn’t enough room for them between the lakes.

The museum opened at 11.00am and I arrived at 10.30, so I had to wait in a nearby field which was empty apart from a man standing by an immaculate Volvo ‘Amazon’ classic car. Unusually he did not speak much English.

The language

With native English, fluent German and a fair knowledge of French words (though not how to pronounce them or put them together) I can get by in many European countries, but Finnish is very difficult to read or understand when heard. I told one local man that I could not remember Finnish place names, and he said “Neither can we!” Fortunately most people in Finland speak English, usually extremely well. Most public notices are in Finnish and Swedish, often also in English, but surprisingly some of the museums had little in the way of description apart from Finnish.

The museum was oustandingly good, and run by very nice people, as most car museums are. An astonishing collection of cars, motorcycles, mopeds, bicycles and a huge amount of automobilia. A considerable proportion of the exhibits were from eastern Europe and as I left the lady in reception gave me a book about the history of the museum. When I drove away there must have been about 70 Volvo Amazons in the adjacent field, with more still arriving. It was Saturday and an example of the strength of the classic car movement in Finland.

To Kangasala

The two museums at Kangasala were about 100miles from Espoo and I cut across to the E12 motorway towards Tampere and then turned off at Hämeenlinna towards Kangasala. The motorway was quite busy at times and there was some rain, but the driving was generally good, as I had expected it to be. The scenery was pleasant enough, though monotonous as motorways often are.

The two museums at Kangasala were about 100miles from Espoo and I cut across to the E12 motorway towards Tampere and then turned off at Hämeenlinna towards Kangasala. The motorway was quite busy at times and there was some rain, but the driving was generally good, as I had expected it to be. The scenery was pleasant enough, though monotonous as motorways often are.

It was very much back into lake country, and the two museums were not far apart, more or less at opposite ends of a causeway over a lake.

Mobilia Museum

Mobilia closed much earlier than Vehonieme, so I went there first. This was an extremely smart museum, in which you could quite safely eat off the floor instead of the tables in the excellent restaurant should you wish to do so. It had a general section of cars and motorcycles plus a large rally car display, as rallying has a big following in Finland. All the exhibits were immaculate and everything was perfect. There were simulators and educational features that were clearly aimed at families rather than people who enjoy getting their hands dirty.

Vehonieme Car Museum

Smaller than the previous two, this museum is attached to a café and gift shop and is run by a family with a very long history of involvement with old vehicles. There are some interesting

exhibits and plans for expansion in the future. They also make special short-run 1:43 scale models.

Nokia

As the next stage would be 93 miles I had booked to stay the night at the Hotelli Iisoppi in the centre of a town with a very famous name - Nokia. It appeared to be more like

a pub with rooms than a hotel, and to be fair it did say on the reservation form ‘Please note that you might experience some noise from the on-site night club during weekends’. The price was reasonable and there were few if any alternatives in the area anyway. Fortunately after my many visits to American motels I always have ear plugs with me, and I certainly needed them. The noise started at 11.00pm and went on until 4.00am.

In the evening I had a walk around Nokia, which is a fairly characterless industrial town. The company of that name still has connections in the town but its headquarters are in Espoo and it has operations all over the world. Despite recent setbacks it is still by far the largest Finnish company.

The next morning I set off for the Uudenkaupungin Automuseo at Uusikkaupunki, so I knew I was definitely in Finland. This was a more scenic route over main roads with little traffic most of the time, despite which the road was being upgraded to dual carriageway for a distance of about 50 miles. In Britain we would think the existing road was more than adequate. There was a vast number of speed cameras, almost of them being recognized by my satnav and in any case I was not driving very fast. Police patrol cars seemed to be non-existent.

A feature of all country roads in Finland is the elk sign, which appears at frequent intervals on the roadside verge. Many years ago the Finns invented the elk test, a swerveability test for cars made famous by the incident in which an original A Series Mercedes fell over containing several journalists, but hitting an elk is definitely something to be avoided. I saw a large number of signs but no elk.

Uudenkaupungin Car Museum

Uusikaupunki is a small place on the west coast and home of another large company called Valmet as well as the museum. Valmet employs about 6000 people, engaged in sub-contract vehicle development and manufacture for Mercedes-Benz, Porsche, Ford, Opel and in the past Saab together with several other firms.

Adjacent to the factory is the Uudenkaupungin museum, which is divided into three sections. The first is a general car and motorcycle collection of a high standard. Then there is the Saab hall, with about 40 cars covering everything from the original 92 through to the GM based models, including a considerable number of rally cars and three Sonnetts. Finally there is a hall for other vehicles and engines made by Valmet. These include an early hybrid electric car called the Fisker Karma made for an American rival to Tesla. About 2000 were produced by Valmet. Also on show is a one-off concept car in the form of a 6-door stretched Talbot Horizon called the Horizonzon, so somebody in the company has a sense of humour. At the time of my visit I was the only person looking round.

Turku

From Valmet I followed the roads close to the coast down to Turku, a large town, noted for its attractive river frontage, harbour and castle. Because I was not sure how my schedule would go I had not booked a hotel in advance, but had noted details of one that looked suitable.

The street that the hotel was in was easy to find but very long, with the number of the hotel at the far end. As I approached the place where it was supposed to be I realized that this was not the best part of town, practically every building having the word SEX on it in some form or other.

Few of the buildings were numbered and I could not locate the hotel, so I parked and walked around to look for it. The street opened up into a square with a big hotel called Helmi on the right hand side, so I decided to see if they had any rooms, which they did but at a higher price than I wanted to pay.

After wandering about for a while and not finding any alternative I threw caution to the winds, booked into the Helmi and went out to find a restaurant. About 50 yards away was a Hesburger, the Finnish rival to McDonalds which can be found at frequent intervals in every town. I always say you can judge the quality of local cuisine anywhere by the number of McDonalds, and in Finland McDonalds have been firmly trounced by Hesburger, which must say something. Anyway, as it was raining hard I went to the Red Chopsticks facing my room at the back of the hotel.

The list of car museums included one called TS Auto Museum on an industrial estate on the north side of Turku, so that was my target the next morning. When I got to the address it appeared to be a derelict factory, and I was sitting in the empty car park deciding what to do when I realised that the Vikings had landed, or at least one of them had. Standing about 50 yards away was a tall young man with light ginger hair and a beard. He was wearing work clothes with an array of mechanic's tools on a belt round his waist. When I asked him if he spoke English he said "A little", but then, as I recollect from school history lessons, on their first visit to England they didn't bother much about languages. They just ran around waving axes and snatched our women. Anyway, he spoke enough to assure me that the car museum had definitely gone.

On the opposite side of the road was a warehouse-type building with several names on it, including MOTONET. It appeared to be something like a larger version of Halfords, and I thought it might be interesting. Within a short time of passing through the door I realised that this was THE BEST SHOP IN THE WORLD. It was not for the man I really am, but for the man I would like to be.

It had everything to do with action, adventure, and the great outdoors, surpassing anything I had seen in the USA, Canada, or anywhere else. Loads of car, motorcycle, huntin,', shootin', fishin' as well as mundane DIY stuff.

Bending down sorting things on the bottom shelf was a young lady with long blonde hair flowing over her shoulders. I asked her where to find something, and she told me in excellent English. She then stood up to her full height of about 6ft 2 in. Was she the sister or wife of the man in the car park? This shop had everything a man could hope for, but in my case, at 81 years old and 5ft 7in, I didn't think I was in with much of a chance.

As I had plenty of time I went back into Turku and parked near the river,

As I had plenty of time I went back into Turku and parked near the river, close to the entrance to a marine attraction called Forum Marinum, a riverside museum partly indoors and partly open-air. One of the main features was a large sailing ship undergoing restoration, although it looked pretty immaculate to me. For a short distance I walked along the quayside towards the town centre and came across some tiny bronze figures firmly attached to the concrete. There was no explanation for them.

close to the entrance to a marine attraction called Forum Marinum, a riverside museum partly indoors and partly open-air. One of the main features was a large sailing ship undergoing restoration, although it looked pretty immaculate to me. For a short distance I walked along the quayside towards the town centre and came across some tiny bronze figures firmly attached to the concrete. There was no explanation for them.

A path parallel to the river in the opposite direction led to the castle, which was closed on that day. It was an extremely Nordic structure, like three narrow towers joined together facing a courtyard with white buildings along both sides.

A path parallel to the river in the opposite direction led to the castle, which was closed on that day. It was an extremely Nordic structure, like three narrow towers joined together facing a courtyard with white buildings along both sides.

I think there was much more to Turku than I saw, but it was time to move on because I had to get to Lahti, a city about 144 miles away, the other side of Helsinki. It was an unpleasant motorway journey,with heavy traffic for a long way round Helsinki, and maybe it would have been better if I had cut across country. On the approach to Lahti there were many out-of-town shops and a fair amount of industry. Again, I did not have a hotel reserved, but had one noted down called the GreenStar and came across it quite by accident on the way into the centre.

Once sorted, I walked into the centre for a meal and look round. Lahti is the regional capital and has a rather unusual coat of arms in the form of a train wheel surrounded by flames. This may be because in the 1870s it was an important railway terminal and was almost totally destroyed by fire in 1877. Or perhaps the Finns just think up coats of arms like that during the long cold winters.

The city is situated at the end of Finland’s second largest lake with a bay that reaches almost into the centre. The lake itself has about 1900 islands, and is linked to the main streets by a park with fountains and a pleasant market square. Towering above the suburbs is the ski jump, which has been used for world championships.

Suomen Moottoripyörämuseo

The reason for going to Lahti was the Finnish Motorcycle Museum which I visited the next morning and was greeted by the friendly owner who had just returned from the annual Ace Café event in Brighton. His museum is affiliated to the Ace Café in London and has an excellent collection of motorcycles from all over Europe and America. In an adjacent building were about 40 motorcycles that he had recently bought from another collector in Finland, and he let me wander around in there. ‘About 40’ was the right description, because a large proportion of them were dismantled and spread around on the floor. He also had a London Routemaster bus for bringing people from the town in the summer.

It was time to go to the airport for my return flight home. On the way I stopped at a big shopping centre for a snack and a look round IKEA, which unsurprisingly was just like the ones in England.

Filling the car with fuel and returning it to Alamo turned into a nightmare, because although I had detailed instructions I got hopelessly lost in the airport, which is amazingly large. It seems to be quite modern, with two terminal buildings joined end-to-end, but I thought it was very poorly designed. It entails a large amount of walking at the end of which you still have to get on a bus to the plane. Gatwick might be dreadful, but at least the long walks usually take you right to the plane. Also, the seating arrangements in the departure lounge were poor, with too few seats, and those were like badly shaped hard benches. How this can be in a country which is famed for its furniture designs I do not know.

In four complete days I visited five museums and drove 600 miles, so I did not have a lot of time for general tourist activities, but I was rather disappointed with the architecture that I saw. Helsinki has many beautiful buildings old and new, but elsewhere a large proportion of buildings are just rectangular blocks with, to my mind, no architectural merit.

To anyone coming from pre-Brexit Britain Finland is incredibly expensive, many things costing at least fifty per cent more than at home. One favourable aspect is that virtually everyone is friendly and welcoming.

Belarus 2019

CLICK ON PICTURES TO ENLARGE

Belarus 2019

Not many British people go to Belarus. There are no cheap air fares and it is not noted for beautiful scenery, good climate or any other particular attractions. It was part of the Soviet Union until 1991, and is considered to have retained many of the trappings of its Communist past. Essentially a single-party state, it has had the same leader since 1994 and is often regarded as Europe’s last dictatorship. The lack of democratic process and retention of the death penalty are frowned upon by the EU.

Not many British people go to Belarus. There are no cheap air fares and it is not noted for beautiful scenery, good climate or any other particular attractions. It was part of the Soviet Union until 1991, and is considered to have retained many of the trappings of its Communist past. Essentially a single-party state, it has had the same leader since 1994 and is often regarded as Europe’s last dictatorship. The lack of democratic process and retention of the death penalty are frowned upon by the EU.

Until recently visitors from the Western world were deterred by the requirement for a visa which involved the same convoluted procedure as for Russia, but since 2018 it has become easier and at the time of my visit citizens of the EU and many other countries could stay for 30 days without a visa as long as they entered and departed via Minsk Airport. It was still necessary to register with the authorities within five days of arrival, but that would normally be done by your hotel, if you were staying in one. The entry requirements appear to be getting easier all the time.

There were various sources of information about Belarus on the internet, but only one proper dedicated guide book in English, published by Bradt, a company which specialises in guides to less popular destinations. The one for Belarus is really excellent, written by a British man with a long-standing association with the country.

The British Foreign Office provides quite a lot of advice for visitors, including:

Medical insurance is essential, because medical services are of a lower standard than in Britain.

There is little crime, but you should be vigilant against pickpockets etc.

Don't take photographs of government buildings, military installations or officials in uniform.

Don’t drink tap water without boiling first. Bottled water is advised.

Avoid consuming local produce in the area close to Chernobyl in Ukraine.

Main roads are generally in reasonable condition, but side roads are often very poor. Police check points on roads are common.

Jaywalking is regarded as a serious matter.

As always, my intention was to hire a car and drive around, finding hotels as I went apart from the first three nights, which were booked on the internet in advance. As I have driven in Russia and about 45 other countries I was not expecting the driving to be a problem, excepting possibly for the language.

Languages and finding the way

The official languages are Russian and Belarusian, which have equal status in law, although everyone can speak Russian whereas Belarusian is less widely spoken but gaining in popularity. The two languages are similar in many respects, both using the Cyrillic character set with slight differences, and they sound the same to most foreigners. English is taught in schools as a second language, but in practice, as I quickly discovered, few people can actually speak it and it almost never appears on road signs. There is generally little English or Latin script around other than for the names of businesses and products, such as McDonalds, Burger King, Skoda and BMW.

Before going I spent some time brushing up on my knowledge of the Cyrillic characters so that I could at least recognise place names on signs, because that is really essential if you are driving.

For route planning and navigation I had a paper map 1:750000 (approx.. 10 miles to 1 inch) with place names in English, HERE maps and MapsMe in my tablet, plus HERE maps in my phone. I also had my own TomTom into which I had put a map of Eastern Europe including Belarus, but that proved to be a problem, because it completely failed to recognise the place names as they were shown on the paper map. The only way round this was to scroll around the base map in the TomTom (which is possible on recent ones) until I found the place I wanted, write down the spelling and enter that on the TomTom keyboard.

Just to give an example of the situation as it applied to the name of one town.

Paper map: ASIPOVICY

HERE maps in tablet and phone: ASIPOVITSKI

TomTom: OSIPOVICHI

Roadside signs: АCІПОВІЧЫ

Obviously the roadside signs are the most important and that is why it is essential to learn the Cyrillic characters. You could say that a similar situation applies in countries like Japan, Taiwan, Greece, Georgia, Israel and Morocco, but at least in those countries main roads are often signposted in English as well as the local language, whereas in Belarus they are not.

Unexpected perfection

In view of the foregoing I had very little idea what to expect when I arrived in Minsk. The flight was three hours from Gatwick with Belavia, the Belarusian national airline, in a Brazilian-built Embraer 195 which looked as if had just left the factory. The food was not entirely to my taste, but otherwise everything was very good and few of the 100 or so seats were unoccupied.

At immigration I was asked for proof of medical insurance, although I am fairly sure that the officer could not read the documents, and she wanted to know where I was staying. The next thing was to get some Belarusian roubles, because as the rouble is a closed currency it cannot be bought or sold outside the country. Of the three bank counters at the airport, only one was open when I arrived, but I was quickly able to get some cash in exchange for GBP.

The first night was to be at the Green Park Hotel about 5 miles from the airport, and the driver of the hotel minibus, which looked as if it had just left the factory, was waiting for me in the arrivals hall. Ideally I would have picked up my hire car straight away, but all the hire car desks closed at 7pm and the plane came in at 7.15.

The hotel was modern and had extremely few guests, but was able to produce a meal for me,which was fortunate because there was nowhere else for miles around. The next morning the minibus took me back to the airport to get the car, a Skoda Rapid (Hockey Model!), which was perfect with 2000km on the clock and looked as if it had just left the factory.

All this perfection was a considerable surprise, because I had expected Belarus to be rather run down. At the airport I had my first and only contact with the police when they came alongside and told me to move on while I was setting up my satnav. They were less aggressive than the ones in Georgia.

Slightly off the beaten track

As always, I was hoping to find some classic car museums, and had the details of one in a folk museum in a place called Dudutki that I could get to on the way to Minsk, which is about 25 miles from the airport.

Everything went well to start with. The TomTom took me on well-surfaced main roads with little traffic for a long way and then a few miles on a motorway with astonishingly heavy traffic, apparently coming out of Minsk on the Saturday morning. After a while it directed me to take another single carriageway and then told me to turn left on to a wide gravel road through a village. This went on for two or three miles, and just as I was beginning to wonder whether it was right it turned back into tarmac for some distance until it came to junction of three gravel roads. It told me to take the one straight ahead, which was clearly in a very bad state and not passable with an ordinary car.

I looked at the map in the tablet and saw that I was on the edge of a fine network of roads which were obviously a settlement of some sort and it was only about a mile to the main road that went past Dudutki. If I turned right it appeared that I could get through the network to that road.

The roads in the network were actually narrow grass tracks running between plots of land with dachas (detached houses, usually made of wood) on them. In Russia it has long been the custom for city dwellers to have such houses in the countryside to which they can retreat in the summer and it seemed that I had stumbled across a large complex of similar properties in Belarus. For some distance I carried on along the track, which was very bumpy and only about ten feet wide until it turned right again, still running past houses with no one in sight to ask for directions.

At last, signs of life. On the left hand side of the track a man was shovelling straw. When I pulled alongside him he looked at me, smiled with his two or three teeth, and it was immediately clear that there was no possibility of meaningful conversation. I continued lurching slowly along past several overgrown junctions for a while, and then saw that the road was dwindling away to nothing not far ahead.

I just sat there wondering how on earth, within an hour of leaving the airport, I had finished up in this predicament. On the map in my tablet I could see where I was, but it was impossible to know which of the vast network of narrow rough tracks made up a viable route to the outside world.

The only immediate course of action was to reverse about 300 yards until I came to a junction with a track that appeared to be clear for some distance. It was difficult even to get into it, but just as I did a sane-looking man appeared from a garden. When I asked him if he spoke English he shook his head and said “Deutsch”? I changed to German, but his knowledge of that language was no better than his English. He went into his garden and came back with a young man of about 20, presumably his son, pointed to him and said “English”. The lad said “Little” and it quickly

became apparent that that was indeed the case. However, I showed them the map on my tablet and where I wanted to go. The older man said “Google maps?” Now we were getting somewhere. They took the tablet and were obviously familiar with such things. The lad pointed along the track, said “Forest” and indicated that I should turn right at the forest. He then showed me which roads to take on the map, and I eventually got through to the main road and Dudutki with the car unscathed, rather surprisingly.

The folk museum was firmly aimed at family entertainment as well as education, with several coaches and a good number of cars in the car park. There were lots of animals and birds with workshops and displays of traditional country crafts. The classic vehicle section was small, involving mainly cars from the Soviet era as I expected, and not really worth the foregoing trauma.

Minsk

It was time to push on into Minsk, a city of 2 million people, which the TomTom managed to find without too much trouble. From what I had read I was under the impression that the streets of Minsk had little traffic, but that was certainly not the case. It was late Saturday afternoon and quite busy, although there were no real traffic jams. The standard of driving was very much better than I expected and certainly better than in most west European capital cities.

Unusually, I had booked one of the better hotels in town with the inspiring name of Belarus Hotel, a 23-storey skyscraper on high ground, which made it very easy to find. It had an excellent guarded car park into which I was allowed without question, contrary to my experience in Russia.

Luckily I just managed to beat a coach party to the reception desk, and was given a good room on the 7th floor with a wide open view that could

best be described as surreal. The hotel was effectively in a park with a river running through it, and along one side were white-painted buildings in what might be seen as a Flemish style. On the other side of the park were mostly modern buildings, including a couple with big bright screens on them showing advertisements. This was not at all what I had expected in Belarus.

Once sorted I walked down to the city centre to get something to eat. It was a lively Saturday evening scene, with many young people enjoying themselves seemingly oblivious to the dictatorship or the death penalty. Apart from the ones who had moved me on at the airport I don’t think I had seen any police. Nevertheless, I was careful to stand in line with everyone else at the pedestrian crossings until the green man came on, and absolutely no one jaywalked. Perhaps that is where the death penalty comes in.

After a wander round and a meal at a well-known American fast food place (shocking!) I returned to the Belarus Hotel and took the opportunity to climb to the higher floors and take in the expansive view across the city in all directions.

Some of the most prominent buildings within easy walking distance of the hotel were the Great Patriotic War Museum and the nearby Triumphant Arch in Victory Park, both listed as top sights for visitors, so that is where I aimed for after breakfast the next morning. Belarus suffered dreadfully from the advance of the Germans into Russia and their subsequent forced retreat in World War II, known locally as the Great Patriotic War, with appalling atrocities resulting in the death of one third of the population. Every town and village has its war memorial, often in the form of abandoned tanks or field guns, and there are said to be over 9000 monuments dedicated to the tragic events.

On the way across the park I was astonished to find three “dockless” electric scooters of the type that have been in the news for causing problems in recent times in Los Angeles, Paris and many other cities around the world. They are illegal in Britain at the time of writing and I had never seen them before. They were standing with practically no one in sight, just waiting for someone to come along and hire them using a smartphone. I fiddled about trying to make them go, with no success, and resolved to find someone who could explain how the use them if the opportunity arose.

I took some photos of the Arch and went on to the museum, where a lot of soldiers were waiting outside, presumably intending to visit. Bearing in mind that Belarus (as Bylorrussia) was part of the USSR at the time it is not surprising that the majority of the tanks, weapons, planes and other exhibits were Russian, and everything was labelled in that language. There are several halls with a vast number of exhibits, including recreations of battle scenes to help to bring home the horrors of the event and also sections containing records and documentation. Adjoining the

museum building is the spectacular Minsk Hero City sculpture consisting of a 45m high stainless steel obelisk surrounded by eleven sparkling ‘rays’ to represent the 1100 days of occupation during the war.

On leaving the museum I discovered a surprising concession to tourism in the form of a row of ‘fun vehicles’ on a large paved area. Among them were the aforementioned electric scooters, some strange fat-tyred scooters, Segways and quad bikes, all electric and made in China. All these manifestations of the Devil would be totally illegal on public land in Britain, but in Minsk they could be hired by anyone over a certain age. Needless to say I could

not resist trying one of the fat-tyred machines at about £2 for five minutes. The man in charge did not ask my age and there were no checks for sanity. During my demonstration ride I was watched by about 30 soldiers who amazingly did not jeer, but perhaps there was an officer present.

As I set off to walk into the town the soldiers went past in a long line, so I tacked onto the end while they were waiting to cross the road, just to get a feel for being in the Belarusian army.

On the way into town I was just passing a multi-storey shopping mall that would have been considered smart by any standards when two men and a woman all aged about 30 came sweeping up on the little electric scooters and stopped in front of me. I heard one of the men speak, and I said “Oh, do you speak English”. He said “Yeah mate, we’re Australian”. I said “Well, perhaps you could show me how to use these things”. “Yeah mate, they’re great, we use ‘em everywhere”. They explained how to register by pointing your smartphone at a QR code on the handlebars and putting in your bank details, which enables you to unlock the scooter. However, as I have only very limited data in my phone and was not very happy about putting in my bank details in the street in the middle of Minsk I decided to give it a miss for the moment.

In the shopping mall a friendly German who lived in Minsk helped me to buy a coffee and a strawberry cake, after which I continued exploring the city. Minsk was virtually totally destroyed during the war and the central area was rebuilt to a high standard with good quality buildings. There is a recommended walking route that takes in most of the sights, starting at the very modern railway station which you are not supposed to take photographs of, but I did. I managed to get a tourist map and covered as much ground as my knee would allow.

The city is very much better than I expected. I thought it would be a gloomy, lifeless place, a relic of the Soviet Union, instead of which it seems to be thriving with most of the attractions and distractions of a West European city. The traffic density is probably about one third of that in Britain, reflecting the lower level of car ownership, so speeds are often higher, but not to an extent that I would regard as dangerous. Most of the vehicles are modern and in good condition (though that is not so once you get out into the countryside).

Running through the middle of the city is the river Svislach, the one I could see from the Belarus Hotel, with areas of parkland along its banks. It varies greatly in width but is generally not wide or deep enough to carry large vessels.

The route took me past many distinctive buildings including the Red Church, the Greek-style Trade Union Cultural Centre and the KGB headquarters, which you are also not supposed to photograph. There are plenty of pictures on Google Images and similar. Whereas in Russia the KGB has been replaced by the somewhat less formidable FSB, in Belarus it is still the KGB.

From the imposing State Circus building I turned westwards into the “old town”, a reconstructed area with a pedestrianised main street lined with cafes and restaurants forming the centre of night life in the city.

One thing about Belarus that is noticeable to anyone coming from twenty-first century Britain is the almost total lack of diversity. During a whole day in Minsk I saw only a few people of a different racial type from myself (“white Caucasian”). Like western Russians, Belarusians are generally quite large and I noticed a surprising number of tall women.

In the course of my advance planning for the trip I had found references to five vehicle museums including the one at Dudutski. Three of the remaining four were in Minsk, at the tractor factory, the motorcycle factory, and a small collection at the Ministry of Internal Affairs Museum. The largest collection in the country was supposed be at a village called Slipki about 50 miles north of the capital and the description on automuseums.info included a map showing the exact position of the museum in the village.

A day of wild goose chases

The next morning I set off for Slipki on the P58 main road to the north. Once clear of Minsk the traffic was light and the road well surfaced, running through pleasant but not exceptional countryside. The TomTom took me through a place called Illya (or Ilya) where I stopped to look at the market and bought a T-shirt with thin blue and white horizontal stripes like the ones Russian soldiers wear under their uniforms. The man on the stall looked me over to assess my size and selected one that ultimately turned out to be about four sizes too large, but at least I could say “Been there, done that and bought the T-shirt”.

Some distance after Illya I noticed a village on the left with its main street running parallel to the P58, and turned off to look at it. It was exactly like some I came across in Russia, with a dirt surface and no signs of life apart from a small dog standing in the middle of the road. It reluctantly moved out of the way as I approached. The houses were typical wooden dachas, some in good condition but others in a total state of dilapidation. I drove the whole way through the village and back without seeing any living creatures apart from the dog. There was nothing to show that many of the properties were occupied.

A short distance after I rejoined the P58 the road crossed a lake via a long causeway and bridge. The lake was shown on my map as Viliejskaje Vdsch, which defeats Google Translate, but appears to mean Lake Viliejka, after the adjacent city of that name. This is the only lake I saw in Belarus and they are few and far between. A few mile further on the satnav indicated that I should turn left on to a rough road for about three miles to Slipki, where I stopped to get my bearings. The layout of the narrow streets seemed to correspond to those on the map with the museum information, so I followed the route through the village to the point where the map showed a turning off to the right to the museum. There was a junction there, but it was an extremely rough track, impassable for a car like mine without risking some damage.

I went back into Slipki to see if I could find someone who might be able to help, and saw a well-worn car pull into the garden of a dacha. A couple got out and I approached them with the map and picture. They were both about 40 and were willing to help but needless to say did not speak any English. They did not appear to have any knowledge of the museum but the man indicated that he would come with me in my car to try to find it. We retraced my drive through the village until we came to the junction with the rough track and the man agreed that it was the place shown on the map. All this was done somehow without a word of English.

He then took out an unbelievably battered smartphone with an almost opaque screen, dialled someone, spoke to them and handed the phone to me. The lady the other end spoke good English, and I told her what I was looking for . She said there was no museum in Slipki but there was one in another village about 40 miles away and she would explain to my friend how to find it. He took the phone and had a discussion with her. He then took my tablet with the map of the area and put a marker on the place the lady had mentioned. Like the man I met near Dudutki he seemed to be quite familiar with the device, actually more so than I am. I took him back to his house, thanked him, and decided to return to Minsk, as I did not want to do another 80 miles when there was no certainty that the museum would even have any vehicles.

It is quite interesting to consider this situation, because we were in an obscure village 50 miles from Minsk in a country that until very recently has received few foreigners apart from Russians, and yet this man seemed quite comfortable dealing with me. Most Belarusian men do national service which would bring them into contact with a wide range of people, but probably not foreigners. I regretted afterwards not trying to find out more about him, but the language was a problem. What did he do for a living? They had a large garden, but I doubt whether it was big enough for them to live from and there did not appear to be any industry in the area. When I met him it was in the middle of a weekday, when you might have expected him to be at work. Maybe he worked from home with his digital skills. From the state of his car and phone he cannot have been very prosperous.

In Ilia the market had gone, and I got some sandwiches from a shop to keep me going before driving on to Minsk and the hotel. It was still only about 4pm, so I walked to the Ministry of Internal Affairs museum in the city centre, which was open. I had a picture showing a number of old vehicles in the car park, but there was just one old police jeep.

I went into the building through the heavy glass door and was met by a man in uniform with a hat with a big round flat top. The diameter of the top of the hat of officials in this part of the world is an indication of the status of the wearer, and I would say that this one was actually medium on the scale of such things. By our standards they are slightly ridiculous and it is difficult (but essential) not to laugh. The man noted down my name from my passport and then followed me closely as I walked around pretending to be interested in lots of things. Predictably everything in the museum was in Russian and there was only one vehicle, a BMW police motorcycle. Eventually I departed without a word having been spoken.

It had not been a staggering successful day, but I had met a couple of characters that most people would not meet.

Factories

After a snack breakfast in the hotel café as opposed to the expensive and crowded restaurant in the morning I set off for the Minsk Tractor Works. There are not many products that Belarus is famous for but tractors is one of them and certainly one of the country’s best exports. For many years they have been sold throughout the world, including Britain, under the trade name Belarus. They are not considered to be on a par with John Deere or Massey Ferguson, but are considerably cheaper.

The tractor factory is in an imposing Soviet-style building alongside a

main road about three miles from the city centre. It has an area of well-kept parkland in front of it giving it a ‘garden city’ sort of look. A few tractors were dotted around among trees and hedges. The firm was founded in 1946, and the first edition of the company newspaper was said to be a true chronicle of analytically verified plans and programs, glorious patriotic achievements and the spiritually rich life of Belarusian tractor builders. They must have done something right, because by 2005 there were almost 20,000 workers.

The museum entrance was directly on the front of the building, and after paying 1.70 roubles for a nice ticket with pictures of old tractors on it I was sent through to another door where I was met by a serious-looking man who spoke no English. There were several areas containing pictures and many tractor-related items, but no actual tractors. All the documentation was in Russian. The man followed me round and on the way out I pointed to a closed door, which he promptly opened, revealing the boardroom.

I walked along to the main factory entrance doors which led into a hall with about twenty turnstiles, each with two cameras, one at waist height and one at face level, so it appears that they have an advanced security system which can link the wearer’s face to their pass barcode or photo. The other side of the turnstiles I could see lots of tractors, so I attempted to blag my way through with no success. The best response I got was “Perhaps tomorrow”, which appeared to be the sum total of the English of the staff present, but then, that is more than my Russian and it is difficult to blag if you have no common language with the other person. Some time afterwards I discovered that with one day’s notice I could have gone on a factory tour, but no one told me at the time. Bad planning on my part.

Having failed at the tractor works I decided to inflict myself on the motorcycle factory down the road. MINSK (now M1NSK) motorcycles commenced production as a state-owned business in 1951 and for many years managed to sell all over the world in the face of competition from the west and Japan. By 2007 they were struggling and passed into private ownership, their main markets now being Belarus and Vietnam. In addition to motorcycles up to 500cc they make bicycles, scooters, ATVs and snowmobiles.

Their main address and showroom is in a small building like a shop alongside the Soviet-style factory. The motorcycles are quite modern in some ways (styling, LED lighting), but a bit behind the times in others, and would probably not comply with current EU regulations. There was also a fully electric model and they are starting to sell some Chinese bikes. I had seen some pictures on the internet of some old machines that were supposed to be on display at the showroom, but no one in the shop could speak English or recognise the word ‘museum’.

The entrance to the assembly plant along the road was like something out of the 1950s, unlike the tractor factory, and there was clearly no chance of getting past the gatehouse. It had been another not very successful day, and I spent the evening with a meal and walkabout in the old town.

Moving on to Babruysk

By this time I had had a good look at Minsk and some of the surrounding country areas but I wanted to see another town. Originally I planned to go to Brest, which has a number of tourist attractions, but it is a border city and I felt that it was not really very typical of Belarus. After studying the map I decided that Babruysk, a town of about 215,000 inhabitants100 miles from Minsk would be a good place to go the next day. It only appeared to have two hotels and was clearly not tourist orientated.

The morning traffic on the motorway leading south east towards Babruysk was surprisingly heavy for about 15 miles until it split at a junction, after which it became quite a pleasant drive, bypassing the towns of Marjina Horka and Asipovicy (map spelling). The two hotels I had listed in Babruysk were the Yubieynaya on the approach to the town and the Hotel Tourist in the centre.

From the map it appeared that the Yubieynaya would be easier to find, have better parking and probably be cheaper than the Tourist. It was

extremely easy to find, as it was just off the main road leading from the motorway into the town, and had parking on a layby right in front of the entrance. The door led straight into a large wood-panelled hall with an unmanned reception desk with no papers or anything in sight. I waited for two or three minutes, and then someone walked past me and pointed out that the receptionist was sitting behind a small hatch at the far end of the room.

This was a far cry from the Belarus Hotel. A room was available on the third floor for about a third of the price that I had paid at the Belarus. The hotel was actually quite large, with nine floors and around 150 rooms, served by two tiny creaky lifts. On the way to my room I passed a couple of other people, but generally there did not seem to be much going on. The room itself was clean and quite well furnished, though perhaps a bit dated, the only shortcoming being that it was almost entirely pink. The view consisted of a large open area with roads running through it, carrying little traffic at that time of the day.

It was lunchtime, so I went down to the restaurant, which was empty. A lady came over and gave me a menu in Russian. It seemed that no other menu was available and no one spoke English, but somehow we decided that I should have soup and meat with rice. At this moment more guests appeared en masse in the form of a football team of boys in their early teens, together with four men who were apparently their trainers, teachers, etc.

Looking around at the pictures on the wall, it dawned upon me that this was a football themed hotel, used largely by visiting teams. Football is taken very seriously in Belarus and Belshina Bobruysk has had some championship success in the past. The boys were well-behaved and seemed to enjoy their meal rather more than I did, but I suppose it depends on what you are used to. Food is not one of the main subjects of my reports, and I am certainly not going to make an exception in the case of Belarus.

After the meal I went into the town centre by car and found a parking space with no difficulty. Far from being the run-down industrial town that I expected, it consisted of pleasant tree-lined avenues, all very clean, a little bit like Cheltenham. In the very centre was a park with the obligatory war memorial in the form of a T34 tank adjacent to a large paved area on which children were driving around in hired electric miniature cars (illegal in Britain). The surrounding streets were mostly pedestrianised, with small shops.